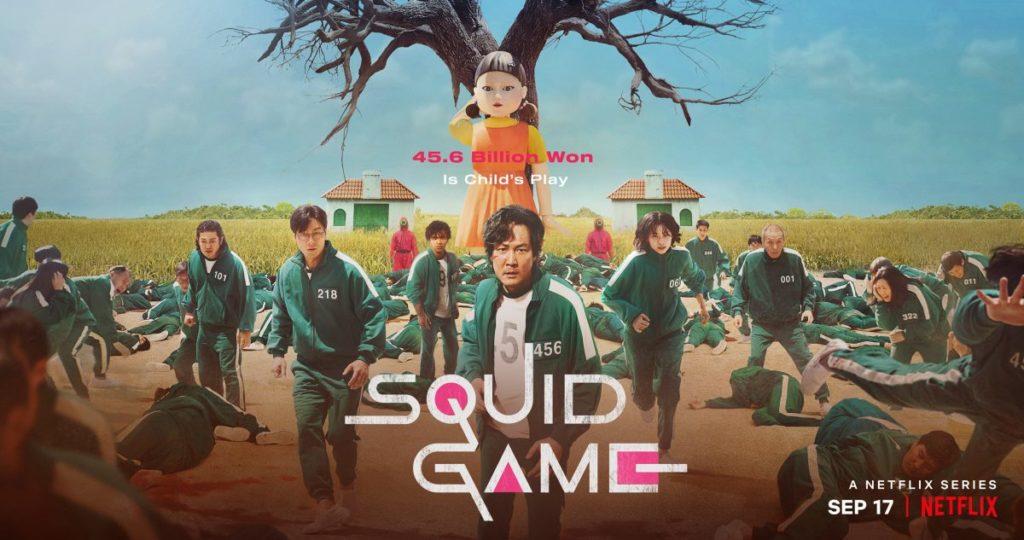

Squid Game

Isn’t it just the way? You wait all summer for a good Netflix series, and then two come along in the same week. No sooner had I finished enjoying Midnight Mass than a critical mass of praise began building on my twitter feed for Squid Game, a Korean show that is sort of a cross between Parasite and The Hunger Games. According to Netflix’s publicized viewing figures (which are, to be fair, not entirely reliable, but probably also not completely off-base) it’s already one of the streamer’s most popular offerings, but the level of discussion it’s received from English-language sites has so far been fairly minimal. I can’t help but feel that this has a lot to do with the foreign language barrier—if it weren’t for that, I firmly believe, Squid Game would be this year’s Queen’s Gambit: a clever, slickly-made, disturbingly fun show with compelling characters and—which is one better than the chess show—a core of interesting ideas.

Squid Game’s protagonist, Gi-Hun (Lee Jung-Jae), is a lovable dirtbag. A former factory worker, now unemployed, he’s deeply in debt to both the bank and loan sharks. He spends his days dodging the latter, cadging money off his equally impoverished mother, and trying to hit it big at the racetrack. He’s the sort of person who, as another character eventually observes, needs to “get into trouble to know that it is trouble.” He’s got no job prospects, no realistic chance of climbing out of debt, and no future. In this, as Parasite and many other recent works of Korean film, TV, and literature have argued, he is representative of a growing segment of their society, buried by rising inequality and limited opportunity.

Despite his many flaws, Gi-Hun is also reflexively kind and even childlike. It’s perhaps this last quality that attracts the attention of the organizers of the titular game. They approach Gi-Hun, promising money in exchange for playing children’s games, and before long he and 455 others have been whisked off to a secret compound, wearing matching tracksuits and policed by masked guards. The first game is Red Light, Green Light, but with a twist: when players are spotted moving during a red light, they’re gunned down with a sniper rifle.

This first game scene, in which panicked players are mowed down as they try to escape, while those who keep their cool just barely manage to cross the finish line in time, is at once harrowing and visually stunning. This sets the tone for the entire series, which is incredibly violent, but also hard to look away from, situating the broken, mangled bodies of the players in brightly colored, cheerful games arenas, and getting maximum mileage out of the inventive brutality with which one can turn these childhood pastimes into bloodsports. The show is full of bizarre and striking visual touches. When players are eliminated, their bodies are placed in coffins that look like gift boxes, complete with a pink ribbon. The guards who oversee the games are dressed in identical magenta coveralls, and their masks are emblazoned with geometric shapes that distinguish their jobs. As the number of players dwindle and the room they’ve been housed in is emptied of their cots, it’s revealed that its walls are decorated with stylized depictions of the games they’ve been tasked with playing.

There are six games in all (creator Hwang Dong-Hyuk does a good job of balancing games that are uniquely Korean with others that are played all over the world). Each one challenges the players in different ways, but also forces different social configurations between them. One game is played in teams, creating bonds of friendship and loyalty between the players. The next one forces them to play to the death against each other. A particularly vicious trial sends the players single file across a bridge where with each step, they have to choose between two tiles, one of which will shatter and plunge them to their deaths. The players at the back are thus motivated to urge the ones in front of them forward, so they can chart out a safe course, while the ones at the front try to force others to go ahead of them.

