Erik Visits an American Grave, Part 892

This is the grave of William Belknap.

Born in 1829 in Newburgh, New York, Belknap grew up well off and went to Princeton. This was not a surprising choice. Princeton was the Ivy for Democrats and Belknap came from a big New York Democratic family. He then went on to Georgetown to study the law and he passed the bar in 1851. Like a lot of young men, Belknap decided that moving west provided more opportunities for an ambitious person than staying on the east coast. So he chose Iowa. Moving from DC to Iowa is not a choice a lot of people might make in 2021, but I guess it made sense at the time. The past truly was a different place. He opened a law practice in Keokuk.

Like many of the 19th century figures this series has profiled, Belknap saw the law as a springboard into politics. He became a leader in the state’s Democratic Party, even though he was still quite young. He served one term in the Iowa legislature in the late 1850s and was a captain in the local militia. Then the South committed treason in defense of slavery. Belknap was a Democrat. And as a Princeton man, he definitely knew southerners. But he was a Union Democrat and so there was no thought of him going to the South or even really sympathizing with the traitors. Instead, he joined the Union Army, was made a major, and equipped the 15th Iowa Volunteers. His men saw action too. They were central at Shiloh, backing up the depleted soldiers at the Hornet’s Nest when they arrived on April 6, 1862. These were pretty raw troops to be thrown into that hell. Belknap performed pretty well, receiving a slight wound and his horse was shot and killed from under him (which may be how he was wounded). He did well at Corinth too, taking over as acting commander when the colonel in command of the 15th Iowa was wounded at Shiloh. This led to his promotion to lieutenant colonel in August 1862. His men played a key role at Vicksburg as well. They were on Sherman’s march through Georgia, engaging in hand to hand combat when the 45th Alabama crossed into Union lines. He was promoted to brigadier general in July 1864. Overall, Belknap was a quite good officer.

The experience of war convinced Belknap to become a Republican. But as someone who was close to a lot of Democrats, it placed him in a prime position for patronage. Andrew Johnson named him Collector of Internal Revenue for Iowa. This was a first-rate patronage position because the collector got to keep a portion of the collected revenues for himself. Although such a position might be ripe for the corruption that was so common after the Civil War, Belknap’s books were quite clean. That’s interesting in light of what is to come.

After four years back in Iowa, President Grant named Belknap Secretary of War. Other than being a capable officer in the war, there was no good reason to name him to this position. But competence and capability were at best minor concerns in Gilded Age Cabinet selections. It was the politics and party factionalism that were more important. Grant’s initial Secretary of War was John Rawlins, but he died of tuberculosis later in 1869. The one thing Belknap had going for him was that Sherman liked him and of course Grant respected Sherman. So that was enough. Belknap would prove to be a quite controversial Secretary of War, for reasons that reflect the politics of the time in ways that are interesting to how we remember this period today.

Belknap did not repay Sherman for his patronage, reducing the authority of the General of the Army and reducing his budget. Sherman was so mad at his protege that he left Washington for St. Louis. Many Republicans also never trusted Belknap because he used to be a Democrat. The flip side of this was that southern Democrats and their supporters hated Belknap because the Grant administration had used the Army to crush the Ku Klux Klan. Belknap really wasn’t that powerful in the administration and Grant was going to do whatever he wanted here, but I guess they wanted him to resign in protest or something. Anyway, more on this later.

Unlike Sherman or Philip Sheridan, Grant wanted peace with the tribes on the Plains. The other guys? They were all-in for genocide and were tremendously frustrated with their old commander. As Secretary of War, at least some of this came under Belknap’s purview. And he took advantage of that. See, as the reservation system developed, it was fraught with political possibilities. In the patronage system, well, that was a lot of key positions to fill. And in an era where corruption was too tolerated to begin with, corruption aimed against people most Americans saw as barely human beings was even more acceptable. Belknap made it his top priority to create that patronage system. In 1870, he got Congress to give him the power to name Indian agents based at military forts in the West. This was another way that he angered Sherman, as naming those lucrative monopoly positions had belonged to the Army before this. Both soldiers and Native Americans bought from these monopolies. The prices were quite high. So you can see where this is going.

Now, Belknap’s first wife had died in 1862 and his second wife liked nice things. The salary of a Cabinet official wasn’t really that high. They liked to host big parties. They massively overspent here and sometimes their lavish gatherings got out of hand. Once, a huge drunken party cost a lot of damage to the big house they rented. They didn’t have the money to pay for the damages. But what they did have was the agents. So what happened was that his wife wanted him to name one of her friends to be the agent at Fort Sill. But the agent at Fort Sill didn’t want to leave the job. So everyone made a deal. The current agent would pay Belknap’s friend $12,000 a year. Half of that would then be kicked back to Carlita Belknap, to keep it out of William’s name at least. Now, Carlita died of tuberculosis soon after giving birth in 1870. So he brought her sister Amanda on board to handle the payments, which theoretically were for the child’s education but of course were not. The baby died in 1871. Payments still came in. Carlita’s sister went on a sweet trip to Europe. Belknap stayed on the job. He then married Amanda in 1873. She also liked the high living, even more than her sister, to the point where the media noticed. So the payments still continued. No one really knew how the Belknaps had all that money.

