Silicon Valley Organizing

What I find interesting about the rise of organizing in Silicon Valley is that I, perhaps somewhat falsely, identify the tech world as strikingly libertarian. But while I know this is true among our tech overlords, it does not seem to be true among the everyday worker who is simply not seeing themselves as valued workers.

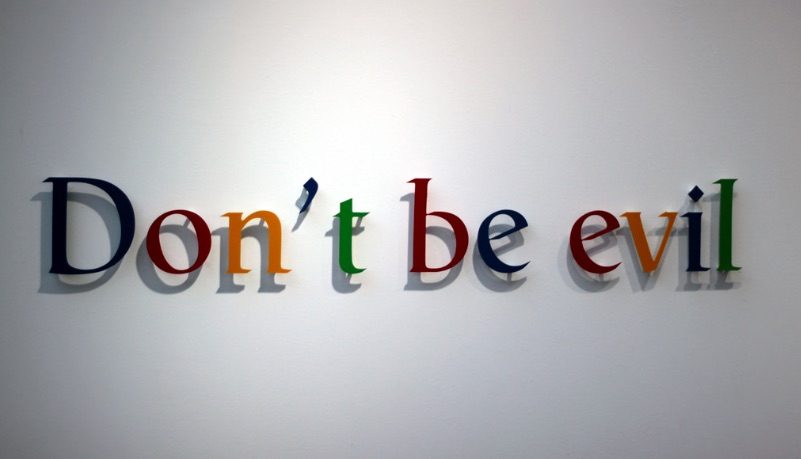

To build and consolidate this power, white-collar tech workers have formed unions of their own. In February 2020, Kickstarter employees voted to unionize in affiliation with the Office and Professional Employees International Union. This month, employees at Alphabet, the parent company of Google, announced the creation of the Alphabet Workers Union, a membership organization to strengthen collective action within the company.

Some tech executives have argued that social issues have no place in the office. Others have argued that tech employees are too privileged to organize. Mike Solana, a venture capitalist, charged that the union’s members were “appropriating the language of exploited coal miners.” In other words, Googlers aren’t real workers; they’re not oppressed enough. Ironically, many people once argued that coal miners were not real workers, because they were not directly supervised and often owned their own tools and hired their own helpers.

These criticisms are understandable. The decades-long decline of the labor movement has left it so weak that many Americans know little about its history. In fact, workers have often organized not only to improve their wages, but also to gain more control over their work — especially when it had an outsize effect on the world. In the 1970s, employees at Polaroid and IBM, two major tech firms of their day, protested their companies’ business with South Africa’s government while it enforced apartheid.

The suggestion that people who work at tech companies are too privileged to organize also seems dubious. Alphabet Workers Union membership, for instance, includes contractors who do not enjoy the high salaries or generous benefits of senior software engineers. And even better-compensated tech workers routinely experience racism and sexism. Is it a privilege not to be insulted or assaulted at work? Studies show that harassment both reflects and reproduces inequality, by preventing victims from seeking promotions and raises, if not pushing them out of the company altogether.

Critics of the tech worker movement also imply that collective action is suitable only for the most immiserated workers. But organizing can help protect people against many kinds of harm, especially in a country where most people can be fired at any time for almost any reason. Indeed, about a month before the Alphabet union launched, Timnit Gebru, a high-profile Black woman computer scientist who helped lead Google’s ethical-artificial-intelligence team, said the company fired her for being too critical of its hiring practices and the biases built into artificial intelligence systems.

Yeah, I mean, the idea that social issues have no place in unions is totally ridiculous. Workers can organize around whatever they want. It’s what motivates them to collective action that matters, not a set of limited issues that reflects the history of the labor movement. Arguably, organized labor has had too narrow of a range of issues it worked from, limiting its playbook. In any case, workers can do whatever they want if they have the organizing and strategy to make it happen. As for whether these are “real” workers, this is the most tiresome debate ever. The idea of who and who is not a real worker is something that the media regularly indulges in when they pay far more attention to coal miners and steel workers than industries with vastly more employees. Anyone who works for wages or salary is a worker and that certainly includes Silicon Valley tech workers, teachers, professors, office workers, and so many other white collar laborers.