Erik Visits an American Grave, Part 752

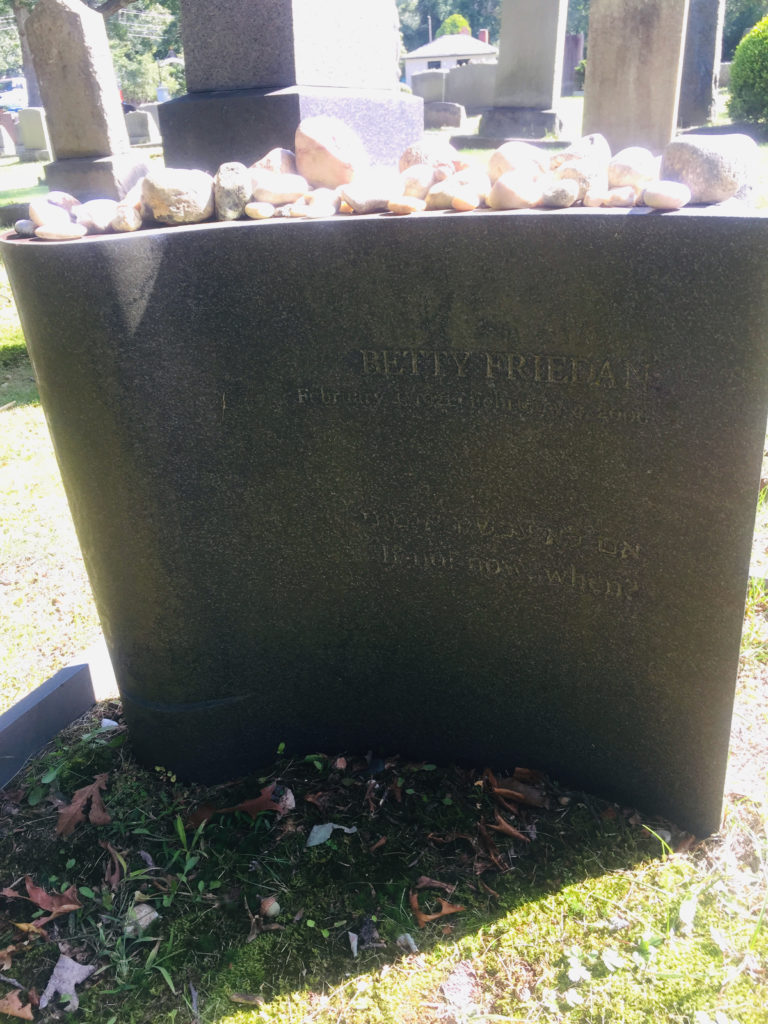

This is the grave of Betty Friedan.

Born in 1921 in Peoria, Illinois, Bettye Goldstein grew up in a Jewish immigrant family. Her father was a jeweler and her mother worked for a local newspaper, writing the society page. That mostly happened after Friedan’s father fell ill. Betty later said that her mother seemed happier when she was working more, an influence on her daughter.

Friedan became interested in Marxism as a girl. She was a star student and went to Smith College, graduating in 1942 as a psychology major and after being the editor-in-chief of the college newspaper. At Smith, she was sharply anti-militarist and even published op-eds against the U.S. joining World War II. She went to Berkeley for a year upon graduation to study psychology with Erik Erikson. But she had a jerk of a boyfriend who convinced her that it would be a waste of time for her to get a Ph.D. She later used that as motivation in her work for feminism.

Instead, Friedan became a newspaper reporter for various leftist organizations, including communist-led unions. She wrote for the United Electric Workers newspaper for six years, between 1946 and 1952, as that union was being evicted from the CIO for its communism. Among her work for UE was writing pamphlets demanding equal rights at work for women. She was eventually fired when she got pregnant for the second time. Never let it be said that communism had a progressive gender ideology. She married a man named Carl Friedan in 1947 and changed her name, staying married to him until 1969. She still wrote though, freelancing for many magazines, including Cosmopolitan.

