Erik Visits an American Grave, Part 871

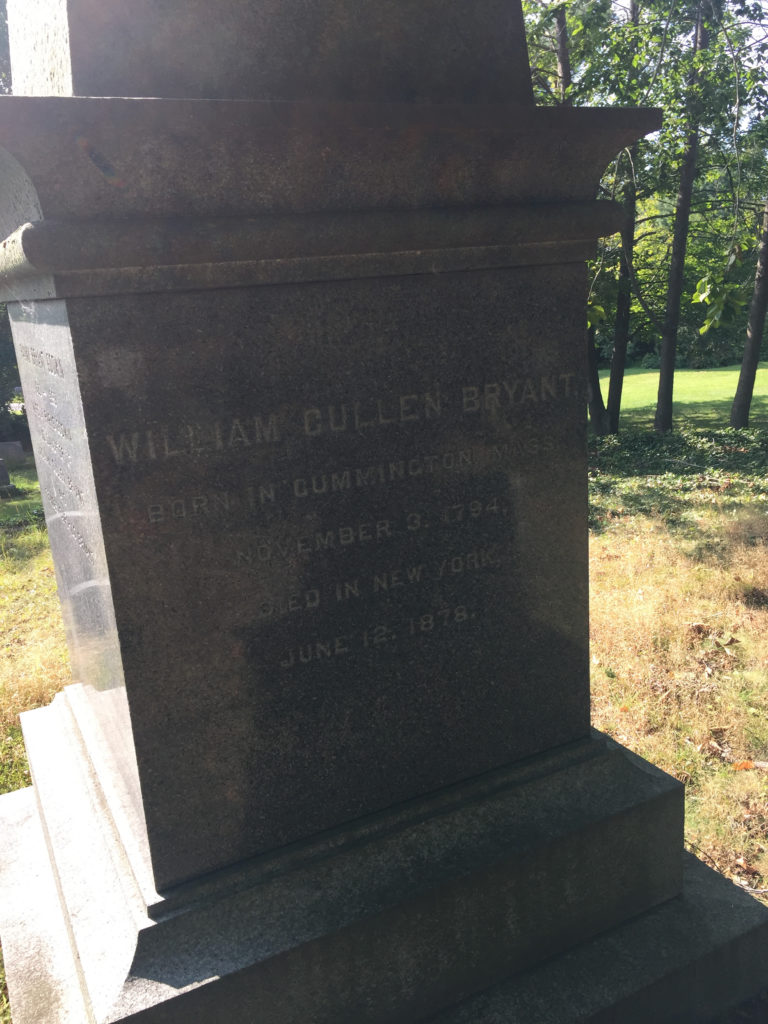

This is the grave of William Cullen Bryant.

Born in 1794 in Cummington, Massachusetts, Bryant grew up fairly well off for late eighteenth century New England. His father was a doctor who served in the state legislature. On the other hand, this still meant he was born in a log cabin. His family was old Puritan, going all the way back to the Mayflower, something that still really matters to New England (trust me, talk to any old white wasp Rhode Islander with any interest in history and they will claim a family connection to Roger Williams). Bryant was a real smart kid but the family didn’t have that much money. He went to Williams College for a year so he could transfer to Yale. But the family didn’t have the money for Yale. Instead, Bryant’s father suggested the law. This didn’t really interest Bryant. But still, you have to pay the bills. So he began to study for the bar. He was admitted to the bar in 1815 and began practicing in Plainfield, Massachusetts.

Now, Bryant had loved poetry since childhood. His family encouraged this as well. So while he practiced law, he also spent a lot of time writing poetry. In fact, in 1808, he published his first poem–a verse attack on Jefferson’s Embargo! It sold well too, because it parroted the views of New England Federalists plus who was this 14 year old? I can’t imagine this is a good poem. In 1811, Bryant started working on “Thanatopsis,” which would become his most famous work. It took years. And he lingered around it. Finally, in 1817, his father submitted it for him, along with some of his own work. The critics seem to have been fairly indifferent about the father’s work, but they found “Thanatopsis” fascinating. Might as well reprint it here:

To him who in the love of Nature holds

Communion with her visible forms, she speaks

A various language; for his gayer hours

She has a voice of gladness, and a smile

And eloquence of beauty, and she glides

Into his darker musings, with a mild

And healing sympathy, that steals away

Their sharpness, ere he is aware. When thoughts

Of the last bitter hour come like a blight

Over thy spirit, and sad images

Of the stern agony, and shroud, and pall,

And breathless darkness, and the narrow house,

Make thee to shudder, and grow sick at heart;—

Go forth, under the open sky, and list

To Nature’s teachings, while from all around

Earth and her waters, and the depths of air—

Comes a still voice—Yet a few days, and thee

The all-beholding sun shall see no more

In all his course; nor yet in the cold ground,

Where thy pale form was laid, with many tears,

Nor in the embrace of ocean, shall exist

Thy image. Earth, that nourished thee, shall claim

Thy growth, to be resolved to earth again,

And, lost each human trace, surrendering up

Thine individual being, shalt thou go

To mix for ever with the elements,

To be a brother to the insensible rock

And to the sluggish clod, which the rude swain

Turns with his share, and treads upon. The oak

Shall send his roots abroad, and pierce thy mould.

