Preserving the Great Dismal Swamp

You might not at first glance think swamps have long human histories that require remembrance and memorialization, but in the context of slavery and escape, they are quite central to our history. Luckily, there are people fighting to remember and preserve:

Almost 20 years ago, Eric Sheppard picked up the slave narrative written by his distant ancestor, Moses Grandy, and set out to retrace his long trudge to freedom.

“Everywhere Moses Grandy went, I went,” Sheppard said. “The clues were left in Moses Grandy’s slave narrative for me.”

He started in Camden County, N.C., where Grandy was enslaved from the time he was born, and before long, the clues led him to the Great Dismal Swamp — the place where Grandy worked to buy his freedom.

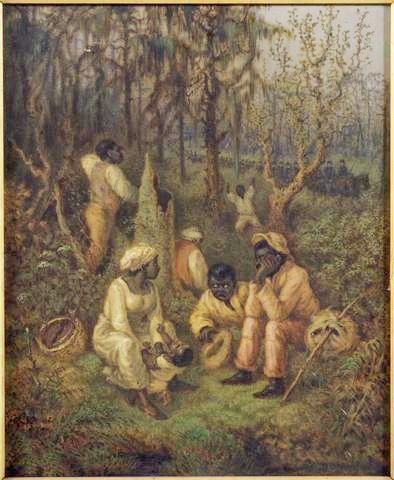

Straddling the North Carolina-Virginia border, the enormous, inhospitable morass was an ecosystem like no other in the region, and largely still is. Long an ancestral hunting ground for Native American tribes, the swamp became the site of grueling slave labor when George Washington and his Virginia business partners sought to develop the land in the 18th century. Grandy described the work conditions there in later decades as “very severe,” as the enslaved worked up to their chest in mud and water carving out ditches and canals.

But over time, the swamp took on an almost paradoxical identity. It became a passageway on the Underground Railroad — and, in its deepest reaches, the site of permanent maroon settlements where runaway African Americans and subjugated Native Americans found unlikely refuge. The swamp, said Marcus P. Nevius, author of “City of Refuge: Slavery and Petit Marronage in the Great Dismal Swamp, 1763-1856,″ was “both a place of slave labor’s exploitation and a place of Black resistance to that exploitation.”

And as he followed Moses Grandy into the Great Dismal, Sheppard could feel the weight of its complicated legacy settle on his shoulders.

“It was like an enlightenment, if you will. To take you into another realm of what happened there,” Sheppard said.

Now, Sheppard and a group of descendants of the swamp’s Indigenous and formerly enslaved refugees — called the Great Dismal Swamp Stakeholders Collaborative — are lobbying Congress to grant the swamp greater federal recognition in honor of their ancestors’ pursuit of freedom and security.

This is of course exactly the kind of thing Congress should fund, in this case declaring it a National Heritage Area, which opens up money for historical markers and the like. It’s a low-level investment in a critical part of American history.