Erik Visits an American Grave, Part 932

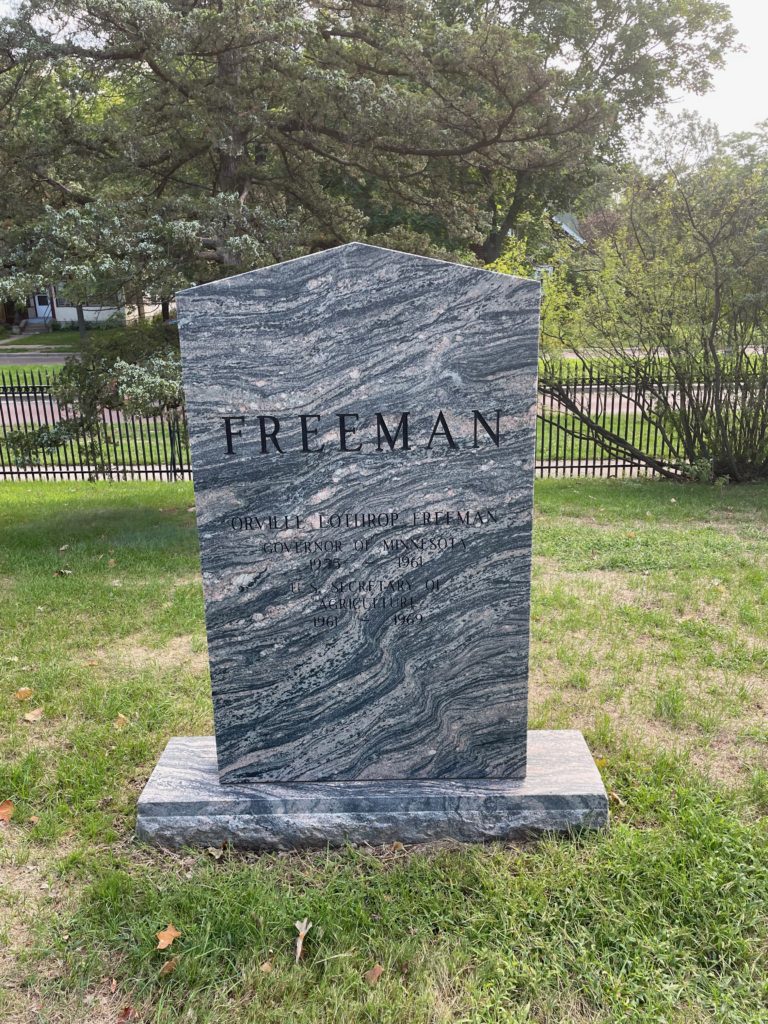

This is the grave of Orville Freeman.

Born in 1918 in Minneapolis, Freeman grew up a Depression child. His father owned a clothing store but he went bankrupt due to the Depression. But Freeman went to the University of Minnesota, and graduated in 1940 after supporting himself through college working as a janitor. He was classmates there with Hubert Humphrey, being on the university debate team together. They became lifelong friends and political allies in the Democratic Party (Democratic Farmer-Labor Party in Minnesota). He signed up with the Marine Reserves in 1940 and then went full-time when the nation entered World War II. He went through officer training and entered combat in 1943 at Bougainville, not the easiest place to start your battle career. He was shot in the jaw and arm just a few days later and that ended his military service as he lost a good bit of movement in the arm. He did get a Purple Heart for his wounds.

Freeman came back to Minnesota and went to law school at the University of Minnesota, finishing in 1946. While still in law school, Humphrey, now mayor of Minneapolis, named Freeman a special assistant on veterans affairs, beginning his governmental career. Freeman practiced law in Minneapolis after graduation. He was politically ambitious and was part of a group of young Minnesota Democrats that would help define postwar liberalism over the next four decades, including Humphrey and Walter Mondale. He got creamed in 1950 running for attorney general and then again in 1952 when he ran for governor. But he was not through. In today’s climate, two big losses would have made you a has-been. Wasn’t that way in the 50s. Freeman won his next bid to be governor in 1954 as a progressive liberal, a rejection of the conservative politics of the era and the Republican domination of Minnesota. He pioneering big television advertising for campaigns in this race, which definitely helped his bid. He was still a very young man without a long history of electoral office when he was elected governor, but he proved effective, winning reelection twice to the state’s two year terms. But in 1960, Freeman lost his re-eelction bid because when meatpackers went on strike, Freeman called martial law in order to keep the company from bringing in scabs, angering anti-union voters. He would never again run for elected office.

