The Continued Terribleness of Agricultural Labor

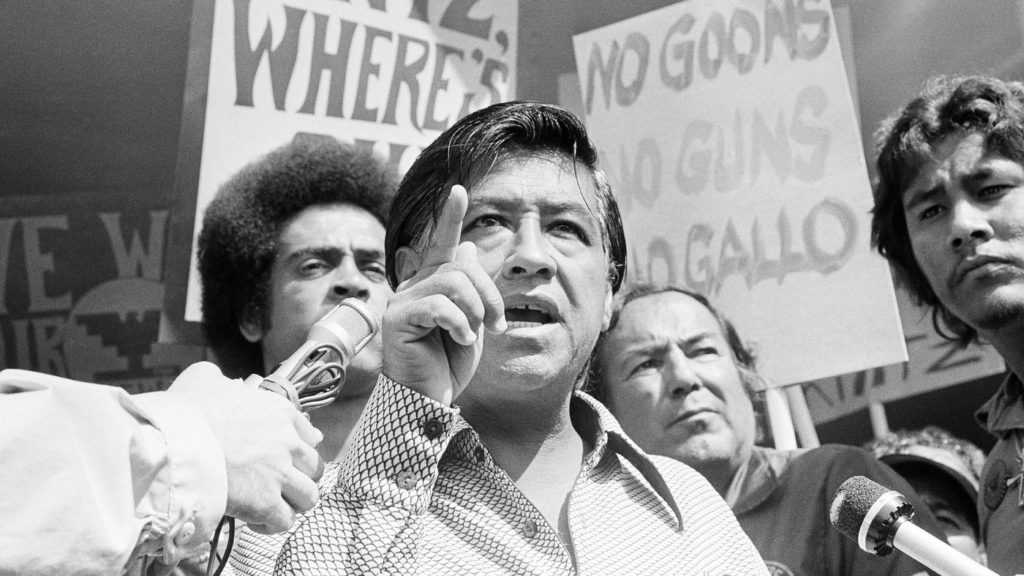

Cesar Chavez was a deeply flawed union leader, but he also had tremendous skills at creating an image of himself as a moral voice that took the plight of the nation’s forgotten farmworkers and made it a national outrage. The United Farm Workers soon became a cult of personality for him, often leaving the workers themselves behind as Chavez refused to listen to his own workers or anyone who challenged his authority. Not surprisingly, the UFW is today effectively irrelevant in the fields and is mostly a small organization the Chavez family runs as a memory industry. I know I am sounding harsh about all of this, but it’s true. That said, Chavez’s impact on the nation itself cannot be overestimated. Moreover, twenty five years or so after his death, he is still the individual most associated with the working and living condition of farmworkers. Unfortunately, things have not actually improved in the last quarter-century.

In a way, it hardly matters. The landmark California Agricultural Labor Relations Act, hailed as the most pro-labor law in the country, has barely been used for years. U.F.W. membership had already peaked when Mr. Chavez delivered the Commonwealth Club speech in 1984; today the union represents a tiny fraction of the farmworkers in California. Still, across the decades, some small, flickering hope endured. Maybe this year. Maybe some union will commit to the long, hard organizing necessary. Maybe thousands of farmworkers will line up in the fields to cast votes again, as they did in the 1970s, many for the first time in their lives.

The pandemic has something in common with Mr. Chavez’s movement: The crisis has made farmworkers visible. The impact of Covid-19 forced people to see the men and women who harvest their food — “essential workers,” yet essentially unprotected. Many are undocumented, their lack of legal protection now compounded by their vulnerability to the disease. Even if growers take precautions at work, social distancing is often impossible in overcrowded homes and overcrowded rides to work.

Over the past year, as I talked to friends in farmworker communities devastated by Covid-19, they spoke of friends who had fallen ill, relatives who died, families that grieved. I had spent the better part of a decade researching and writing about farmworkers and their history in California; now they were in the news, but there seemed nothing new to say. The pandemic was one more sad chapter of their story.

Eladio Bobadilla was 11 when he moved from Mexico to Delano, where his parents worked in the grape vineyards. Undocumented and frustrated by his lack of options, Mr. Bobadilla almost dropped out of high school; eventually, he became a historian of immigrants’ rights.

In some ways, he noted last week in a talk about Mr. Chavez, conditions in the fields are worse than they were decades ago. In real dollars, many farmworkers earn less now than they did in the 1970s. Before Mr. Bobadilla’s parents retired, they had to bring home the dirty trays they used to pick grapes during the week and wash them on their day off. They did not know, nor did their son, that was against the law; they knew only that they would lose their jobs if they did not comply.

“The struggle continues,” Mr. Bobadilla said. “It’s still a deeply exploitive type of work. It doesn’t have to be undignified work. It doesn’t have to be cruel work. It’s always been difficult. But it doesn’t have to be cruel.”

Indeed, it does not have to be cruel. But it took Chavez and an army of volunteers years of work to get consumers to care about any of this. And today, we care about the conditions in the fields about as much as consumers did in the years before the grape boycott–not one damn bit. Workers suffer and they die of heat exposure. They get poisoned by chemicals. They live in substandard housing. And it’s exceedingly rare to even have a cursory discussion of these issues, even in left and liberal circles. And when you do, it’s almost a throwback to Chavez, a memory that he existed, rather than a very serious problem today.