This Day in Labor History: July 7, 1903

On July 7, 1903, Mary “Mother” Jones launched the Children’s Crusade in support of a Philadelphia textile strike and to raise awareness about the need to end child labor. Marching to President Theodore Roosevelt’s home on Long Island, Jones intended on pressuring the supposedly reformist president into taking action. But he would not.

Child labor had been central to the American workforce since the beginning of the Industrial Revolution, especially in the textile industry. While the technology of textiles had changed dramatically in the century after this, the basic labor strategy had not. Employers sought the lowest paid labor and whenever they could, that included children. States such as Alabama repealed their child labor laws just to attract New England-based textile firms avoiding unions. After 1900, this became a much larger part of the fight for change, both from organized labor and from Progressives such as Florence Kelley and the National Consumers League.

Although already an aging woman (though one who added ten years or so to her age to make her seem older than she was) Mother Jones was still relatively early in her activist career. Known as Mother Jones by 1897, she had become a direct action force providing critical moral and organizing support for the nation’s fighting workers. She also had a great feel for the theatrical.

Philadelphia was a major home for textile factories at this time and they were concentrated in the Kensington area. In 1903, 46,000 workers went on strike, the largest strike in the city’s history to that time. They had several demands, including a reduction in hours to 55 per week and the end to night shifts for women and children. Some of the children working in these factories were only 10 years old, even though Pennsylvania had a law on the books that did not allow children under 13 to work. As was so frequent in this era, even if state did pass a law, it went largely or completely unenforced.

The strike was large and had grabbed the attention of labor leaders such as Eugene Debs and had significant local support from Progressives, including several leading ministers, it struggled to get much attention from the city’s newspapers. See, the textile owners were close to the newspaper owners and sometimes shareholders in the papers. They didn’t report on the child labor issue at all. Meanwhile, Jones came to town to lend support. Finding out about this problem, she stated, “I’ve got stock in these little children, and I’ll arrange a little publicity.”

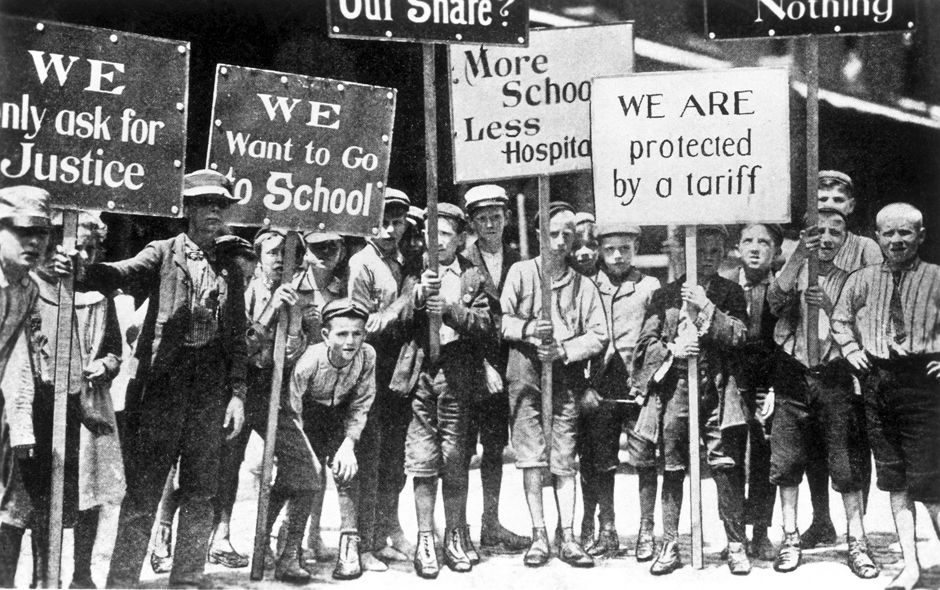

She sure did. She arrived on June 15. On June 17, she led a march of maimed and broken children through the streets of Philadelphia. The kids held signs that read things such as “We Want to Go to School” and “A Full Dinner Pail and an Hour to Empty It.” It went well. At a later rally, she announced what became known as the Children’s Crusade. She would gather the children for a public march against child labor. Many of their parents joined them as well. The initial idea was to march just to New York City, 100 miles, which is a very long march for children. But then she realized that targeting Roosevelt specifically would gain even more publicity.

The Children’s Crusade was a tough time. It was summer and hot. Many of the children dropped out. It almost fell apart immediately because no one had any money to pay the toll to walk across a bridge crossing the Delaware River into New Jersey! But it did great at gaining publicity. There were big rallies throughout the New Jersey industrial cities, some of which with thousands of people in attendance, that not only gained the cause publicity but also raised much needed money for the strikers and for that matter just to pay for the march.

Jones, who gave a great speech, spellbound her listeners in New Jersey with her many talks. She would also directly challenge the manhood of laborers who did not contribute to the cause financially. One night, fleeing the rain, they by chance took shelter in the barn at Grover Cleveland’s house, who was away on vacation. It took them 16 days to reach New York City. On July 23, they marched into the city, with sixty people left. They had a parade up Second Avenue. They stayed in New York awhile to keep up the pressure. On July 26, they all went to Coney Island where Jones had arranged for all the children to be locked in cages and put on public display to demonstrate how the bosses acted toward the workers. Moreover, many of the children were actually maimed already through the dangerous work they did. Showing their broken bodies to the public that could so easily just ignore reality since they didn’t see was tremendously powerful.

Then Jones and the children went on to Sagamore Bay, where Roosevelt had his Long Island home. This was the end of the march and it was anticlimatic. Roosevelt simply refused to meet with them at all and his secretary served as a buffer so they never saw each other. Moreover, as was so common, the strikers simply couldn’t hold out long enough to see the publicity through. By this time, many of them were already heading back to work. The strike soon fell apart entirely.

But it would be inaccurate to say that the protest didn’t have positive consequences, even as the initial goal was lost. This happens in many protest movements, very much including Occupy Wall Street for example. The Children’s Crusade absolutely did make a lot of people aware of the horrible problems with child labor. Jones certainly believed it had been successful ultimately, as she wrote in her autobiography published late in her long life. In 1905, the state of Pennsylvania passed a new child labor bill that moved the ball forward for that state. Congress passed the Keating-Owen Child Labor Act in 1916, but the typically reactionary Supreme Court overturned it in 1918. In 1924, Congress sent a Child Labor Amendment to the states for ratification to the Constitution. It has still not been ratified, but it could be and should be. Much child labor was finally eliminated in the Fair Labor Standards Act, with exceptions in areas such as child labor that still impact children in the United States today, such as the tobacco fields of North Carolina. Also, child labor still makes our clothing. But it’s overseas, so we basically don’t care and don’t do anything about it.

Some of the details in this post came from C.K. McFarland’s 1971 article in Pennsylvania History titled “Crusade for Child Laborers: ‘Mother’ Jones and the March of the Mill Children.”

This is the 361st post in this series. Previous posts are archived here.