Neil Gorsuch Cancels Andrew Jackson

While it got relatively less attention than the Trump tax cases, by far the most important ruling handed down by the Supreme Court yesterday was McGirt v. Oklahoma. The quality of the arguments in the principal dissent (Roberts) and the majority opinion (Gorsuch, joined by the Court’s four liberals) represent a mismatch of the first magnitude. Gorsuch owns Roberts as thoroughly as Kagan owned Roberts in Rucho, only it’s much more satisfying because his opinion was speaking for the Court.

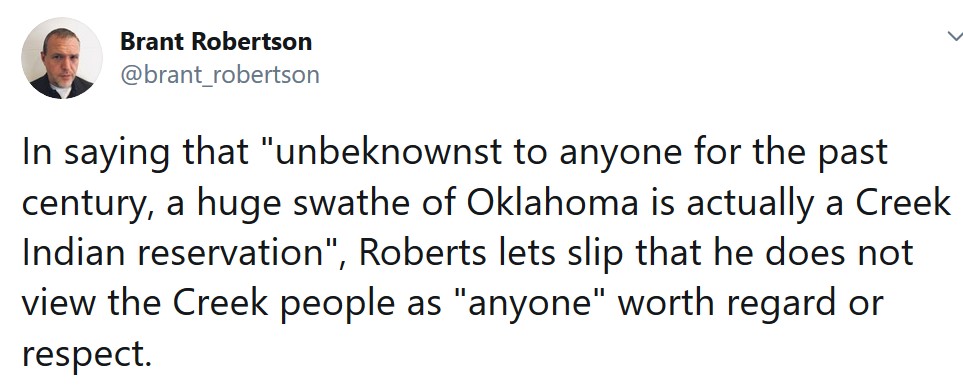

The way Roberts begins his dissent is a massive tell:

In 1997, the State of Oklahoma convicted petitioner Jimcy McGirt of molesting, raping, and forcibly sodomizing a four-year-old girl, his wife’s granddaughter. McGirt was sentenced to 1,000 years plus life in prison. Today, the Court holds that Oklahoma lacked jurisdiction to prosecute McGirt—on the improbable ground that, unbeknownst to anyone for the past century, a huge swathe of Oklahoma is actually a Creek Indian reservation, on which the State may not prosecute serious crimes committed by Indians like McGirt. Not only does the Court discover a Creek reservation that spans three million acres and includes most of the city of Tulsa, but the Court’s reasoning portends that there are four more such reservations in Oklahoma. The rediscovered reservations encompass the entire eastern half of the State—19 million acres that are home to 1.8 million people, only 10%–15% of whom are Indians.

Whenever an opinion denying a claim of civil liberty demagogically starts off with a graphic depiction of the crime, implying that the majority ruled as it did because it’s soft on forcible child sodomy, the likelihood that the opinion is feeble on the merits is very high. And this is certainly no exception. It’s the judicial equivalent of pounding the table when you have neither law nor facts on your side. The move is particularly ridiculous in this case because the result of the holding isn’t that McGirt goes permanently free, it’s that he gets the trial in federal court he’s entitled to by statute.

And that’s not even the worst part of the paragraph!

Compare this with Gorsuch’s clear, precise lede:

On the far end of the Trail of Tears was a promise. Forced to leave their ancestral lands in Georgia and Alabama, the Creek Nation received assurances that their new lands in the West would be secure forever. In exchange for ceding “all their land, East of the Mississippi river,” the U. S. government agreed by treaty that “[t]he Creek country west of the Mississippi shall be solemnly guarantied to the Creek Indians.” Both parties settled on boundary lines for a new and “permanent home to the whole Creek nation,” located in what is now Oklahoma. The government further promised that “[no] State or Territory [shall] ever have a right to pass laws for the government of such Indians, but they shall be allowed to govern themselves.”

Today we are asked whether the land these treaties promised remains an Indian reservation for purposes of federal criminal law. Because Congress has not said otherwise, we hold the government to its word.

In a sense, this isn’t exactly a “statutory interpretation” case. There’s no actual ambiguity in the material language of the relevant treaties and statutes. The argument of the dissent, quite simply, is Andrew Jackson’s argument: that once a state’s white majority has done enough to nullify black-letter federal legal obligations to indigenous populations the law has been effectively repealed. Gorsuch absolutely shreds this disgraceful, white supremacist argument:

In the end, only one message rings true. Even the carefully selected history Oklahoma and the dissent recite is not nearly as tidy as they suggest. It supplies us with little help in discerning the law’s meaning and much potential for mischief. If anything, the persistent if unspoken message here seems to be that we should be taken by the “practical advantages” of ignoring the written law. How much easier it would be, after all, to let the State proceed as it has always assumed it might. But just imagine what it would mean to indulge that path. A State exercises jurisdiction over Native Americans with such persistence that the practice seems normal. Indian landowners lose their titles by fraud or otherwise in sufficient volume that no one remembers whose land it once was. All this continues for long enough that a reservation that was once beyond doubt becomes questionable, and then even farfetched. Sprinkle in a few predictions here, some contestable commentary there, and the job is done, a reservation is disestablished. None of these moves would be permitted in any other area of statutory interpretation, and there is no reason why they should be permitted here. That would be the rule of the strong, not the rule of law.

[…]

In the end, Oklahoma abandons any pretense of law and speaks openly about the potentially “transform[ative]” effects of a loss today. Brief for Respondent 43. Here, at least, the State is finally rejoined by the dissent. If we dared to recognize that the Creek Reservation was never disestablished, Oklahoma and dissent warn, our holding might be used by other tribes to vindicate similar treaty promises. Ultimately, Oklahoma fears that perhaps as much as half its land and roughly 1.8 million of its residents could wind up within Indian country.

It’s hard to know what to make of this self-defeating argument. Each tribe’s treaties must be considered on their own terms, and the only question before us concerns the Creek…Oklahoma replies that its situation is different because the affected population here is large and many of its residents will be surprised to find out they have been living in Indian country this whole time. But we imagine some members of the 1832 Creek Tribe would be just as surprised to find them there.

[…]

The federal government promised the Creek a reservation in perpetuity. Over time, Congress has diminished that reservation. It has sometimes restricted and other times expanded the Tribe’s authority. But Congress has never withdrawn the promised reservation. As a result, many of the arguments before us today follow a sadly familiar pattern. Yes, promises were made, but the price of keeping them has become too great, so now we should just cast a blind eye. We reject that thinking. If Congress wishes to withdraw its promises, it must say so. Unlawful acts, performed long enough and with sufficient vigor, are never enough to amend the law. To hold otherwise would be to elevate the most brazen and longstanding injustices over the law, both rewarding wrong and failing those in the right.

Roberts gets repeatedly checkmated here like Jackie Aprile Jr. playing an afternoon of chess against Garry Kasparov. (I think Roberts’s dissent nearly drowned in three inches of water.)

This isn’t an anomaly for Gorsuch either; for whatever reason this normally orthodox reactionary is along with Sonia Sotomayor the most pro-native rights justice to ever sit on the Supreme Court. Credit where credit is due.