Yet not to thine eternal resting-place

Shalt thou retire alone, nor couldst thou wish

Couch more magnificent. Thou shalt lie down

With patriarchs of the infant world—with kings,

The powerful of the earth—the wise, the good,

Fair forms, and hoary seers of ages past,

All in one mighty sepulchre. The hills

Rock-ribbed and ancient as the sun,—the vales

Stretching in pensive quietness between;

The venerable woods—rivers that move

In majesty, and the complaining brooks

That make the meadows green; and, poured round all,

Old Ocean’s gray and melancholy waste,—

Are but the solemn decorations all

Of the great tomb of man. The golden sun,

The planets, all the infinite host of heaven,

Are shining on the sad abodes of death,

Through the still lapse of ages. All that tread

The globe are but a handful to the tribes

That slumber in its bosom.—Take the wings

Of morning, pierce the Barcan wilderness,

Or lose thyself in the continuous woods

Where rolls the Oregon, and hears no sound,

Save his own dashings—yet the dead are there:

And millions in those solitudes, since first

The flight of years began, have laid them down

In their last sleep—the dead reign there alone.

So shalt thou rest, and what if thou withdraw

In silence from the living, and no friend

Take note of thy departure? All that breathe

Will share thy destiny. The gay will laugh

When thou art gone, the solemn brood of care

Plod on, and each one as before will chase

His favorite phantom; yet all these shall leave

Their mirth and their employments, and shall come

And make their bed with thee. As the long train

Of ages glide away, the sons of men,

The youth in life’s green spring, and he who goes

In the full strength of years, matron and maid,

The speechless babe, and the gray-headed man—

Shall one by one be gathered to thy side,

By those, who in their turn shall follow them.

So live, that when thy summons comes to join

The innumerable caravan, which moves

To that mysterious realm, where each shall take

His chamber in the silent halls of death,

Thou go not, like the quarry-slave at night,

Scourged to his dungeon, but, sustained and soothed

By an unfaltering trust, approach thy grave,

Like one who wraps the drapery of his couch

This is not really my thing, but hey, whatever. It’s important in American literature. Initially, Richard Henry Dana (senior, not the Two Years Before the Mast son), who edited the North American Review, believed Bryant might have stolen it. He said he had seen nothing of this quality on this side of the Atlantic. But nope, Bryant was good at this. It was a huge sensation. It also made Bryant $15.

The lack of money in poetry led Bryant to keep plugging away at the law until the 1820s. In 1821, he got an invite from the Phi Beta Kappa chapter at Harvard to give a talk. So he wrote a long verse poem about American history up to the Revolution to present there. “The Ages” would be the first poem in Bryant’s soon to be published book Poems, that also included “Thanatopsis.” This is widely considered to be the first major book of poetry in American history. But still, it would take until the 1830s before he received wide recognition and some sense of financial stability. He finally decided to leave western Massachusetts for New York in 1825 and commit himself to the literary life. He had enough friends in the literary world of the U.S. to make this work by then, even if he wasn’t able to support himself through poetry. He became editor of the New York Review and then, when that wasn’t make much money, worked on the New York Evening Post as well. The Evening Post had been Alexander Hamilton’s paper. Bryant soon took it over. He also moved it significantly to the left. Even if he had started his literary life attacking Thomas Jefferson, by the 1820s, a supporter of Andrew Jackson and then even later, a supporter of anti-slavery third parties. He was for democracy and freedom, broadly defined. He came out in support of organized labor and used his platform to support strikes at a time when this was quite rare. He defended Irish immigrants against a readership that was strongly anti-Irish. He supported prison reform and abolitionism. He was an early member of the Republican Party, supported John C. Frémont in 1856 and then was a big supporter of Lincoln in 1860, when a lot of Republicans questioned whether the Illinois yokel should be their standard bearer instead of a more bombastic Republican like Seward or Chase. In fact, it was Bryant who introduced Lincoln at his legendary Cooper Union speech.

Bryant continuing writing, publishing, and editing through his long life. By the time of the Civil War, he was truly one of America’s established intellectual elites. He mentored young poets such as Walt Whitman was a strong advocate for an American literary nationalism that broke from British traditions. He was key in the foundation of the Metropolitan Museum of Art and helped found the New York Medical College. He remained influential in American culture at least to the point when Martin Luther King would frequently quote him in speeches.

Bryant spent the rest of his life in New York after his 1825 move. He died in 1878, at the age of 83.

William Cullen Bryant is buried in Roslyn Cemetery, Roslyn, New York.

If you would like this series to visit other 19th century American poets, you can donate to cover the required expenses here. If you look in the Library of America’s 19th century poetry box set, Carlos Wilcox, just before Bryant, is in Hartford, and Maria Gowen Brooks, just after his entries, is in Brooklyn, which must have been an interesting journey given that she died of a tropical fever in Havana. Previous posts in this series are archived here.