How Popular Epidemiology is Both Necessary and Has Significantly Damaged Our COVID Response

This story on a Kansas town that did more than anywhere to promote the polio vaccine now being hopelessly divided on the COVID vaccine is depressing. But it also demonstrates some larger points about popular epidemiology, broadly defined. I’ll comment more on what I mean, but first, the story.

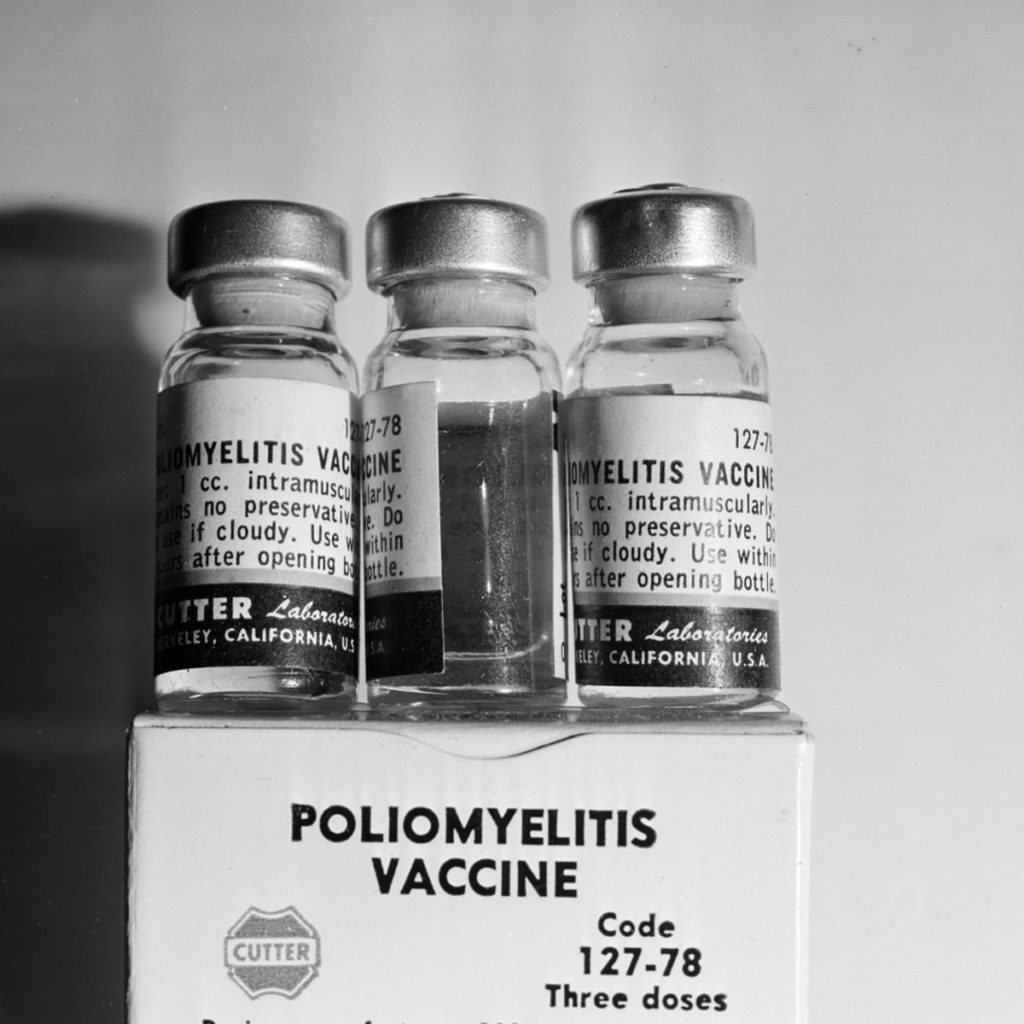

Protection’s “Polio Protection Day” took place on April 2, 1957. Families, many dressed in their Sunday best, lined up in the high school gym to get shots from nurses dressed in starched white uniforms.

That event, sponsored by what was then known as the National Foundation for Infantile Paralysis (now the March of Dimes), received widespread media coverage.

The Herd family was front and center. Herd, his parents and four siblings were chosen to ride on the main float in a celebratory parade, he says, because they looked “average” and because his sister, Cheryl, had survived a bout with polio.

“Mom made us special shirts so we would look good for the occasion,” he says.

Six decades later, the town’s role in kicking off the polio vaccination campaign remains a point of pride memorialized by a small monument in front of the old post office.

“We were an example,” Herd says, “of everybody coming together to try and do something good.”

