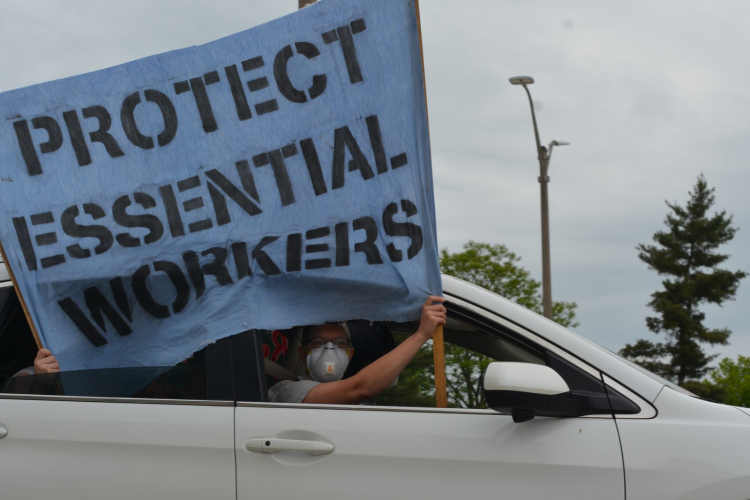

How Are Our “Essential Workers” Doing?

In the era of COVID, we have defined “essential worker” as “someone we don’t mind dying for us, but hey you’re a hero!” Many of those essential workers are poor, many of them are people of color, many of them are immigrants. Some are refugees resettled in the United States. And in Iowa, the combination of working in dangerous conditions, specifically COVID-dangerous workplaces such as supermarkets, disease, and now a derecho has really placed a whole group of refugee “essential workers” in a precarious situation.

A Congolese refugee who found a new home in Iowa’s second-largest city, Safari and his family have been displaced once again by the derecho storm, his former apartment among the more than 1,000 buildings made “unsafe to occupy” after being essentially annihilated by the high winds. Like many of the apartment complex’s former residents, the family stayed in a tent until they were able to move into a hotel on August 15, nearly a week after their home had been destroyed.

Safari works at a nearby Walmart in a position deemed “essential” throughout the pandemic; COVID-19 has killed more than 1,000 people in a state with a population of just over 3 million people. After dealing with coronavirus concerns, the sudden winds of destruction were just another blow in an already dangerous year.

“We have corona and then this also, that’s a bigger problem for us,” Safari said.

The derecho destroyed an estimated 43 percent of Iowa’s crops, half of Cedar Rapids’ tree canopy, and at least 64,000 people were without electricity at one point. More than 200 refugees—hailing from Pacific island nations, the Democratic Republic of Congo, and other African countries—were forced from their homes by the collapse of several apartment complexes.

While the city of Cedar Rapids attempted to crawl out from beneath the decimation and the state slowly responded, many of these refugees were forced to live grouped together in tents and makeshift shelters just outside of their former homes. Some were able to cook, barbecuing chicken wings and ribs over makeshift grills made from spare parts and biding time while waiting for the city and aid organizations to assist in temporary relocation. World Central Kitchen arrived and began serving meals to the displaced while they waited to see what would happen next. In the meantime, workers like Safari were expected to continue on at their jobs.

“It’s very difficult to go to work, with my family. But I try, I try,” he said.

But hey, thanks for your service in risking your life everyday so I can eat whatever I want whenever I want.

I can’t really blame Iowa per se for its response to the derecho–after all, that’s a hell of a thing to deal with. But it is indicative of an overall situation of who suffers the most in any given natural disaster, whether it is pandemic, hurricane, tornado, or derecho.