Friedan also started writing a book. It was 1957. She had graduated from Smith 15 years earlier. She had something of a career, but she was mostly taking care of her kids in their Rockland County home, despite her freelancing. Her fellow Smith graduates were even more alienated than she was. They were staying at home with the kids, not using their fantastic education. They went from their years after graduation living the good life in New York and Boston to being isolated in suburban homes with 4 year old kids. And yes, many responded to this with booze and pills. Friedan began to write articles about “The problem that has no name,” which was telling in that no one had even paused to think about this issue before. This was also increasingly her own life. Her marriage was tempestuous, evidently to the point of occasional, though not routine, physical violence. She was not happy.

These articles laid the groundwork for Friedan’s 1963 book The Feminine Mystique. One of the most important books written in American history, it rightfully can be called the root of second wave feminism and the women’s movement that became a huge part of American life by 1970. The book’s conclusions seem utterly uncontroversial today: women were just as capable as men to do anything in society, staying at home was a waste of women’s talents and was bad for them mentally, that sexism was a centerpiece of American society. And yet, this was hugely controversial in 1963. Moreover, plenty of people, men and women, have not accepted its conclusions today and pursue policies to place women right back in the home, to pay them less for the same work, to ensure that they do not have the right to control their own bodies.

The Feminine Mystique had an immediate impact, touching the lives of many women, particularly the well-off white reading public demographic among them. And so, in 1966, Friedan and others built on this work by founding the National Organization of Women. She and others were furious at the poor job the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission had done in enforcing gender equality since the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. Friedan and Pauli Murray, one of the most underrated heroes of American history, wrote the group’s manifesto. They fought hard and had some early victories, including getting an executive order expanding affirmative action programs to women in 1967 and a 1968 EEOC ruling banning gender-exclusive employment advertisements. In 1969, Friedan helped found the National Association for the Repeal of Abortion Laws, today just known as NARAL, which has been a major force in protecting women’s access to abortion since Roe v. Wade in 1973.

In 1970, Friedan, going back to her labor past, organized the Women’s Strike for Equality, which did not really revolve around women’s work as much as Friedan had hoped it would. That same year, she helped lead the fight against Harold Carswell’s appointment to the Supreme Court by Nixon because of his opposition to the Civil Rights Act. This was successful. Of course, she was passionate about abortion rights and made this a central plank of NOW, even as this made some allies uncomfortable. In 1971, she, along with other leading feminists such as Gloria Steinem, Shirley Chisholm, and Bella Abzug, founded the National Women’s Political Caucus. Less successful was the Equal Rights Amendment. It’s amazing to think that this obviously needed constitutional amendment would not be ratified, but the rise of backlash politics in the later 1970s doomed it at the last second thanks to the work of the odious Phyllis Schlafly, among others.

Now, we do need to discuss Friedan’s opposition to lesbianism. It was a reactionary position and plenty of people called her out on that at the time. The so-called “Lavender Menace” was a combination of homophobia and fears of older leftists who had lived through McCarthyism as to what would happen if seemingly radical positions came to dominate the women’s movement. She was wrong. It does bruise her legacy. It does not repudiate it. Her own position on this changed over time, though one could never really call her an activists for lesbian equality. However, she did second a resolution for lesbian rights at the 1977 National Women’s Conference, though more so she could move on to what she considered more important issues and not fight over something she more indifferent about than outright opposed to.

Friedan did not unite with the anti-pornography side of the feminist movement, considering any repression of images a violation of freedom of speech that was more damaging than the pornography itself. She spent much of the 1980s and 1990s teaching at UCLA and NYU and writing more articles and books.

Friedan was also well known for being a difficult person. Many called her abrasive and while that could be chalked up to sexism, it was also a lot of other feminists, including close allies, who said this about her. She wrote in her own autobiography, “The truth is that I’ve always been a bad-tempered bitch. Some people say that I have mellowed some. I don’t know….”

Friedan stayed active in feminist politics for the rest of her life, dying of congestive heart failure in 2006, the day she turned 85.

Betty Friedan is buried in Sag Harbor Jewish Cemetery, Sag Harbor, New York. Sorry for the low quality of the picture. The sun was shining right on it. I took a bunch of pictures with different settings, but I don’t know how to do this very well (as is evident by now!) and this is the best one.

This grave visit was sponsored by LGM reader contributions. Many thanks! I know this is exactly the kind of grave visit many of you want to see. If you would like this series to visit more American feminists, you can donate to cover the required expenses here. Pauli Murray is in Brooklyn and Virginia Louisa Minor is in St. Louis. Previous posts in this series are archived here.