Stan Herd is two years younger than his brother, Steve. An artist renowned for distinctive crop and landscape works, he now lives in Lawrence, where the University of Kansas is located.

Recalling the event, he says there was no debate about the vaccine or the town’s role in promoting it. Everyone thought: “This is what we’re supposed to do.”

Steve can’t imagine the community coming together in a similar way in 2021.

“Not a chance,” he says. “It would be impossible because we’d all take sides.”

The political fault lines that have complicated national and state efforts to contain the coronavirus run deep in Protection and the surrounding Comanche County. Even with COVID-19 cases rising late last year, county commissioners refused to enforce Democratic Gov. Laura Kelly’s statewide mask order.

“The big difference between 1957 and 2021 is that the polio vaccination event was apolitical. The COVID vaccine has gotten political,” says David Webb, a retired teacher and unofficial local historian, who also participated in the mass vaccination event as a grade schooler.

Now, it’s pretty easy to chalk this up to the radicalization of rural and conservative America thanks to propaganda networks that turn people’s minds into mush. And there’s something to that, of course. On the other hand, think about the anti-vaxxers based in wealthy liberal communities, especially on the west coast, where vaccinations rates are so low even before COVID-19 that old timey illnesses such as whooping cough are making a big comeback.

There’s a much broader problem going on here and it has a complex background. In the 1950s and 1960s, the scientific-technocratic elite of this nation created systems that maximized efficiency through a petrochemical economy. That meant, for example, burning grass fields after harvest to maximize production without thinking of what breathing in smoke would do to people’s health (I am presently doing some writing on this issue in Oregon). It meant engaging in a totalizing spraying regime of pesticides and herbicides, most notoriously DDT, without considering the environmental or human consequences. It was a nation that valued expertise, inherently residing inside a white male wearing a white lab coat. There were good things about that, including the nation’s embrace of the polio vaccine. But the downsides of this soon became quite obvious as well. Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring alerted Americans to the problems with DDT, but there were many other touchstones as well.

As early as the 1950s, some Americans worried what all these chemicals would do to their bodies. There was good reason for that–the science didn’t even test for these things. As late as the 1970s, for instance, workers in plywood mills had to work with chemicals that were completely unlabeled except for the brand name. The right-to-know movement was about creating accountability in the science and technology world while also giving people the power to protect themselves from the chemical world.

A few years ago, I reviewed Andrew Case’s The Organic Profit: Rodale and the Making of Marketplace Environmentalism, for the Journal of American History. It’s a fantastic book that explores the Rodale empire of organic foods and self-health that began in 1942 with J.I. Rodale publishing a new journal Organic Farming and Gardening. This was the pioneering publication of the organic food movement. What Case shows though is that while people had very good reason to worry about what was in their food and the organic movement has been a pretty unalloyed good for society, Rodale also tracked in all sorts of quackery that was outright false or even damaging to people’s bodies. In other words, once you start questioning your food and realizing that you can make better decisions for yourself than the government or the scientists, then what stops you from deciding that you know more than your doctor?

This is the broader issue we face when it comes to health today. In the 1950s, no one questioned the polio vaccine because no one questioned science. Today, science has become deeply politicized. But some extent, that is also the fault of science and technology. We know, despite outrage from Campus Reform fascists and some commenters here when I say this, that science is socially constructed and that when you have scientists not examining their own racism, you produce racist science. This is part of the reason that there is so much distrust of the COVID vaccine in the Black community; the trauma of how the medical community has treated Black bodies throughout history is well-known and well-remembered.

The principle of socially constructed science and technology applies across the board. When you don’t care about how your chemicals might affect human health because the profit motive doesn’t emphasize that, you create a situation where people are going to stop trusting all chemicals, even if out of semi-ignorance on their part. Doctors of course face this all the time, with patients. The popular epidemiology of the 1970s, when, for instance, citizens formed anti-herbicide and pesticide committees and did the investigation of their environmental and health effects that the scientists and the government either refused to investigate or refused to publicize, was absolutely positive. But, again, once you start with that, where do you stop? Now, everything is under question. The impact of that is deeply ambivalent. I don’t see how we get out from under this. When we are in the middle of a global pandemic with amazingly effective vaccines developed in record time, we should be celebrating this side of science while continuing to ask questions about other parts of the scientific world. But for lots of people, it’s easier to either see science itself as an ideology (“Trust Science!”) or to doubt anything out of the science and technology worlds that doesn’t conform with their own existing ideological predilections, whether that’s assuming that every chemical produced is going to attack your body or thinking that a disease is fake news because your beloved fascist president says so.