This Day in Labor History: September 22, 1919

On September 22, 1919, steel workers went on strike in Pittsburgh and other steel cities. One of the most epic strikes of the post-World War I period, it was also a complete failure, one that demonstrated both the terrible political conditions for organizing after World War I and the deeply flawed American labor movement that needed drastic reform to succeed.

The struggle to organize steel had gone on for years by 1919. The Amalgamated Association of Iron and Steel Workers had won an early contract with Homestead Steel but that was crushed by Andrew Carnegie in 1892. The union nearly won another big strike in 1901, but failed in the end. By World War I, the AA was a shell of the militant organization it once was, yet also demanded exclusive representation in the steel mills.

Conditions for striking in 1919 were not propitious. The nation was in a full-fledged anti-union obsession by this time, with radicals being rounded up left and right, often for deportation. The AFL was most certainly not filled with radicals, but for companies, they wanted to put Samuel Gompers right back in his place. Gompers was so proud of the role the AFL played in World War I. Employers were….not. There’s a story about Gompers going to a dinner after the Armistice and talking in a toast about labor’s role in the postwar economy. Some capitalist replied that labor had no role at all and basically accusing Gompers of being a communist. The capitalist received letters from around the nation about his righteous patriotism against the evils of organized labor.

So the overall national conditions were bad for a strike. Moreover, the polyglot workers of the steel mills had not learned to love each other more after four years of war between their families in Europe. Ethnic tensions remained a major barrier to uniting around class. On top of this was the craft unionism that remained in the way of organizing effectively. The AA still existed, but unlike in the early 1890s, it represented a relatively few workers and had almost no organizing culture left. This was what the AFL used to pretend like it cared about industrial unionism in the mills. There were a total of 24 unions in all with a claim, as lots of craft workers were in their tiny labor associations, each one with its own interests and all with a seat at the table. The anachronistic form of American labor unionism was really not set up for success. The unions fought amongst themselves all the time. As the AFL moved toward a strike in steel, it sent the superb organizer and radical William Z. Foster to lead it, but he found himself facing great frustration with the unwillingness of the different unions to work together.

Conditions in the steel mills remained horrific. The standard work day was 12 hours. Safety considerations remained nearly nonexistent. Workers died all the time. The company couldn’t care less. The minimal requirements of workers compensation programs actually worked in the favor of companies, as they could easily pay that well below wage rates and would rather do so than face a worker’s lawsuit for injuries.

To say the least, U.S. Steel’s position on unions in 1919 had not advanced since Andrew Carnegie and Henry Clay Frick sent in the Pinkertons to bust the Homestead Works in 1892 before that conglomeration had even formed. When they discovered the AFL organizing again, they would be sure to have meeting halls shut for “safety violations,” ironic given the 24 hour workdays every other week in the steel mills where exhausted workers would make mistakes and then die in vats of molten steel. U.S. Steel brought the Pinkertons back for security.

Very slowly, glacially even, the unions moved toward a strike. Early in 1919, mine workers struck when the mines (which were closely connected to the mills as that’s where a lot of the coal went) when the companies had pressured the local politicians they owned to not allow spaces for meeting. The mayors quickly caved. The AFL kept putting off the strike. It really didn’t want to. It attempted to negotiate with U.S. Steel head Elbert Gary. He had no interest. It attempted to get Woodrow Wilson to intervene, but the president was focused on the League of Nations and wanted the coal companies on board with that.

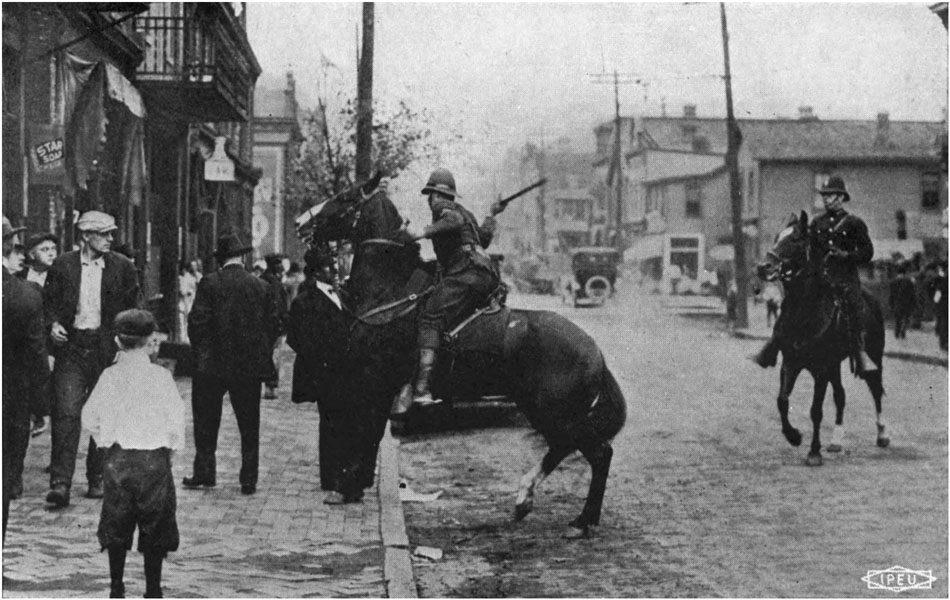

Finally, the AFL agreed to walk off the job on September 22. 350,000 workers across six states struck. This was a huge blow to the economy. U.S. Steel was not in the mood to compromise. It hated unions and it hated the World War I National Labor Board that gave workers a voice on the job for a short time. It wanted to end both. It had such a dominant media presence that it was easy to place stories about how a bunch of foreign leftists wanted to overthrow America, just like those Bolsheviks in the Soviet Union. Never mind that it was a big lie, who cared about that. Not many people. The police cracked down, arresting and fining people for such disturbances as laughing at the cops. Scabs poured in, mostly Black migrants from the South who were told there was good jobs but not told they were going to be used as strikebreakers. For U.S. Steel, this was all gravy, ensuring even more racial tension in the mills after the strike they could use to keep dividing workers. In fact, workers were eager to divide themselves on these lines. The arrival of strikebreakers, both Black and Mexican, in Gary, Indiana led to a full-fledged race riot that the National Guard put down, helping to suppress the strike as well.

Meanwhile, workers were really struggling. The wages were next to nothing. Workers were mostly willing to put up with the danger if they could get paid. But U.S. Steel wasn’t paying either. Said George Miller, one of the strikers, “There is not enough money for the workmen. We did not have enough money so that we could have a standard American living.” This was the kind of person whom U.S. Steel and the newspapers called a Bolshevik. The AFL was a disaster in organizing this thing. The AA demanded strike funds. Gompers replied that the AA also didn’t contribute strike funds to its own workers or anyone else. This was a divided action that really exposed the fault lines of American unionism.

By early January, the AA had given up and the rest of the AFL gave up shortly after. Chicago workers went back on the job by the end of October and Gary by November. The strike was over on January 8, 1920, a complete defeat for labor. It would take nearly two decades more to organize the steel industry. Meanwhile, this ushered in the worst decade in American labor history to that point, one that would nearly see the extermination of most unions by 1929.

This is the 408th post in this series. Previous posts are archived here.