Where is everybody?

This is a very cool (true) story:

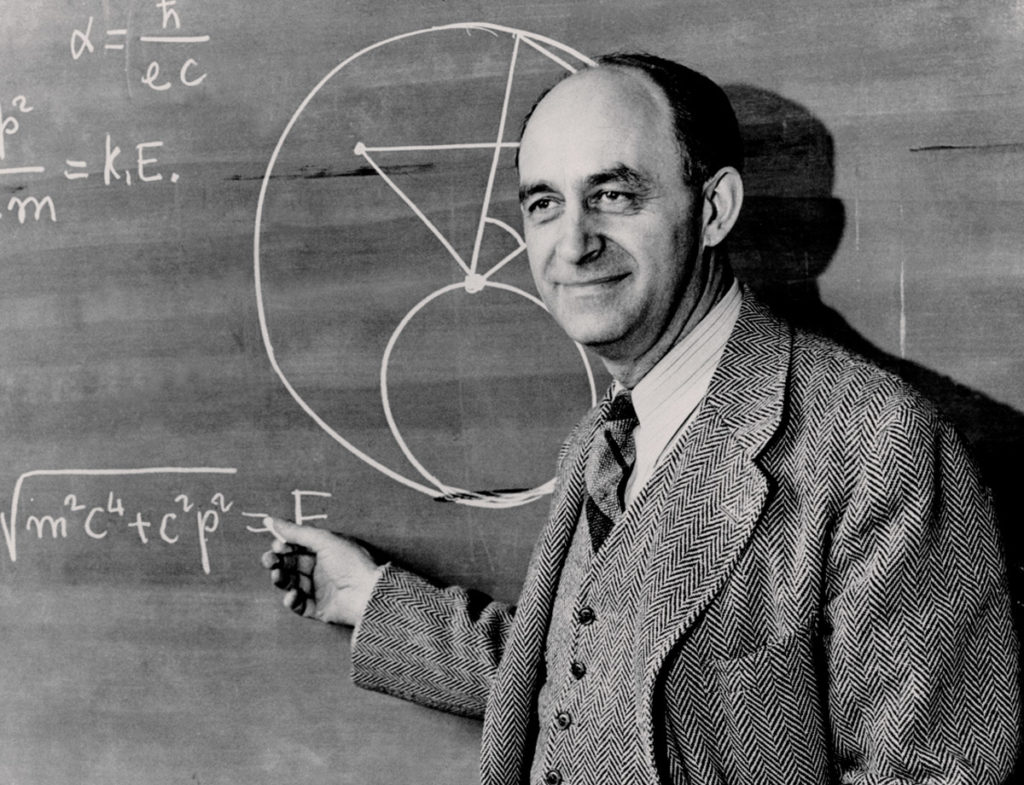

In the summer of 1950 at Los Alamos National Laboratory in New Mexico, Fermi and co-workers Emil Konopinski, Edward Teller, and Herbert York had one or several casual lunchtime conversation(s).

Herb York does not remember a previous conversation, although he says it makes sense given how all three later reacted to Fermi’s outburst. Teller remembers seven or eight of them at the table, so he may well be remembering a different previous conversation.

In one version, the three men discussed a spate of recent UFO reports while walking to lunch. Konopinski remembered mentioning a magazine cartoon which showed aliens stealing New York City trash cans, and as he wrote years later, “More amusing was Fermi’s comment, that it was a very reasonable theory since it accounted for two separate phenomena.”

Teller remembered Fermi asking him, “Edward, what do you think? How probable is it that within the next ten years we shall have clear evidence of a material object moving faster than light?”. Teller said, “10–6” (one in a million). Fermi said, “This is much too low. The probability is more like ten percent” (which Teller wrote in 1984 was “the well known figure for a Fermi miracle”).

At lunch, Fermi suddenly exclaimed, “Where are they?” (Teller’s remembrance), or “Don’t you ever wonder where everybody is?” (York’s remembrance), or “But where is everybody?” (Konopinski’s remembrance).

Teller wrote, “The result of his question was general laughter because of the strange fact that in spite of Fermi’s question coming from the clear blue, everybody around the table seemed to understand at once that he was talking about extraterrestrial life.” York wrote, “Somehow … we all knew he meant extra-terrestrials.