Belknap did other fun things too. He explicitly violated American neutrality in the Franco-Prussian War by selling arms behind the nation’s back to the Remingtons of gun fame and then later bullets for those guns that went to the French. This led to a congressional investigation, but nothing happened to Belknap. He also intervened to save the negatives of the broke Civil War photographer Matthew Brady, which was a tremendous service to the nation given the importance of that work in how we understand the Civil War today. Basically, he got Congress to pony up $25,000 for them and to pay off Brady’s creditors. He was involved in the decision to not enforce treaties with the Lakotas and allow white miners to enter the Black Hills, though like many things concerning the military in these years, Grant was going to do that anyway.

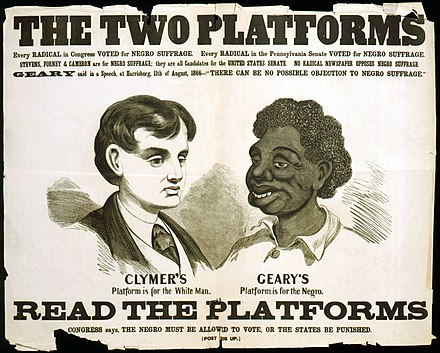

So, in 1876, the corruption came to light. That Belknap was grotesquely corrupt is unquestionable. But how it came out also says a lot. Belknap’s former roommate at Princeton was a guy named Hiester Clymer. Fast forward thirty years or so and Clymer, who most certainly did not join the Republican Party like Belknap did and who was one of the most reprehensible white supremacists in American political history (which really says something!) hated his old roommate. In fact, let’s remind ourselves of this infamous Clymer campaign poster.

Clymer was one of those politicians outraged that the Army would dare be used to put down a white supremacist terrorist campaign after the Civil War. Democrats had retaken Congress in 1874 due to the Panic of 1873, disgust over the corruption of the Grant administration, and good old fashioned American racism that Democrats whipped up. Had Clymer not so despised his ex-roomie, this might not have come to light. But Clymer was thrilled to be able to bust him, not because he cared about corruption, but because of the racial politics. So Clymer and House Democrats ran an investigation and decided to impeach him. At this point, the house of cards fell. Belknap went to Grant, told him it was all true, and resigned. The impeachment went ahead anyway. Testifying in favor of impeaching him was none other than George Armstrong Custer, about to meet his fatal end. Custer accused both Grant and Belknap of corruption. Grant was furious. He wasn’t corrupt. He was just incredibly tolerant of corruption. These two had already hated each other.

The Senate wasn’t really sure that it even had jurisdiction after Belknap was impeached. After all, he had already resigned. Once they did that they did, they voted 35-25 in favor of conviction, which was sort of the 2/3 majority required. So he was acquitted, sort of. But Grant was really angry at his former subordinate. He ordered the Attorney General to take the case over before the Senate trial and basically put Belknap under house arrest. He was indicted immediately after his Senate acquittal in D.C. Belknap begged Grant to let him off. Grant was unsure. The Cabinet was highly divided. Grant, being a big softy in the end and, again, way too tolerant of corruption, decided to do so. So Belknap only suffered a lost reputation, not the prison time he deserved. Instead, he and his wife went to Europe.

After all of this, Belknap left Washington permanently, first going to Philadelphia and then back to Iowa, where he restarted his law practice. Despite his bad reputation, he still had powerful connections so frequently represented wealthy clients, especially railroads who most certainly didn’t about his corruption since railroad execs were the crookedest bag of snakes every created. Belknap died in 1890 of a heart attack. He was 61 years old.

Belknap’s Senate trial was used as precedent for the second impeachment of Donald Trump in 2021. Again, a criminal was not convicted.

William Belknap is buried on the confiscated plantation of the traitor Lee, Arlington National Cemetery, Arlington, Virginia.

If you would like this series to visit other corrupt Cabinet officials, you can donate to cover the required expenses here. Unfortunately, all the Trump Cabinet appointees still live (oh god will I enjoy the Steve Mnuchin post if the blog and I still exist by that point) so I have to be patient and outlive them. Albert Fall is in El Paso, Texas and Simon Cameron is in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania. Previous posts are archived here.