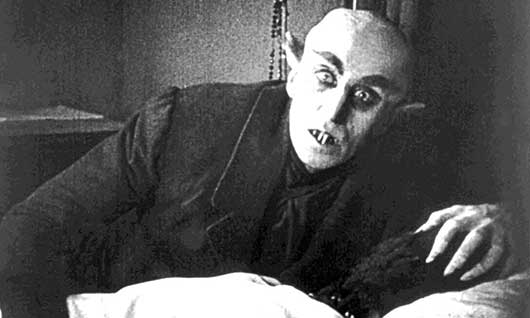

As of two years ago, metaphorical and aspiring literal vampire Peter Thiel had $5 billion in a Roth IRA

Roth IRAs were supposed to protect the “hardworking” (read: white people) “middle class” (read: white people) from the consequences of corporations getting rid of defined benefit pensions. The idea was you socked you nickels away in a Roth account, and you would never have to pay taxes on either what you invested or the capital gains on the investment, as long as you didn’t withdraw any of the money before you were 59 1/2. There were supposed to be strict limits on how much money you could shelter from taxes in this way, but of course this is America, so . . .

Yet, from the start, a small number of entrepreneurs, like Thiel, made an end run around the rules: Open a Roth with $2,000 or less. Get a sweetheart deal to buy a stake in a startup that has a good chance of one day exploding in value. Pay just fractions of a penny per share, a price low enough to buy huge numbers of shares. Watch as all the gains on that stock — no matter how giant — are shielded from taxes forever, as long as the IRA remains untouched until age 59 and a half. Then use the proceeds, still inside the Roth, to make other investments.

This is less than optimally framed by Pro Publica, the invaluable outfit that has gotten ahold of the tax returns of our plutocrats, since the whole point of this scheme is that people like Thiel could buy $2,000 stakes in dozens or hundreds of startups, since they needed just one of them to hit to acquire a gazillion percent non-taxable return on their initial investments. Hence:

While the scope and scale of such accounts has never been publicly documented, Congress has long been aware of their existence — and the ballooning tax breaks they were garnering for the ultrawealthy. The Government Accountability Office, the investigative arm of Congress, for years has warned that the wealthiest Americans were accumulating massive retirement accounts in ways federal lawmakers never intended.

At the same time, Congress has slashed the IRS’ budget so severely that the agency’s ability to ferret out abuses has been stymied. Money was so tight that at one point in 2015 the agency couldn’t afford to enter critical data about IRAs from paper tax filings into its computer system.

Over the years, a few politicians have tried, and failed, to crack down on the tax breaks the ultrarich receive from their giant IRAs.

In 2016, Sen. Ron Wyden, an Oregon Democrat, floated a detailed reform plan and said, “It’s time to face the fact that our tax code needs a dose of fairness when it comes to retirement savings, and that starts with cracking down on massive Roth IRA accounts built on assets from sweetheart, inside deals.”

“Tax incentives for retirement savings,” he added at the time, “are designed to help people build a nest egg, not a golden egg.”

But Wyden soon abandoned his proposal; there was no chance the Republican-controlled Senate would pass it.

Meanwhile, Thiel’s Roth grew.

And grew.

At the end of 2019, it hit the $5 billion mark, jumping more than $3 billion in just three years’ time — all of it tax-free.

Thiel, a fan of J.R.R. Tolkien, by then had brought his Roth under the auspices of a family trust company called Rivendell Trust. In “The Lord of the Rings,” Rivendell is a secret valley populated by elves, a misty sanctuary against forces of darkness. Thiel’s earthly version resides in a suburban Las Vegas office complex, across from a Cheesecake Factory, and is staffed by a small group of corporate lawyers.

And thanks to the Roth, Thiel’s fortune is far more vast than even experts in tallying the wealth of the rich believed. In 2019, Forbes put Thiel’s total net worth at just $2.3 billion. That was less than half of what his Roth alone was worth.

Pro Publica’s report details how a bunch of other plutocrats are also crouching on Smaug-like Roth hoards that can’t be taxed, because they’ve figured out how to drive an army of Brinks trucks through this particular loophole in the tax code.

As I’ve mentioned before, one thing I really don’t understand is why people who have hundreds of millions or billions or tens of billions or hundreds of billions of dollars — that is, people who are living in what is essentially a completely scarcity-free economic situation — aren’t a lot less worried about the effective tax rates they pay and a lot more worried that they might end up hanging upside down from a lamppost, on some sunny day in a future that is still unwritten.

I mean, if I had a billion dollars, I would personally price the value of not getting lined up against a wall etc. as essentially infinite, and the value of acquiring another billion dollars because my effective tax rate was low as, comparatively speaking, zero. On the other hand, compulsive obsessions are never easy to understand from the outside looking in:

When the accumulation of wealth is no longer of high social importance, there will be great changes in the code of morals. We shall be able to rid ourselves of many of the pseudo-moral principles which have hag-ridden us for two hundred years, by which we have exalted some of the most distasteful of human qualities into the position of the highest virtues. We shall be able to afford to dare to assess the money-motive at its true value. The love of money as a possession -as distinguished from the love of money as a means to the enjoyments and realities of life -will be recognised for what it is, a somewhat disgusting morbidity, one of those semicriminal, semi-pathological propensities which one hands over with a shudder to the specialists in mental disease. All kinds of social customs and economic practices, affecting the distribution of wealth and of economic rewards and penalties, which we now maintain at all costs, however distasteful and unjust they may be in themselves, because they are tremendously useful in promoting the accumulation of capital, we shall then be free, at last, to discard.Keynes, Economic Possibilities for our Grandchildren (1930)