This Day in Labor History: May 10, 1913

On May 10, 1913, white gold miners in the Transvaal region of South Africa went on strike in one of the first major strikes in that nation’s history and also one where workers allowed their racial interests to trump their class interests.

In 1910, the Union of South Africa formed. This was the British law officially granting white domination over people of color and creating The Union of South Africa from the various colonies in the region. Part of the goal of the new state was to organize the economy to produce for the colonial power. That included the gold mines, a major source of income for the British. The South African Party that ruled the nation after 1910 was closely tied to the gold capitalists.

Socialism did have a foothold in South Africa, with a variety of socialist parties that had connections to those in Britain. But, these parties were as deeply committed to white supremacy as the rest of South African whites. So when largely African miners went on strike in 1911, the South African Labour Party they had formed were right there with the ruling class and employers to crush their strike and force them back to work. What the Labour Party and associated socialist movements wanted was a unification of white workers–both English and Afrikaner–against the employers. But this extremely limited vision of change led to an obvious employer strategy–hire Black workers. The Labour Party, small as it was, did try to push an 8-hour day bill. It failed. With increasing dissatisfaction and organizing among African workers, whites moved toward striking, which they did, beginning in May 1913.

The more proximate reason for the strike came out of the New Kleinfontein mine. There, workers were fighting not only against long days, but serious health problems and dangerous working conditions. When they presented a list of demands, the mine fired the leaders. When one Saturday a manager ordered five mechanics to work three extra hours and they refused, the spark lit the fuse. A strike began. Union leaders attempted to get other mines to come out. Syndicalists–who also mostly believed in a revolution only for whites–also supported the strike trying to create their general strike-generated revolution. The mine owners then started hiring Black workers as strikebreakers. The unions tried to get those workers to respect the strike. But why would they, when the strikers were as committed to white supremacy as any other white?

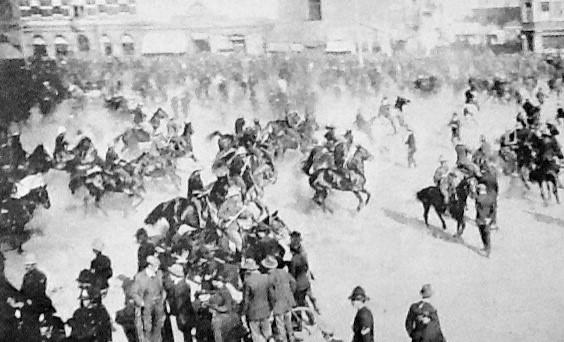

About 18,000 workers at 63 mines were on strike by the end of June. The state started to move to respond with force, a combination of police, British soldiers, and volunteer riflemen. The strikers themselves issued a call on June 29 that miners should come armed and ready to defend themselves. Things got even more heated on July 4 when police broke up a rally of 10,000 workers in Johannesburg’s Market Square with pickaxes and the government declared martial law. The same day, the Federation of Trades called for a general strike to support the miners. But again, this was only for whites and thus doomed to fail. The strikers did engage in some pretty hardcore militancy–burning a major newspaper office that consistently supported the mine owners. The next day, police opened fire on the miners, killing about 20 people.

That evening, South African leaders, fearful that the miners could burn Johannesburg, decided to meet with the strike leaders in Pretoria. The workers decided that if the government agreed it would look into their problems, they would go back to work. The government really did not want to do this. Said Jan Smuts, Deputy Prime Minister:

“We signed it because the police and Imperial forces informed us that the mob was beyond their control. If quiet was not restored anything could happen in Johannesburg that night. The town might be sacked, the mines permanently ruined.”

But it turned out to be a great idea for the companies. When the government agreed, this opened the door for the creation of company unions to siphon off any new attempt by radical workers to fight for better conditions by channeling that through meaningless shell unions that had no power. The syndicalists were outraged here–this was not going to bring about their revolution. And in the end, they were probably right, revolution or no. The strikers did get their jobs back, but that was about it in terms of any real victory by the miners.

Now, there had been some limited support for this strike by African miners, who of course faced utterly horrible conditions in the mines in which they worked. A few white workers began to argue that Africans should be able to join their unions, but as with white unionists in the United States, this sentiment was extremely limited and just as tenuous. When some African workers did strike, they were sent to prison for six months. The African National Congress, which had formed in 1912, decided to sit this one out. Hard to blame them.

The South African state followed up on the 1913 mineworkers’ strike with an even greater commitment to using military force to ensure that workers made no gains through striking. A rail strike the next year saw an even greater and more immediate use of force to crush it. The Labour Party continued to be hopelessly committed to white supremacy and simply would not do what was necessary to bring socialism to South Africa. Over time, the Communist Party split from the socialists and, like in the United States, would be the single most committed white organization to racial equality in the country.

This is the 391st post in this series. Previous posts are archived here.