Remember the Pueblo Revolt

Our racial and racist past is much more than just a Black struggle. It’s a struggle of many racial minority groups that depend a great deal on where you are at. And yet, in the U.S., our popular history mostly reduces all of this to a Black-White struggle. But if you are, say, in New Mexico and you are fighting for a racial justice against an incredibly racist and violent Albuquerque Police Department, for instance, your historical touchstones are likely to be different than in Louisville or Baltimore. And this brings us to the Pueblo Revolt, merely the most successful Native revolt in American history and one that hardly anyone outside of the Southwest has even heard of.

While protests over police violence against African-Americans spread from one city to the next in the aftermath of George Floyd’s killing in May, the missive scrawled in red paint on the New Mexico History Museum reached further back in time: “1680 Land Back.”

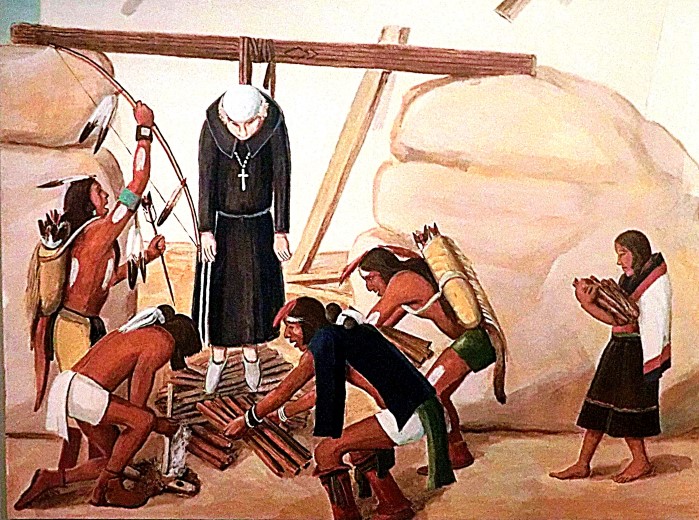

The graffiti invoked another rebellious juncture in what is now the United States: the uprising in 1680 when Pueblo Indians handed Spain one of its bloodiest defeats anywhere in its vast colonial empire. From the protests in the late spring against New Mexico’s conquistador monuments to the writing last month emblazoning the walls of Santa Fe and Taos celebrating the Pueblo Revolt, the meticulously orchestrated rebellion that exploded 340 years ago is resonating once again.

The increasingly energetic activism in New Mexico points to how the protests across the country over racial injustice and police treatment of African-Americans have fueled an even broader questioning about the racism and inequality that endure in this part of the West.

Indigenous groups are referring to the Pueblo Revolt in organizing drives over such issues as stolen lands, the Justice Department’s deployment of federal agents to Albuquerque and the Trump administration’s handling of the coronavirus pandemic, which has hit Native peoples especially hard.

“The Pueblo Revolt was the most successful Indian revolution in what is now the United States,” said Porter Swentzell, a historian from Santa Clara Pueblo, one of New Mexico’s 23 tribal nations. “Twenty twenty is energizing this upsurge of activism inspired by the revolt that was building for years.”

In recent decades, commemorations of 1680 in New Mexico and Arizona were already challenging the traditional centering of early American history on the English colonies in Plymouth or Jamestown. Now Representative Deb Haaland, a member of New Mexico’s Laguna Pueblo who is one of the first Native American women elected to Congress, is among the prominent figures raising awareness about the Pueblo Revolt.

The Pueblo Revolt is as important to American history as Nat Turner’s rebellion, the Stonewall Riot, the actions of Harriet Tubman, the Montgomery Bus Boycott, the passage of the Nineteenth Amendment, and so many other touchstones on the history toward justice and freedom. Moreover, the Pueblo Revolt actually succeeded in kicking the Spanish out for 12 years and when the Spanish returned, it was in a less intensely exploitative way. And if you are Hopi, you escaped any European domination for a mere 160 years, until the Americans arrived after 1846, though even here they were part of the maelstrom of slavery and war unleashed in the Southwest by competing Native and European powers around it. Like so many stories of Native history, the Pueblo Revolt needs to play a much greater part in our historical memory than it does and that very much includes in the politicized historical memories of liberals and the left.