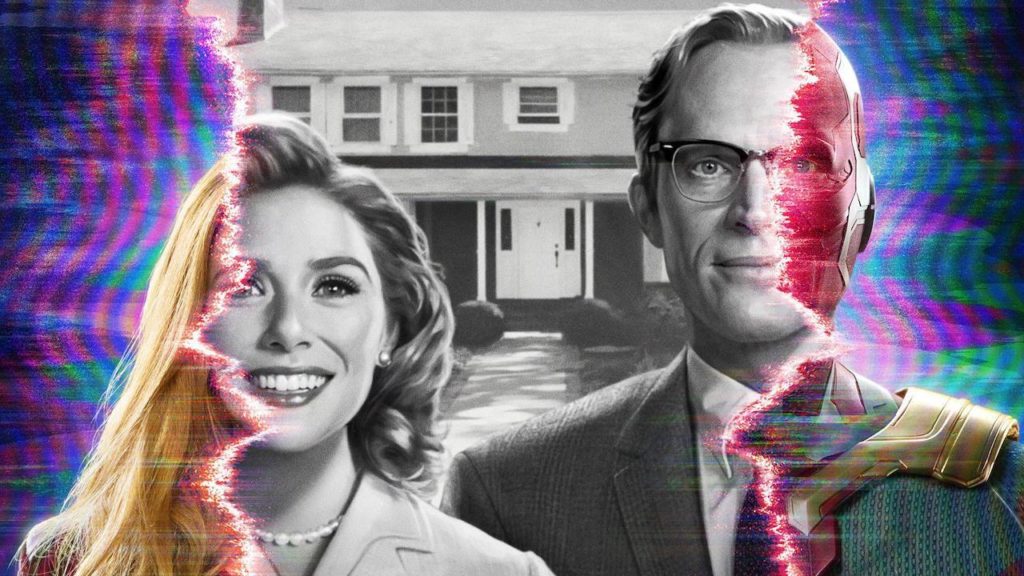

It’s WandaVision!

I’ll leave it to Steven to post about this week’s (extremely interesting) episode of The Falcon and the Winter Soldier, but in the comments to last week’s episode post, there was some demand for a WandaVision post. So here are a few links about the show that I found interesting (full disclosure: I thought WandaVision was and intriguing but ultimately failed experiment, one that exposes the fundamental flaws of the MCU, so most of these links come at it from that perspective).

My own (long) review gets into the way that WandaVision refuses to acknowledge its heroine’s culpability in her own actions, which ultimately forces it to twist its story and supporting characters past the point of incoherence.

Instead of delving into this rather intimate story and the character at its center, WandaVision seems determined to distract from it, not only with teasing, over-promising storytelling choices, but with the simple fact of its format. Much of the time, it feels as if the point of the show is the gag of its sitcom parody (though parody is probably too strong a word—imitation is closer to the mark). This a problem first because, as a sitcom riffing off some of the funniest shows in TV history, WandaVision is only mildly amusing, opting for tired jokes—Vision’s boss and his wife unexpectedly arrive for dinner! Wanda and Vision’s twins find a lost puppy and decide to take it in!—that not even its main characters’ superpowers can make fresh. And conversely, as a character drama about a woman who is hiding out in sitcoms to avoid the painful reality of her life, the show feels shallow and evasive, refusing, for most of its run, to dig very deep into Wanda’s pain, or examine the cracks in the world she’s constructed as anything more than clues for the next pulling back of the curtain.

The inimitable Film Crit Hulk posted weekly reviews of the show on his Patreon (and is doing the same with The Falcon and the Winter Soldier), but I particularly recommend his review of the season finale, which goes deep into the way the show constructed its story, and how that construction seemed designed to avoid any forward progression of storytelling in favor of “twists” that were anything but.

From moment one we shoved into the vague scenario with questions: Why are they trapped in a sitcom? What do they know? What do they not know? Who created this scenario? Why? And unlike things with a clear rooting interest, the only thing propelling us through the scenario is our curiosity and a baseline affinity we have for the existing characters. But even though the show is mystery boxing everything, they make an even more crucial mistake of not even treating it like a mystery. As I said so many times, telling a mystery is REALLY HARD. And to even do it properly, you need driving central questions. You need active investigation. You need clever misdirection that not only creates the feelings of twist and turns, but has their own thematic points to make, too. Instead? They settled for constant vaguery. In the end, there was no misdirection. They only teased out the clear answers we implicitly understood as being the only options from the beginning.

Aaron Bady (who isn’t writing that much about pop culture since Game of Thrones ended, so if there’s any reason to be thankful for WandaVision‘s existence, it’s that it brought him out of retirement) has a long piece about WandaVision as a fantasy of 50s suburban domesticity, with an interesting segue into how we’ve all misunderstood Elizabeth Kubler-Ross’s five stages of grief.

The MCU has retconned an explanation for why Wanda would want this white vision of domestic utopia, making her the same kind of sitcom nostalgist as Tobey Maguire’s character in Pleasantville. The old story of the Stark missile that killed her parents now contains the Dick Van Dyke Show playing in the background, and its parables of American postwar opulence, consensus, and stability have been made to directly speak to her Sokovian background. Of course, that background — once a story of Romani twins orphaned by the Holocaust — has been re-rendered in typically pejorative “Third World” caricatures, allowing our Eastern European protagonist to long for the freedom of the free world in more safely clichéd cold war terms (even before Tony Stark drops a missile on her house). Whatever Magneto’s daughter Wanda once wanted, in the comics, her desire and her meaning has been flattened into a cold war vision of iron curtain longing: the America of blue jeans and pop culture, as seen on TV.

Emily VanDerWerff tries to put into words her disappointment with the show’s finale—and particularly the absence of any meaningful consequences for Wanda—by talking about “story karma”.

Mistaking (what the protagonist assumes to be) good motivations for good actions is perhaps the most deeply American thing about Marvel’s cinematic storytelling, and they’ve proved wildly popular worldwide, because all of us can twist any given bad thing we do into a good thing if we think hard enough about all of the reasons we might have done it that aren’t motivated by our own worst qualities. Wanda Maximoff lived under the weight of considerable grief, and in that grief, she did something awful. We’ve all had some version of that in our lives. But that doesn’t excuse our bad actions amid that grief.

That’s why WandaVision’s finale made me finally give up on the idea of the MCU ever understanding the stories it’s trying to tell beyond the most superficial level. Many of these movies are entertaining, but beyond Black Panther (which at least tries to wrestle with the weight of colonialism and the ways in which the affluent have responsibilities to those without) and Guardians of the Galaxy, Vol. 2 (which has a go at talking about legacies of familial abuse), none of them do more than pay lip service to complicated ideas.

Finally, Gerry Canavan looks to no less than Adorno and Edward Said to argue that the MCU has entered its “late period”, in which every new story it produces is only really about what has come before.

‘There is an insistence in late style,’ says Said, ‘not on mere ageing, but on an increasing sense of apartness and exile and anachronism.’ It may well be that the lonely and dyspeptic WandaVision, with its promisingly surreal opening and utterly boring, by-the-numbers finale, will eventually be seen to embody the late style of a franchise that is preoccupied with this sense of being simultaneously before, during, and after its own ending. Late works are about ‘lost totality,’ adds Said; consequently ‘they often give the impression of being unfinished.’ Here, too, WandaVision embodies what I am suggesting will be essential to the late style of the Marvel Cinematic Universe, its metafictional premise abandoned halfway through the run in favour of a perfunctory flashback in episode eight and an even more perfunctory magical duel in episode nine.

Over to you!