Historical Memory Priorities

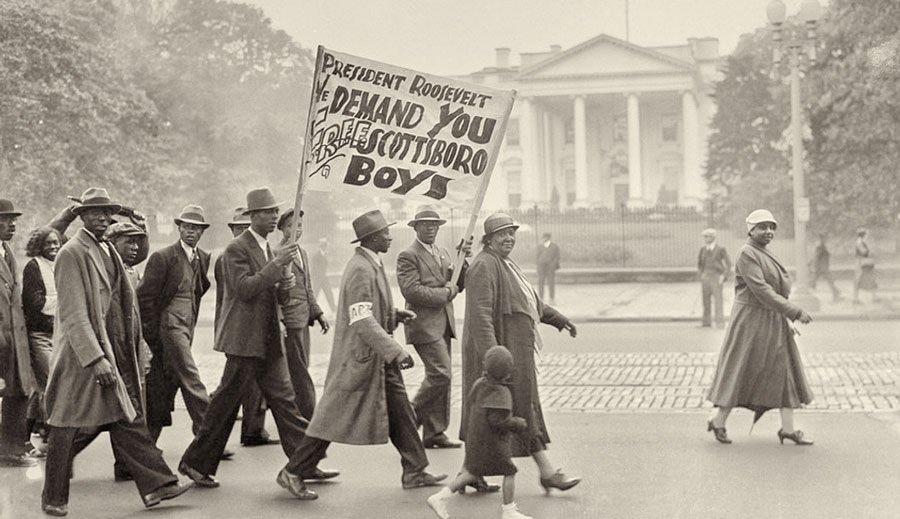

On Monday, I happened to be in Scottboro, Alabama, home of the Scottsboro Boys incident, where 9 innocent Black young men were nearly lynched in 1931 for supposedly raping two white girls. In fact, if there was sex, it was consensual, as often happened on trains during this period. The boys were searching for jobs. The girls were caught in the greatest taboo act possible and so used the rape excuse to gain respectability. The boys were nearly lynched and then were sentenced to death. The Communist Party took on the case when the NAACP wouldn’t touch it. It became an international cause, one of the girls recanted her claims, and finally they were exonerated, though the last did not leave prison until 1950. This is one of the most important events in American history. There is a tiny museum to it in Scottsboro, but it’s only open a couple of days a month and is in what looks to be a fairly run down old church. There’s a mural on a building painted by the first Black Disney cartoonist. But that’s it. Meanwhile, Scottsboro advertises the hell out of its bizarre museum/thrift store that is where unclaimed airline baggage ends up. OK then.

Down a country road, past a collection of ramshackle mobile homes, sits a 102-acre “shrine to the honor of Alabama’s citizens of the Confederacy.”

The state’s Confederate Memorial Park is a sprawling complex, home to a small museum and two well-manicured cemeteries with neat rows of headstones — that look a lot like those in Arlington National Cemetery — for hundreds of Confederate veterans. The museum, which director Calvin Chappelle said has about 30,000 visitors a year, seeks to tell an “impartial” history of the Civil War.

The museum’s exhibits explain what the White Alabamians who took up the cause of the Confederacy felt was on the line — Alabama was 10th of the then 33 states in the value of livestock, seventh in peas and beans, and second in cotton production. The only hope to save its economic position, the exhibit quotes a former state governor as saying, was for it to secede from the union, and though not mentioned directly, maintain the bondage of hundreds of thousands of Black Americans.

On a recent morning, there was just one visitor on the property and he didn’t enter the museum.

…

Chappelle explained that the purpose of the museum was to tell the stories of Confederate soldiers; visitors who want a fuller picture of Alabama’s racial history — slavery, reconstruction, Jim Crow and the Civil Rights movement — would have to go elsewhere.

There are a number of museums that tell those stories spread across Alabama, but the Confederate Memorial Park is different. It is the only museum in the state that has a dedicated revenue stream codified in the state’s constitution. So while other museums struggle to keep their doors open, search for grants for funding and depend on volunteer staff, the Confederate Memorial Park is flush with cash. In 2020 alone, the park received $670,000 in taxpayer dollars. That’s about $22 per visitor and more than five times the $4 admission price for adults.

Those are the kind of resources the volunteers at the Safe House Black History Museum in Greensboro, Ala., could only dream of. The small museum tells the little-known history of the rural grass-roots movement that paved the way for world-changing events like the 1963 March on Washington, where the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. delivered his famous “I Have A Dream” speech.

The museum consists of two shotgun houses, one of which is where King sought refuge from the Ku Klux Klan in 1968, just two weeks before he was murdered in Memphis. The items on display include the rusted back of a pickup truck from which King once gave a speech after being unable to find a local church that would risk letting him speak in their building.

“We were invisible people,” Theresa Burroughs, the museum’s founder and a civil rights activist who received a Congressional Gold Medal for her participation in the 1965 march from Selma to Montgomery, Ala., says in a video that plays on a television in the museum.

The exhibits Burroughs crafted tell the stories of people in Alabama’s “Black Belt” who worked in the shadows to make the civil rights movement successful. But with limited funding, it’s hard for the museum to make the history of those “invisible people” known today. Confederate Memorial Park is open seven days a week. The Safe House museum can only open its doors by appointment.

Historical memory matters because it reflects the priorities of a society. It’s not just Alabama either. Lots of places underfund museums that tell stories that don’t reflect the desired priorities of powerful people. It’s not as if South Boston has a museum to the racists that fought school busing. I’ve seen state museum leadership around the country turn hard to the right the moment their exhibit staff starts telling stories that might not fit the current priorities of the Republican Party. The Alabama case might be more pronounced, but it’s not exactly completely shocking.