The Thiel tendency in American politics

This story about what can formally be described as Peter Thiel’s youth is chillingly redolent:

Sometime around the spring of 1988, several members of the Stanford University chess team traveled to a tournament in Monterey, California, in an old Volkswagen Rabbit. To get across the Santa Cruz Mountains, they took California’s Route 17, a four-lane highway that is regarded as one of the state’s most dangerous because of its tight curves, bad weather, and wild-animal crossings. The chess team had no particular reason to hurry, but the 20-year-old driver of the Rabbit weaved in and out of lanes, nearly rear-ending cars as he slipped past them. For large portions of the trip, he seemed to be flooring the accelerator.

Peter Thiel was at the wheel. Thin, dyspeptic, and humorless, he had seemed like an alien to his classmates since arriving at Stanford two and a half years earlier. He didn’t drink, didn’t date, didn’t crack jokes, and he seemed to possess both an insatiable ambition and a sense, deeply held, that the world was against him. He was brilliant and terrifying. He was, recalled one classmate, Megan Maxwell, “a strange, strange boy.”

Thiel looked up when, predictably, the lights of a police cruiser appeared in his rearview mirror. He pulled the Rabbit over, rolled down the window, and listened as a state trooper asked if he knew how fast he was going. The other young men in the car — relieved to have been stopped but also afraid of how this might play out — looked at each other nervously.

Thiel addressed the statie coolly in his usual uninflected baritone. “Well,” he said, “I’m not sure if the concept of a speed limit makes sense. It may be unconstitutional. And it’s definitely an infringement on liberty.”

Unbelievably, the trooper seemed to accept this. He told Thiel to slow down and have a nice day. Even more unbelievably: As soon as he drove out of sight, Thiel hit the gas pedal again, just as hard as before. To his astonished passengers, it was as if he believed that not only did the laws of California not apply to him — but that the laws of physics didn’t either. “I don’t remember any of the games we played,” said the teammate who was riding shotgun, a man who is now in his 50s. “But I will never forget that drive.

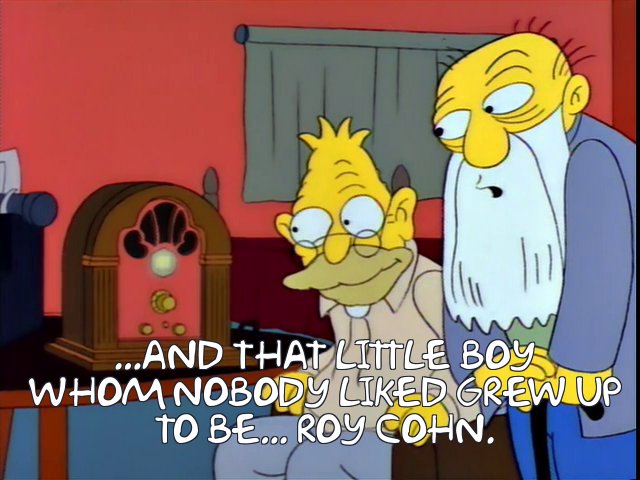

The idea that speed limits abrogate any legal or moral liberty interest no more absurd than claims that vaccine mandates do, and the vast majority of elite Republicans are now playing the role of the creepy young libertarian vampire or the willfully gullible state trooper in that scenario.