On their own, the game scenes would make Squid Game a riveting, pulse-pounding show (not unlike the chess scenes in The Queen’s Gambit). But what gives them extra flavor and importance is the reason the players are competing. After the Red Light, Green Light massacre, the surviving players are given a choice: they can vote to leave, in which case the prize money—one hundred million won for each fallen player—will be distributed among the dead’s relatives. If they keep playing, however, one of them has the chance to win the whole pot. (This did my head in while watching the show, so as a service to you I’ll mention that 1000 won ~ 1 dollar.) All but a handful choose to stay.

At first this seems purely like desperation, but eventually it becomes clear that in some ways, the game is better than the world outside it. It is, as its administrator insists to his underlings, “fair”. It’s incredibly, sadistically cruel, but at least there are clear-cut rules, and the consequences of both following and deviating from them are neatly laid out and immutable. And unlike the outside world, where people like Gi-Hun can never really win, despite all that they’ve been told to the contrary, here there is a guarantee that at least one player will come out ahead. To people down on their luck like the players in the game, the idea that you could gamble your life—and win a fortune—on a game of marbles or tug-of-war makes for a more comforting, more rational world than the one they’ve been living in, in which every choice has been a losing one, and the rules keep being changed and reinterpreted to their detriment. (This is also what distinguishes Squid Game from stories like The Hunger Games or Battle Royale. In those lethal games, beleaguered youths confronted the hostility of their elders with a fiery will to live. Squid Game‘s participants are mostly middle aged people, trying to turn their backs on the compromises and disappointments of adulthood and retreat to the simplistic rules that governed their childhood.)

To make this point, Hwang humanizes a large swathe of player characters besides his lead, each of whom has a different reason for choosing a fight to the death over ordinary life. Sang-Woo (Park Hae-Soo) is a childhood friend of Gi-Hun’s, the pride of their neighborhood for getting into university and landing a cushy investment firm job, who is about to be arrested for fraud. He initially forms an alliance with Gi-Hun, providing cool rationality to complement his friend’s bleeding heart. But eventually it becomes clear that he’s ruled by a monstrous sense of entitlement, a belief that he is fundamentally better than the other players despite being in the same straits as them. Sae-Byeok (Jung Hoyeon) is a Northern defector trying to put together the money to smuggle her mother out. She’s a canny operator who figures out how to manipulate the game sooner than anyone else, but her inability to trust others leaves her dangerously isolated. Ali (Anupam Tripathi) is a Pakistani guest worker whose boss has stolen his wages. Uneducated and perhaps trained in subservience, he automatically trusts Gi-Hun and Sang-Woo’s leadership, even when he probably shouldn’t. Over the course of the series they form complex, ever-shifting relationships as the demands of the game change the way they relate to one another. Though there are villains within the players’ ranks (chiefly Hae Sung-Tae as a gangster who has stolen money from his boss), most are depressingly ordinary, even as they betray each other and make increasingly untenable moral choices.

Ordinary, in fact, seems to have been Hwang’s byword in constructing his characters, often lingering on a player’s desperation and terror in the moments when they realize they’ve made a fatal mistake, finding a core of humanity in the middle of his heightened premise. Gi-Hun, meanwhile, grows more complex and layered as the game progresses, revealing not only decency and leadership qualities, but hints of his past that make it clear how far he’s fallen to his current, debauched form, and how that fall was really more of a push, by authorities and systems happy to immiserate people on behalf of the wealthy. It eventually becomes clear that almost every player in the game is struggling with trauma, not from the events of the game (though these certainly don’t help) but simply from living in the world.

The glimpses the show gives us of the game’s backstage area are more of a mixed bag. A subplot about a police officer who infiltrates the game (Wi Ha-Jun) is thrilling but ultimately goes nowhere. It’s important primarily for revealing that the people who make the game run are, in some ways, just as tightly controlled, and just as desperate, as the ones participating in it. The further one goes up the chain of command, however, the less essential the revelations the show offers feel. Squid Game’s conceit is so powerful and effective that it’s almost a bit of a letdown when we get a glimpse at the people for whose pleasure the whole thing is being staged. The show has, by that point, so successfully established the logic of the game and of people’s decision to participate in it that it doesn’t really feel necessary to pull back the curtain and reveal the villains behind it all. After all, the real villain isn’t some hedonistic billionaire looking to play the most dangerous game, but an entire economic and political system that has produced people desperate enough that they’re willing to be the prey.

It’s this fact, too, that renders Squid Game’s conclusion a bit wobbly. The season ends with an obvious hook for the next one, in which the game’s winner vows to hunt down its organizers. Which seems like the wrong target. On the other hand, the first season is so engrossing that it’s hard to complain about the possibility of getting another one, even if I’m skeptical that there’s a conclusion to this story that would truly satisfy. Until we get that, however, the show as it stands is nearly perfect, a sparkling confection with a dark, bitter center that more people should watch and talk about.