Erik Visits an American Grave, Part 687

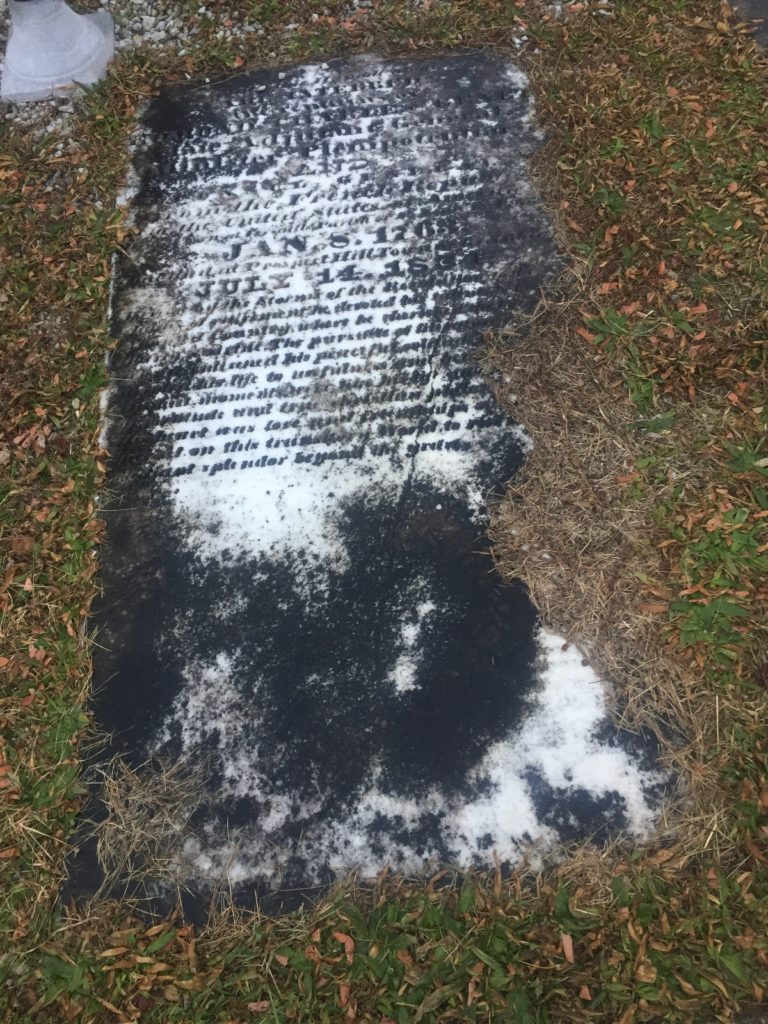

This is the grave of Edmond Genêt.

Born in 1763 in Versallies, France, Edmond-Charles Genêt was the son of a civil servant, head clerk in Louis XV’s ministry of foreign affairs. A brilliant young man, he was something of a savant at languages, able to read Latin, Greek, English, Spanish, Italian, Swedish and of course French by the time he was 12. He was thus appointed court translator in 1781, when he turned 18. He rose rapidly in the French foreign affairs world, being named ambassador to Russia in 1788, only 25 years old. But the young man was also an Enlightenment thinker who came to despise all monarchies, both at home and in Russia. Sympathetic to the French Revolution, the new government left him there until 1792 when Catherine the Great kicked him out because he was supporting anti-monarchy forces in St. Petersburg.

Still very useful to the Girondists, Genêt was sent to the United States. This was more his speed. But he was arrogant and made a massive error. From the moment he entered the United States, he attempted to intervene in American politics. The young nation’s politics was divided by the battles between Britain and France in the aftermath of the French Revolution. The Federalists were pro-British and the Jeffersonians pro-French. Both sides had their reasons–ideology and economic. Rather than go to Philadelphia to present himself to President Washington, Genêt instead sailed to Charleston and then began a campaign north rallying the South to the French flag. He wanted to get American privateers to join the fight against the British. Plenty were ready to in the South. He raised a militia to fight English forces in Florida, which briefly had taken the territory from Spain. He even tried to start quasi-revolutionary Democratic-Republican societies to push the French cause.

To say the least, Genêt overstepped his bounds. Washington and Alexander Hamilton were furious. The last thing they wanted was the U.S. to get caught up in the wars after the French Revolution, especially if that meant supporting France. Even Thomas Jefferson was highly embarrassed and found Genêt basically indefensible. In fact, Genêt was the only thing that could get Jefferson, Hamilton, and Washington to agree on anything by 1793, as the first two helped Washington write an 8,000 word letter of criticism to Genêt and then sent a letter to Paris denouncing him and demanding his recall.

Meanwhile, life was moving fast in Paris. The Jacobins were now in charge. They were happy to bring Genêt back because they wanted to guillotine him. Genêt was no idiot. He knew what he faced if he returned to France. So he begged Washington, after basically insulting him on his tour, to allow him to stay in the U.S. Feeling bad for him, Hamilton, Jefferson, and Washington agreed.

Genêt went on to live the life of a well off New York farmer. He married the daughter of George Clinton and mostly stayed out of politics. The only time he really became active was in 1807, when he attacked James Madison for being a pawn on Napoleon in order to promote Clinton’s presidential chances. Somewhat hilariously, he was now promoting the New England line against the Virginia Dynasty. It didn’t work and of course Madison replaced Jefferson in 1809. Genêt also engaged in tinkering and wrote a book on inventions. When Clinton’s daughter died, he married the daughter of the nation’s first postmaster general. He died in 1834, having never returned to France I believe.

Edmond Genêt is buried in East Greenbush Cemetery, East Greenbush, New York.

This post was sponsored by LGM reader donations. Many thanks as always!!! If you would like this series to visit other figures of the Early Republic, you can donate to cover the required expenses here. John Jay is buried in Rye, New York and Henry Knox is in Thomaston, Maine. Previous posts in this series are archived here.