A Transformed Federal Reserve

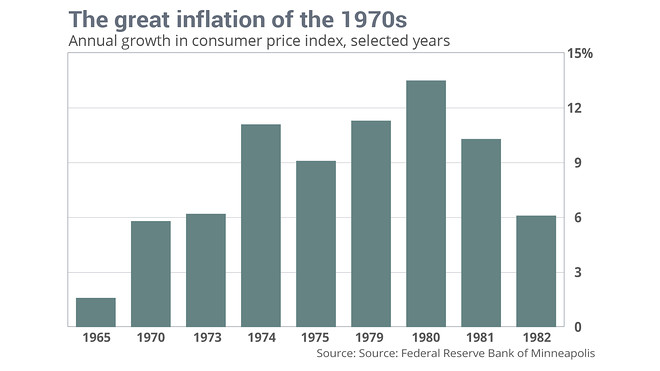

I am not one to dismiss the inflation of the 1970s as a very serious policy problem at the time. Obviously, anyone who lived through that is aware of it. But the lessons of the 1970s have been vastly overlearned by elite economists, who have created a financial policy in the nation with little else in mind for nearly a half-century now. Meanwhile, there are tools to combat inflation that did not exist back then and the global economy is simply an entirely different beast. And yes, the conventional wisdom has remained almost impenetrable about this issue until very recently.

An amusing anecdote about this: When my wife taught at the small college in Pennsylvania that she mercifully is no longer at, she, against what should have been better judgment, dragged me to some horrible party at the president’s house. Somehow, I ended up in a conversation with the president’s wife. And as will happen with me, the economy came up and I started making the argument that we need more inflation because it would help students pay off their debts, not to mention everyone else. The look of horror in her eyes was very palpable. She slowly backed away as if I was arguing in favor of armed robbery or something. It was a great moment.

Anyway, what’s remarkable is that this orthodoxy is finally, mercifully, starting to slip away. Eric Levitz:

This analysis was tendentious at the time, and has become more dubious in the decades since. But the Fed’s decision to de-prioritize full employment both reflected and perpetuated a right turn in American politics that consolidated the new anti-inflationary economic orthodoxy. This would ultimately constrain the ambitions of the Clinton and Obama administrations, with the Fed pressuring the former to slash the deficit, and pursuing premature rate hikes that slowed economic recovery under the latter.

But times have changed — and so has the Fed.

Under Jerome Powell, the central bank has brought American monetary policy into belated alignment with federal law and empirical economics. Instead of attempting to preempt high inflation by sustaining a cushion of unemployment, Powell has waited for inflation to actually show itself before deliberately cooling the economy, a posture he has justified by emphasizing the myriad economic and social benefits of maximizing employment.

As a result, the Fed’s role in America’s fiscal policy debates has flipped. This week, Joe Biden’s $1.9 trillion stimulus plan took on some friendly fire from center-left economists Larry Summers and Olivier Blanchard. While both endorsed the necessity of significant stimulus spending, they suggested that Biden’s package was excessively large, and would risk “overheating” the economy — which is to say, the stimulus would risk injecting more demand into the economy than the nation can satisfy, given the size of its labor force and the productive capacity of its capital stock. And when demand outstrips supply, the result is inflation.

On Wednesday, the Fed effectively intervened in this debate on Biden’s behalf. In remarks to the Economic Club of New York, Powell argued that America’s actual unemployment rate is not 6.3 percent (as official data suggest) but 10 percent, once classification errors are accounted for; that it will take “continued support from both near-term policy and longer-run investments” to restore maximum employment; and that had the pandemic not intervened, there is “every reason to expect that the labor market could have strengthened even further without causing a worrisome increase in inflation.” That last statement is key. Not only does it suggest that Powell believes the U.S. economy can support an unemployment rate significantly below the 3.5 percent we saw in early 2020, the statement also implicitly rebukes the Congressional Budget Office’s official estimate of how much more demand the economy can accommodate without overheating. Which is significant, since Summers built his “overheating” argument around the CBO’s (historically unreliable) estimate of that figure.

The potential of a significant transformation in Fed policy to support real full employment is huge. I mean, it would really change how this nation has run for nearly a half-century now. These policies have worked against labor for a very long time. This is the kind of policy detail that can make one’s eyes glaze over, but as Richard White put it (massive paraphrase here by me) in The Organic Machine, the more boring the agency, the closer you are getting to where the real power lies.