Erik Visits an American Grave, Part 670

This is the grave of Lewis Hine.

Born in 1874 in Oshkosh, Wisconsin, Hine was middle class but suffered through his father dying in an accident when the boy was a child. But Hine was a skilled student and studied sociology at the University of Chicago, Columbia, and NYU. He was also fascinated with photography. A Progressive, he became interested in using his photographic and sociological skills together to make change. He got a teaching job at the Ethical Cultural School, an elite Manhattan school and began taking his students to Ellis Island to take pictures of the arriving immigrants. Hine began selling these images, mostly to the Progressive magazines Charities and the Commons and Survey.

Hine’s photographs began to get the attention of other social agencies. In 1907, he became the official photographer of the Russell Sage Foundation and was the main photographer for its The Pittsburgh Survey, the pioneering sociological study of that industrial city. That project included a lot of leading Progressives such as the economist John Commons, the socialist Crystal Eastman, and the social investigator Elizabeth Beardsley Butler.

The next year, the National Child Labor Committee hired Hine as its chief photographer. He traveled the nation taking the pictures of children at work that made his work famous, attempting to move the public to outlaw child labor. He did not succeed on a national level until the Fair Labor Standards Act in 1938, but the images were powerful and outraged a lot of people against child labor. Several states began to pass child labor legislation during these years, in large part thanks to Hine. He published his photos in books such as Child Labor in the Carolinas and Day Laborers Before Their Time, both published in 1909. Hine took a lot of risks here. You think these factory owners wanted him in there? No way. He was threatened with violence for his pictures. He often came up with some kind of ruse to get the bosses to let him in. Maybe he was a fire inspector, maybe a postcard salesman (in an era where people actually sent postcards of lynching in the mail, this could actually work). Moreover, in an era where lots of reformers worried about children working in mills and mines, Hine also tried to bring attention to street kids in cities struggling through selling newspapers. He was basically competing with the boostrapism of Horatio Alger here, a myth that Americans have long desperately wanted to believe, and these images did not receive the same attention as his work in the factories, but to Hine and the NCLC, this was just as important an issue.

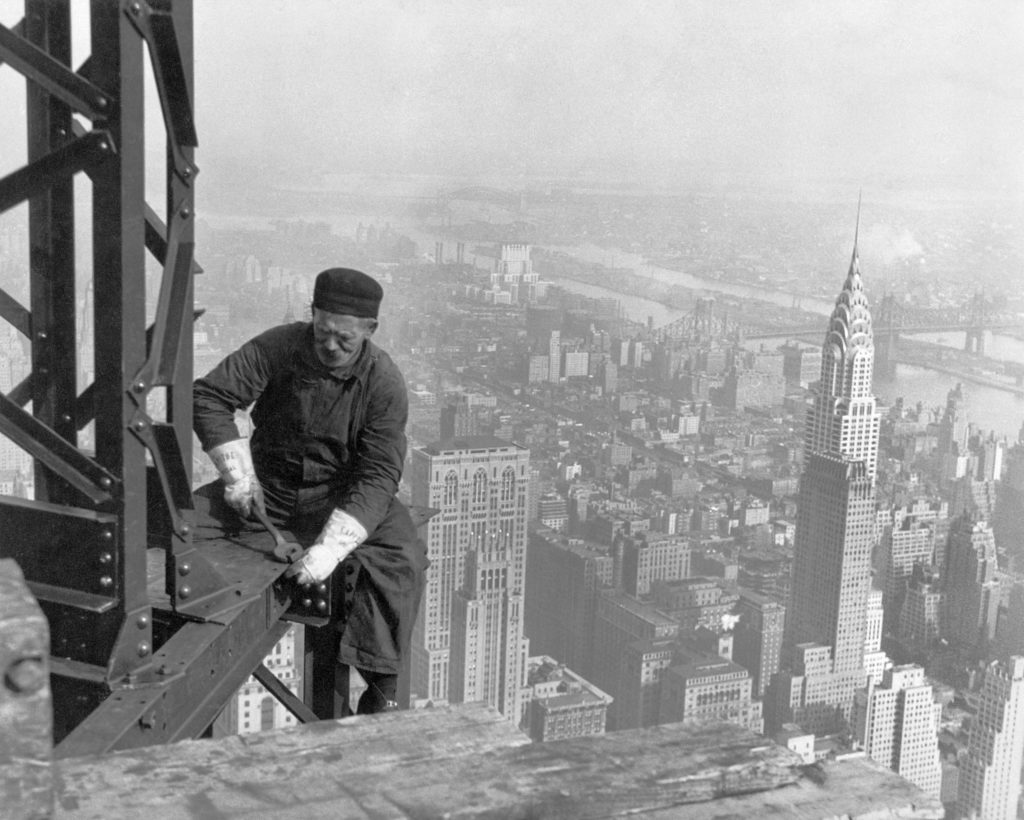

The Red Cross brought Hine on during World War I to photograph relief work in Europe. He published a photo book titled The Children’s Burden in the Balkans in 1919, based on this work. He took a lot of labor pictures in the 1920s, including of women in the household, and then the Empire State Building’s owners brought him on to take pictures of the workers laboring to make that immense skyscraper in 1930. In that, he worked in this crazy basket on a string that was hung 1,000 feet over Fifth Avenue. He published Men at Work in 1932 based on these pictures. The Great Depression saw him back with the Red Cross for awhile and then with the Tennessee Valley Authority once the New Deal started.

In 1936, Hine became the chief photographer of the Works Progress Administration’s National Research Project. But his work there did not go well. Whether he made someone mad or his work was declining as he aged, I don’t know. But for as famous as Hine had become with his photographs, he either never made much money on them or he frittered it away. He was let go from the WPA and was pretty desperate. He repeated wrote to Farm Security Administration head Roy Stryker to get let on to the FSA’s now famous photography projects, but Stryker consistently refused to hire him. Some have speculated that this was because of his outright refusal to give up rights to his photographs. Hine was by now outright poor and had to go on welfare programs at the end of his life after he lost his house. Just before his death, art critics approached him about a retrospective, which had never happened for him before. But he died after an operation in 1940, aged 66. Hine became much more famous after his death than he was through much of his life.

Let’s take a look at some of Hine’s amazing work.

Lewis Hine is buried in Ouelout Valley Cemetery, Franklin, New York.

This grave visit was sponsored by LGM reader donations. Many thanks! If you would like this series to visit other American photographers, you can donate to cover the required expenses here. Unfortunately, an enormous percentage of the nation’s most famous photographers were cremated or have unknown grave sites. Robert Capa is in Amawalk, New York and Garry Winogrand is in Fairview, New Jersey. Previous posts in this series are archived here.