Freeman may have lost, but Democrats won the presidency. Freeman was a big enough player to get a major role in the new administration, as Secretary of Agriculture. Now, this is not often seen as a critically important position. It’s more one that goes to a Midwestern politician who largely remains pretty quiet during their tenure. But Freeman was a major exception to this, to the point that other than Henry Wallace (or perhaps both Henry Wallaces) may be the most important Secretary of Agriculture in the nation’s history. There were two sides to Freeman’s importance. First was fixing the endemic problem of overproduction and thus low prices for American farm goods. Two was employing America’s farm productivity for Cold War foreign policy purposes. Freeman excelled in making his department critical in moving forward on both issues. It also helped Freeman that he had spoken out strongly against the anti-Catholicism Kennedy faced in the 1960 election, especially important because Freeman was also a Lutheran deacon.

The overproduction issues were in some ways solved by the foreign policy. But in short, the Kennedy administration wanted to go farther than previous administrations in legally limiting the amount of a commodity that could be produced and brought to market. The goal was to cut production in order to raise prices and thus the incomes of those who remained farming while using the nation’s farm surpluses in order to feed hungry people, both in the U.S. and overseas. Freeman also wanted to reduce the budget while focusing more on research. So a serious reduction of grain going to livestock feed was undertaken. Research on growing food that would survive a nuclear attack was a big part of his program (ah, the Cold War).

When Lyndon Johnson began the War on Poverty, Freeman was a key part because of the food-centric nature of so many of those programs. It was Freeman and his top advisors who crafted the bill introduced into Congress in 1964 to create the food stamp program, one of the most enduring parts of the American welfare state, as limited as it may be today. In fact, Freeman somewhat limited the program at first because he demanded that most recipients pay something for the stamps so that it could supporter farmers more, which by 1968 liberals such as Robert Kennedy openly criticized. For whatever reason, Freeman simply could not believe that there were Americans so poor that they could not afford to buy food stamps. Basically, he didn’t spend much time out of Minnesota or Washington, D.C. and didn’t go to rural Mississippi or West Virginia. Freeman pushed hard for funding to build water and sewer lines in rural America. He also lobbied Congress to support greater consumer protections in food safety. Interestingly, whether LBJ told Freeman the truth is unknown, but Johnson told Freeman that JFK had told him that Freeman was the runner up for the VP job in 1960. He probably would have made a good president, especially in the liberal 60s.

Freeman also led the use of America’s agricultural production to help feed the world. That even included the Soviets. The Khrushchev era largely came to an end in the Soviet Union because of his abject failure in expanding Soviet food and consumer production. Freeman pushed for a massive grain sale to the Soviets to help them through it and of course show American superiority at the same time. He also led the Food for Peace program in his agency, distributing American agricultural surpluses to the global poor. He organized the massive export of American grain to India in 1962 to stop a famine there, significantly improving relations between the two nations.

Freeman stayed as Secretary of Agriculture through the Kennedy years and all the way through Lyndon Johnson’s full term, only leaving office when Richard Nixon took over the presidency in 1969. In the aftermath, he became president of the Business International Corporation in 1970. He led some consultancy businesses and basically lived the life of the senior lobbyist.

Freeman died of complications from Alzheimer’s in 2003, at the age of 84.

Orville Freeman is buried in Lakewood Cemetery, Minneapolis, Minnesota.

If you would like this series to visit other Secretaries of Agriculture, you can donate to cover the required expenses here. Ezra Taft Benson is in Whitney, Idaho and Charles Brannan is in Wheat Ridge, Colorado. Previous posts in this series are archived here.