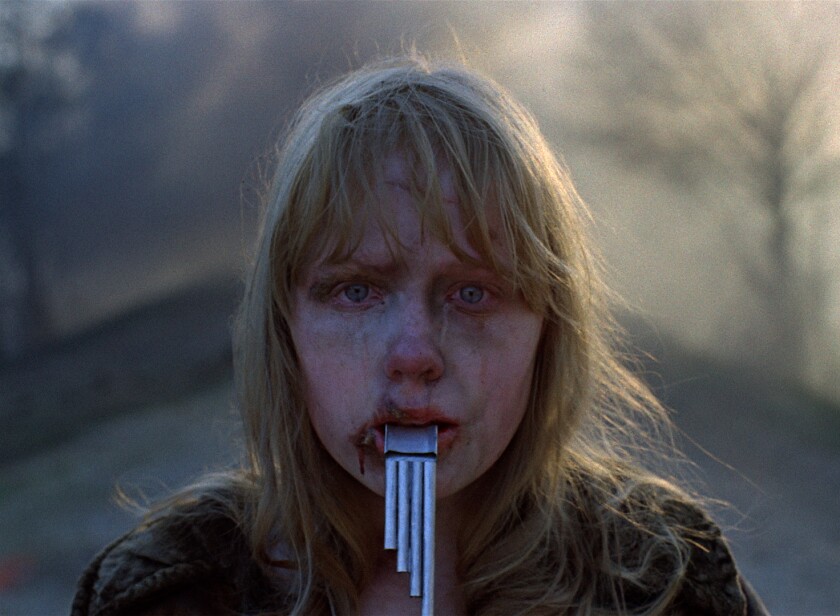

El dia de los muertos

Conor Friedersdorf has a pathetic bit of wishcasting in the Atlantic about how Never Trumpers should rally round a Ron DeSantis presidential run:

DeSantis frustrates and disappoints me within normal parameters. He hasn’t yet frightened me, as Trump does, as being superlatively incompetent, divisive, morally degenerate, or authoritarian. As MSNBC’s Joe Scarborough put it last June, when COVID-19 numbers were failing and DeSantis was peaking in the polls, “We’re going from the political heroin to the political methadone.” However bleak the analogy, that’s a significant step toward recovery!

All this is pointless, because Trump is going to be the 2024 GOP nominee, and anybody who doesn’t see that can be safely ignored.

Friedersdorf’s fellow Atlantic conservative David Frum is much more on point:

In 2016 and through the early part of Trump’s presidency, there was often an edge of Friars Club comedy to Trump’s rally performances: not very nice comedy, a little out of style in tone and sensibility, but comedy all the same. Not in 2021. Now it’s all dark and bitter.

Here’s video from a Georgia television station of the entirety of Trump’s Perry rally. Trump’s own speech starts at 1:37:38. Watch as much as you can stand and tell me if you detect even a moment of humor, Friars Club or otherwise. The most quoted bit—Trump’s quasi-endorsement of the Democrat Stacey Abrams as a better governor for Georgia than the Republican Brian Kemp—is not any kind of joke. It’s a deliberately delivered challenge, lower jaw jutting beyond the upper teeth, eyes slitted with anger.

That’s the guy who wants to return as the 47th president.

In Trump’s first term, the country was protected to some degree by his ignorance and ineptitude. He kept trying to do bad things, but it took him a while to figure out how the controls operated, where the kill-switches were located. By the time of his attempt to extort the Ukrainian president, in 2019, Trump had achieved a higher degree of mastery. But by then it was too late. Then the pandemic struck, and Trump bumped into a new wall of failure. In a second Trump presidency, however, the burglars will arrive already knowing how to bypass the alarms and disable the locks. He’ll understand that it’s not enough to install an ally as attorney general—he must control the secondary and tertiary ranks of the Justice Department too. He won’t allow himself to be talked into another chief of staff with an independent sense of duty, such as John Kelly, who averted much harm from the middle of 2017 to the beginning of 2019. It’ll be Mark Meadows types from day one to day last. And he’ll bring with them a new generation of Republican officeholders whose top priority will be rearranging their states’ election laws so that Republicans do not lose power even if they lose the vote.

That’s the future Trump is preparing.

Be ready.

Frum’s point about how Trump had no idea how the machine actually worked when he became president in 2017, but now he does, is particularly salient.

A basic difficulty we encounter when thinking about Trump and the GOP is that it’s impossible to disentangle adequately the extent to which Trump himself is the disease or the symptom. Obviously he’s both; but the extent to which a structuralist rather than an intentionalist understanding of Trumpism is appropriate is at the moment deeply unclear.

The problem is that Trumpism is both a cult of personality in the classic sense, and a particular individual’s exploitation, via a sort of shameless feral cunning, of everything about the contemporary American right wing that has made Trumpism possible.

So the question of the extent to which the Republican party has been Trumpified in the long run (in the Keynesian sense of the long run) is an open one.

But for the moment, it’s clear that, absent some sort of unforeseen external intervention, Trump is going to be the Republican candidate for president three years from now, and it’s quite unclear whether the American political system is going to survive that fact, no matter what happens in the election — or more properly the “election.”