Erik Visits an American Grave, Part 864

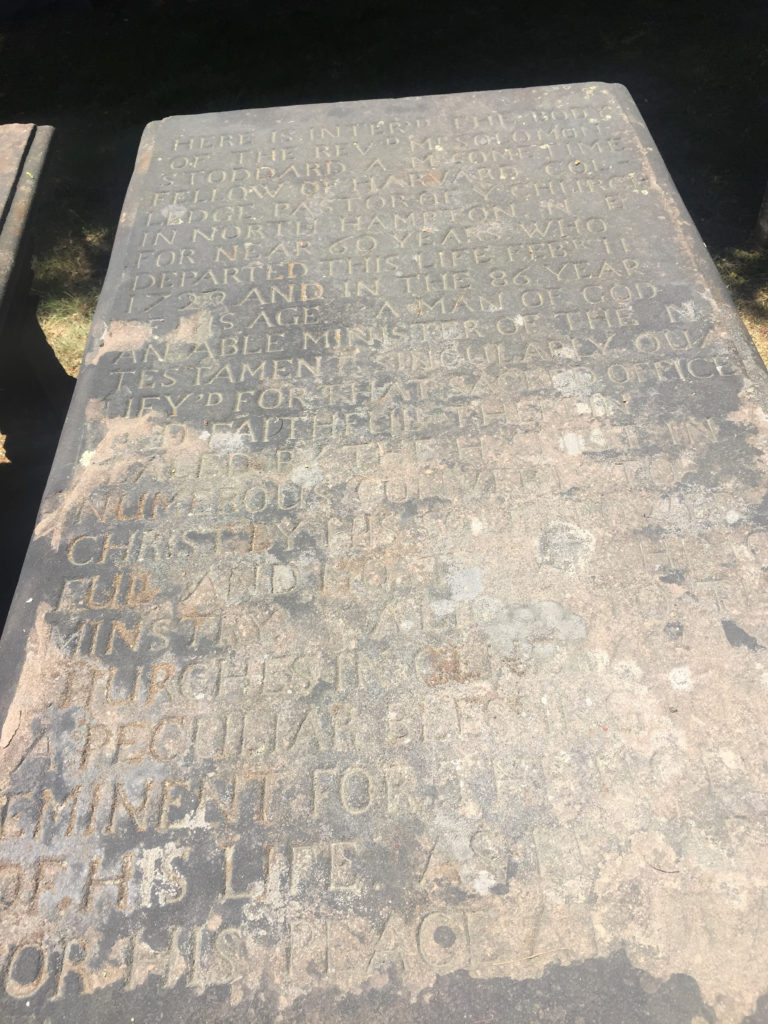

This is the grave of Solomon Stoddard.

Born in 1643 in Boston, Stoddard became one of the first American born major ministers of the colonial era.

Stoddard grew up in what passed for the elite of early New England, which most certainly not elite by any English standards. But in a Puritan society suspicious of personal wealth, his family was comfortable, or at least as comfortable as anyone really could be in seventeenth century New England winters. Anyway, his father was a pretty well-off merchant. However, his mother died when he was 3. He went to the area’s most elite boarding school and was only permitted to speak Latin as a child, which seems utterly bizarre to me but it was the 17th century and what isn’t bizarre about it. He graduated from Harvard in 1662 and then got a master’s degree in 1665. He became British America’s first known librarian in 1667, when Harvard hired him to organize the books.

By this time, Stoddard was a young rising minister at Harvard, Puritan Massachusetts was having the same problem revolutionary fanatics always have: how do you pass the fanaticism down to the next generation? The answer is basically that you can’t. The children of revolutionaries don’t have the same experiences you do. That’s true of communist revolutions and it’s true of Puritan revolutions. The old men who ran the church just stopped admitting young people to the full church membership since they didn’t think any of their conversion experiences were real enough. The problem with that is full political participation required the conversion experience. What this increasingly meant as well is that the politics of this near-theocracy were run by dying men. Stoddard was one of the ministers who suggested the solution—what became known as the Halfway Covenant. The elites were initially furious about this, but it made sense. People would get most, but not all, rights to participate in the church and government, even without the classic Puritan conversion experience. This was hugely important, revitalizing the church and in many ways saving it from extinction. For hard-core Puritans, this was an evil on the road to—gasp—the Unitarianism that would dominate the liberal New England elite a century later, but there was no real way to continue the colonial experience without something like this.

Stoddard didn’t stay Harvard’s librarian for very long. Sick (hardly surprising given 17th century New England winters), he lived in Barbados from 1667-69 to improve his health and be the chaplain to the colonial governor there. He almost went to England from there to run a church, but instead accepted a pastorate back in Northampton, Massachusetts, which at that time was right on the frontier and subject to attack from the tribes trying to save their lives and cultures from the English vultures. He took that position when Eleazar Mather, brother of Increase and uncle of Cotton (The names! The names!) died. Stoddard soon married his widow and she dropped a mere 13 children in the marriage. Incidentally, the entire Mather family despised Stoddard’s Halfway Covenant, but I don’t know how they felt about the marriage.

Stoddard remained something of an iconoclast for the rest of his life, arguing against strict interpretations of Puritanism and a playing a key role in the liberalization of the Puritan experiment. Although Cotton Mather would become more famous in later centuries, when the two vigorously argued about the theology at the time, it was Stoddard who consistently won out because he was realistic instead of a fanatic.

The Puritans sometimes get a reputation for not being that brutal to Native peoples. This is a ridiculous claim. They were horrible genocidal bastards. The Pequot War of 1637 is enough evidence of this, but it continued and continued. Stoddard routinely compared Indians to wild animals, which needed to be hunted down with dogs. In fact, he influenced the colonial government to pass a law mandating the raising of Indian-hunting dogs that would be used to eliminate threats to the colonial expansion on the western border, in what is today central Massachusetts. In fact, Stoddard was nearly killed during King Philip’s War in 1676, which helped create his early fanaticism.

Although horrifyingly awful toward the tribes early in his life, by the time he was old, he was defending the rights of Native Americans. This kind of transformation was not all that uncommon, especially in New England. As the tribes became less of a threat, the liberal Christianity developing there pushed converting rather than killing. Whether Stoddard saw his previous advocacy of genocide as inconsistent with his late-life beliefs, I do not know, but by the 1720s, he was defending the rights of the remnant tribal populations. One might also argue that was very old and sentimental by that time; it’s not as if the descendants of Stoddard and other Puritans of his generation were all that nostalgic about the tribes when they moved to New York or Vermont or New Hampshire. The genocidal talk would continue, the closer one was to independent Native peoples.

Among the people Stoddard influenced was his grandson, Jonathan Edwards, who was an assistant pastor at the old man’s church for awhile.

Stoddard died in 1729, at the age of 85, one of the most important Puritan ministers, despite being largely forgotten today. He wasn’t a brilliant man. But he was a pragmatic and charismatic man, two things that kept the New England experiment alive a century after its founding.

Solomon Stoddard is buried in Bridge Street Cemetery, Northampton, Massachusetts.

If you would like this series to visit other American religious figures, you can donate to cover the required expenses here. Benjamin Warfield is in Princeton, New Jersey and Dorothy Day is in Staten Island, New York. Previous posts in this series are archived here.