Fermi’s question can be interpreted as implicating a kind of paradox, captured well by Frank Drake’s very simple equation:

The equation is presented as follows:

Where the variables represent: N is the number of technologically advanced civilizations in the Milky Way galaxy; R_{*}}

is the rate of formation of stars in the galaxy; }

is the fraction of those stars with planetary systems;

is the number of planets, per solar system, with an environment suitable for organic life;

is the fraction of those suitable planets whereon organic life actually appears;

is the fraction of inhabitable planets whereon intelligent life actually appears; }

is the fraction of civilizations that reach the technological level whereby detectable signals may be dispatched; and }

is the length of time that those civilizations dispatch their signals. The fundamental problem is that the last four terms (L}

) are completely unknown, rendering statistical estimates impossible.

Since there are apparently more than a 1000 billion galaxies in the observable universe, and on average these galaxies contain tens or hundreds of billions of stars each, that’s like . . . a lot of stars. It’s so many stars that even if you assume that life arises in a tiny fraction of star systems, and that technologically advanced life arises on a tiny fraction of that tiny fraction, a tiny fraction of a tiny fraction of a trillion times a hundred billion is still . . . a lot of ETs.

This in turn leads to some existential questions, such as, if there have been a lot of technologically advanced civilizations out there, does the fact that we have to this point collected precisely zero evidence of this indicate that these civilizations/species inevitably wipe themselves out before successfully undertaking interstellar colonization on a galactic scale, and/or providing any observable evidence of their existence on even an intergalactic scale?

The recent spate of renewed interest in UFOs/UAPs led the Pentagon to issue a report that concluded that we don’t know anything about anything, which seems pretty accurate to me:

The nine-page report released by the Director of National Intelligence’s (DNI) office last week, formally titled “Preliminary Assessment: Unidentified Aerial Phenomena,” says a little bit more than “we know nothing.” But that is the main takeaway. “Limited Data Leaves Most UAP Unexplained” reads the report’s first subject heading.

That takeaway comes as something of an anticlimax capping off a period of frenzied speculation over UAPs (the new preferred term for “UFO”). The current mania was kicked off by a 2017 New York Times A1 article revealing the existence of a quiet Pentagon program analyzing strange aerial sightings by pilots. Since then, a steady stream of mainstream news coverage and Pentagon disclosures have kept UAPs in the public eye, complete with details about their allegedly fantastical, above-human capabilities.

In the immediate wake of the DNI report, no minds have been changed. The skeptics are still skeptical. Believers in the “extraterrestrial hypothesis” (ETH) still believe.

Dylan Matthews’s write-up about all this does a good job of summarizing the existential anxieties generated by The Great Filter Theory (basically any species that gets advanced enough to produce Enrico Fermi will also produce Ben Shapiro and thus inevitably destroy itself), and by the perhaps even more awe-inspiring idea that intelligent life is such a freakish development that the real reason we haven’t seen any evidence of anybody else being out there is that there never has been:

In 2017, Anders Sandberg, Eric Drexler, and Toby Ord of the Future of Humanity Institute attempted rough estimates of the odds that human civilization is alone in the galaxy and universe by giving uniform odds to a number of different parameters. For instance, they estimated that the share of planets with life that also have intelligent life could be anywhere from 0.1 percent to 100 percent, and gave equal odds to every number in that range.

They then incorporated the fact that we haven’t observed other intelligent civilizations, which should lower our estimated odds of their existence. The paper concluded that there’s a 53 percent to 99.6 percent chance of humans being the only intelligent civilization in the Milky Way, and a 39 percent to 85 percent chance of being alone in the observable universe.

Matthews’s underlying framing of all of these questions is captured by his conclusion:

Getting to the bottom of the UAPs and investigating whether there’s intelligent life elsewhere is important, and it’s probably worth devoting government resources toward solving the mystery.

But I also worry that belief in the extraterrestrial hypothesis is a kind of wishful thinking. If it’s wrong, and a Great Filter is in our future, that suggests our species is in immense danger. It would mean there are many, perhaps millions or billions, of civilizations like ours around the universe, but that they without fail destroy themselves at some point after they reach a certain level of technological sophistication. If that happened to them, it’ll almost certainly happen to us too.

If the extraterrestrial hypothesis is wrong simply because we’re the only species that has even gotten this far, that’s alarming for a different reason. It implies that if we screw up, that’s it: The universe would be left as a desolate compilation of stars and planets without any thinking creatures on them. Nothing capable of empathizing or acting morally would exist anymore.

I have to say that this way of framing the matter makes no sense to me and never has. Matthews, like so many people who address this issue, just axiomatically assumes a non-teleological universe. But then he poses a bunch of existential concerns that are only coherent from some sort of teleological perspective. I mean the companion question to Where is Everybody has always been And Does Anybody Besides Us Care and Why Should They?