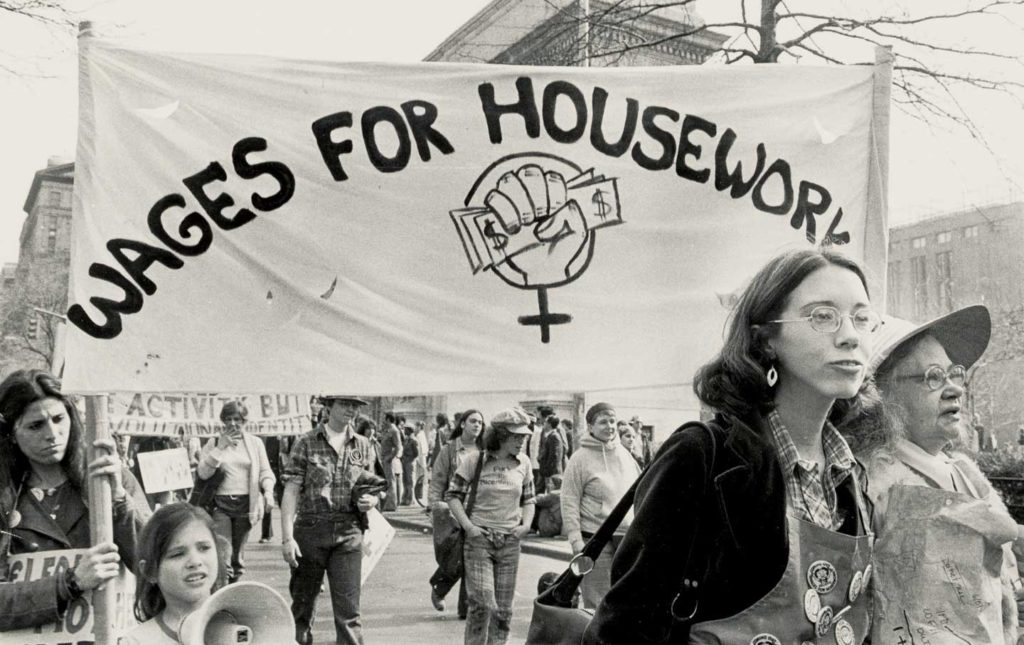

Wages for Housework, Pandemic Edition

A couple of years ago, I reviewed the book of documents that Sylvia Federici, the Italian woman who conceived of and fought for the Wages for Housework movement, put together. Well, Federici is alive and well and fighting for the same issues. So the Times decided to talk to her about what the pandemic lockdown has demonstrated on these issues.

“The commons” denotes resources (land, knowledge, cultural and intellectual material) commonly held outside any kind of market. Commoning is that idea in action, a practice of putting more and more of your life outside the reaches of commodification or extraction. The allure of commoning is that it’s possible anywhere as long as there’s a willing community: An empty lot can become a small subsistence farm, a neighborhood’s health care concerns can be met with a local, neighborhood-run clinic; care work can be shared among families. “You don’t need permission” to common, says David Bollier, longtime scholar of commoning. “You don’t need to have proxies in Washington as lobbyists and lawyers. You don’t have to be an expert — you are an expert of your own dispossession. And therefore, you can devise some of your own things that are situationally appropriate.”

The ways this could look are as various as the communities seeking to address unmet needs. Recently, a group of coders built a free online tool to help families form and schedule child care co-ops. Mutual aid networks are one iteration that has flourished during the pandemic: Using something as simple as a Google Doc, neighbors can write down what they need and what they can give, forming (or revealing) a network of symbiotic relationships. (Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez co-hosted a conference call with the prison abolitionist Mariame Kaba on the basics.) These exchanges often seem mundane: Instead of your hiring a handyman, a neighbor might come to your house to help install your ceiling fan; in exchange, you might help him, or someone else, with his taxes or pet-sitting or garden work. In addition to donating to big nonprofits, you might also reply to calls on your local mutual aid network to help a neighbor make rent. While agitating for the government or other organizations to allocate desperately needed resources, your community might band together to pool and increase the resources it currently has.

Federici’s models for successful commoning are drawn from an internationalist perspective, and she notes that Indigenous communities are frequently originators and keepers of commoning practices: She cites “water defenders” in the Amazon, the Landless People’s Movement in South Africa, urban gardens in Ghana, the Chilean women who pooled their food and labor amid government-mandated austerity programs. “It is not the most industrialized but the most cohesive communities that are able to resist and, in some cases, reverse the privatization tide,” she writes in “Patriarchy of the Wage.”

One of Federici’s most instructive examples of commoning is the protest campaign of the Standing Rock Sioux tribe in 2016 and 2017. In the course of fighting a pipeline project, the tribe and its allies built an encampment network that kept thousands of protesters housed and fed and safe, even as winter descended; they created a school for the children, recognizing that if whole families were going to participate, the children would need both care and education. In part because they made the camps a livable, long-term community, they were able sustain and amplify the effort into a movement with international support and ongoing momentum even though the camp itself was cleared by law enforcement in February 2017.

Federici doesn’t get as much attention or respect as she should, perhaps because her organization never was that big. But she’s a historically important activist and we would be better off as a society at least seriously considering her ideas about housework, community, and togetherness.