This Day in Labor History: October 4, 1971

On October 4, 1971, President Richard Nixon used the Taft-Hartley Act’s cool-down clauses to stop a longshoremen’s strike that was primarily over the response to containerization on ships. This strike demonstrated the continued power of the International Longshore and Warehouse Union, it’s strong democratic traditions, and how unions responded to the growing automation that cost many workers their jobs.

Longshoremen had been a center of American unionism for a long time. But the two major unions were extremely different. The International Longshoremen’s Association was dominant on the east coast and was also a mobbed up union that was exceptional corrupt. The International Longshore and Warehouse Union had formed in 1937 in the aftermath of the 1934 strike led by the Australian radical Harry Bridges. The ILWU developed strong democratic traditions under Bridges’ leadership, often in the face of extreme anti-communism that was used against it.

By the 1960s, the ILWU had a long tradition of winning good contracts on the west coast. But the shipping industry didn’t like this any more than other industry. Moreover, labor was a huge part of their costs. It took a lot of workers to load and unload a ship. So as technology advanced, new innovations developed that would save a lot of labor. That gave the docks a real opportunity to take power back. Containerization added to this. Simply put, having huge containers full of goods that could be loaded and unloaded with cranes saved a lot of money for the docks, the ships, and the consumer. It was going to be very hard for even the best union to resist this.

So the ILWU was in a tough spot. In 1960 and then again in 1966, the union agreed to what were called Mechanization and Modernization contracts, which took power away from the autonomous locals that controlled most of the work on the docks and even opened up possibilities for non-union members to get work. Moreover, one of the big wins workers had achieved was controlling the hiring hall, which had come after the long and exploitative history of using the shape-up to hire workers for the day. The 1960 contract was met with a lot of grumbling, but workers were really upset by the 1966 contract.

Now, Harry Bridges was a senior legend in the labor movement. But he was not the radical direct action guy of 1934. He was a bit out of touch with the rank and file by this time. He also did not see much hope in resisting in the containerization of the industry. He wanted the ILWU to save what they could and sign the next contract in 1971, despite the next round of cuts. But the workers were going to hold the line. And this was not the United Mine Workers, run in an autocratic union. It was a real democratic union. Bridges was the hero to many of the workers but they didn’t necessarily follow his every move. Many felt he was becoming too conservative and accommodating. So they rejected the contract and decided to go on strike. Bridges was pretty mad and so fought his own workers during the entire strike.

Shutting down west coast ports was a serious threat to the economy in an increasingly globalized world. Many industries depended on imports and exports to survive. So the ILWU strike worried both industry and the government. This was the first major strike in the industry since the epic 1934 struggle. Moreover, this had a military component to it, as the government generally used private industry to move supplies to Vietnam.

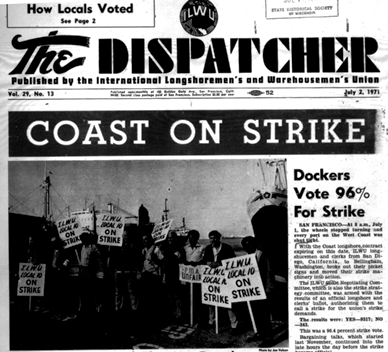

The strike started on July 1 and still had not ended on October 4 when Nixon used the Taft-Hartley Act to bring the parties together. One of the many terrible aspects of that law is the president can halt a strike and issue an 80 day “cooling off” period that requires workers to return to the job and mediation of some form to take place. They can return to the picket line after 80 days, so it’s not a full-fledged strikebusting power, but it’s pretty close to that. At the end of September, the strike moved to the east coast and the ILA joined it. That doubled up the reduction of shipping. This then became too much for the government to allow. Nixon issued the Taft-Hartley injunction on October 4 and it lasted until January 17, 1972.

So the ILWU and ILA went back on the job. Negotiations continued. But in the 80 days, there was no deal the workers would accept. In December, the workers were forced to vote on the same contract they had rejected in October. They rejected it by a mere 10,072 to 746. So as soon as the cooling-off period ended, they went back on the picket lines. This forced congressional action. In February 1972, Congress worked to pass legislation for compulsory arbitration. This passed on February 7. But on February 6, the ILWU and the dock employers came to a deal. And it was an interesting one. Basically, the deal was that the companies could slowly wind down the employment numbers of the docks. They weren’t going to give up on the profits of containerization. But in return, the workers would get a lot of money. And really, it was a very sweet financial deal. They gave a significant wage raise, new medical and dental programs that covered basically all the cost of prescription drugs. They got really lucrative pensions and a great life insurance package. Moreover, the retirement age with full pension was reduced from 69 years old with 25 years in the union to 65 years with 25 years in the union. Many did not see the strike as a victory at all. But it did lay the groundwork for the later years of the ILWU.

The ILWU remains a pretty militant union today. There can still be some significant tension on the docks, as there has been in Longview, Washington in recent years. They are still quite well paid. And their numbers continue to decline as automation plays an increasing role on the docks. But if your job begins to disappear, there’s a lot worse fates than at least making sure that you are going to get a lot of money and amazing benefits for as long as it lasts. These have become some of the very best working class jobs in the United States, even if there aren’t very many of them.

To read more about this, check out Peter Cole’s Dockworker Power: Race and Activism in Durban and the San Francisco Bay Area.

This is the 411th post in this series. Previous posts are archived here.