This Day in Labor History: July 31, 1905

On July 31, 1905, Matumbi tribesman in German East Africa (today, mostly Tanzania, or Tanganyika as it was known then) marched on the trading post of Samanga, burning cotton fields and the trading post itself. This was the beginning of the Maji-Maji Rebellion, one of the most important moments of resistance to the European colonization of Africa and the labor regimes placed upon Africans during this era.

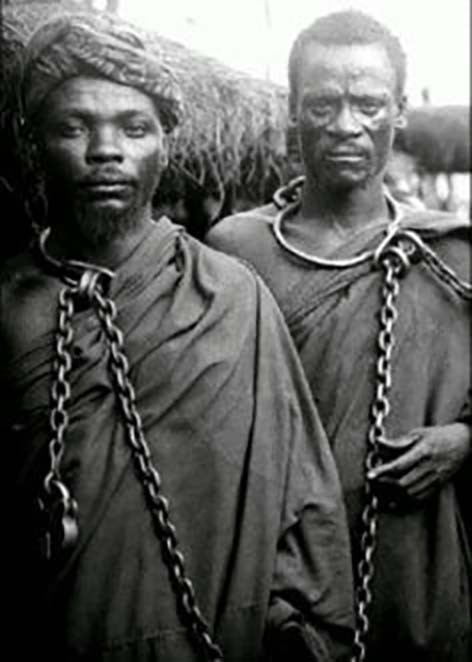

Colonization wasn’t just a battle for prestige in Europe. The point of it was to force colonized people to labor for the profit of the colonizing power. One of the major crops, especially for the Germans, was cotton. They wanted to have a cotton culture that competed with the United States and what Britain had created in India and Egypt. To achieve that, the German colonizers used force. The Germans never really relied on a soft touch for colonization. Forced labor was central to their approach, in part because the German government did not have a large presence on the ground. They also engaged in an official policy of murdering tribal kings to undermine any resistance they might face after they took Tanganyika in 1898. Chain gangs were already common by 1900 to enforce discipline. Racism and violence went together hand in hand.

In 1902, the Germans demanded that the people of German East Africa grow cotton for export. The attempt to turn the tribes of the area into a rural proletariat like the U.S. had in the South was always going to lead to heavy resistance for these newly colonized people. Each village was given a quota of cotton to produce and it was left up to the village headman to manage it. But like the rest of colonization, most of the tribes hated the idea of wage labor, an insult to them and something also completely foreign. So they resisted it in any way they could. The Germans had also instituted rubber market and since there was wild rubber in the area, this was a way that some of the tribes could resist the cotton economy. So the Germans banned the cultivation and collection of rubber in 1904.

All of this, like the rest of colonization, totally transformed the lives of the affected people. That’s not only because they were now growing cotton, but because the Germans forced the men to do so much of the forced labor, it changed gender roles as women had to take on traditional roles of men. Moreover, this labor regime that required new people to come to these plantations also was seen by tribal men as increasing the chances of adultery, infuriating them.

These were societies that largely existed as self-sufficient producers, though of course with some trade. But the ability to exist in that traditional state of self-sufficiency became next to impossible under German rule. Moreover, the cotton regime was close to slave labor, as the workers received only minimal compensation for growing the fiber the Germans demanded. What did the Germans use to enforce this? The lash. For many of the affected peoples, death through fighting was preferable to life growing cotton. The Germans had actually borrowed the enforced growing of cotton from its colony in Togo, which in itself had paid for Black advisers from Booker T. Washington’s Tuskegee Institute to implement in that colony a few years before. Yes, Booker T. Washington was partially responsible for recreating the horrible conditions of the Jim Crow South in Africa.

The harsh labor regime and bitterness over the forced changes in gender roles combined with a drought in 1905 to bring things to a head. A spirit healer named Kinjikitile Ngwale became prominent. He provided an apocalyptic religious message that said the people of the region were destined to rid the area of the Germans if they rose up against them. The followers of Bokero, as he then became known, took a war medicine made up of water, castor oil, and millet seeds that was to make German bullets turn into water.

On July 31, the Maji-Maji Rebellion began with Bokero’s followers destroying cotton plants and that trading post. Bokero was immediately captured and executed, but this did not end the rebellion, not by a long shot. This had started with the Matumbi people, but the Ngindo joined in quickly, massacring a party of five missionaries. Then the Yao tribes joined up, the rebels took to the hills, and began attacking German forts. The Qadriyya Brotherhood declared jihad against the Germans as well, as the region’s version of Islam and the tribal religions often commingled. But even though the Germans had few people, their overwhelming military superiority, including machine guns, meant that Africans were massacred in large numbers.

Still, there was so much anger at the new labor regime the Germans had created in German East Africa that more tribes revolted. This included the Ngoni, with 5,000 men. But with a huge massacre of maybe 1,000 Ngoni on October 21, the Maji-Maji Rebellion mostly fell apart. But by this time, the Germans, who had sent reinforcements in from other colonies, were not content with letting it go. They wanted to discipline their labor force. So they went on the offensive. A hastily put together army moved south, destroying villages and crops and undermining any self-sufficiency that would allow the tribes to escape the cotton labor regime. As fighting continued into 1906, the Germans chose famine as their key strategy, starving out any remaining rebels. It took until August 1907 for the last remnants of the rebellion to give up.

The total dead from the Maji-Maji Rebellion was 15 Europeans, 389 African soldiers in the German Army, and maybe 75,000 fighters from the tribes and upwards of 175,000 civilians killed by the famine. The Germans would have their cotton production at any price.

This is the 365th post in this series. Previous posts are archived here.