Evangelicals and patriarchy

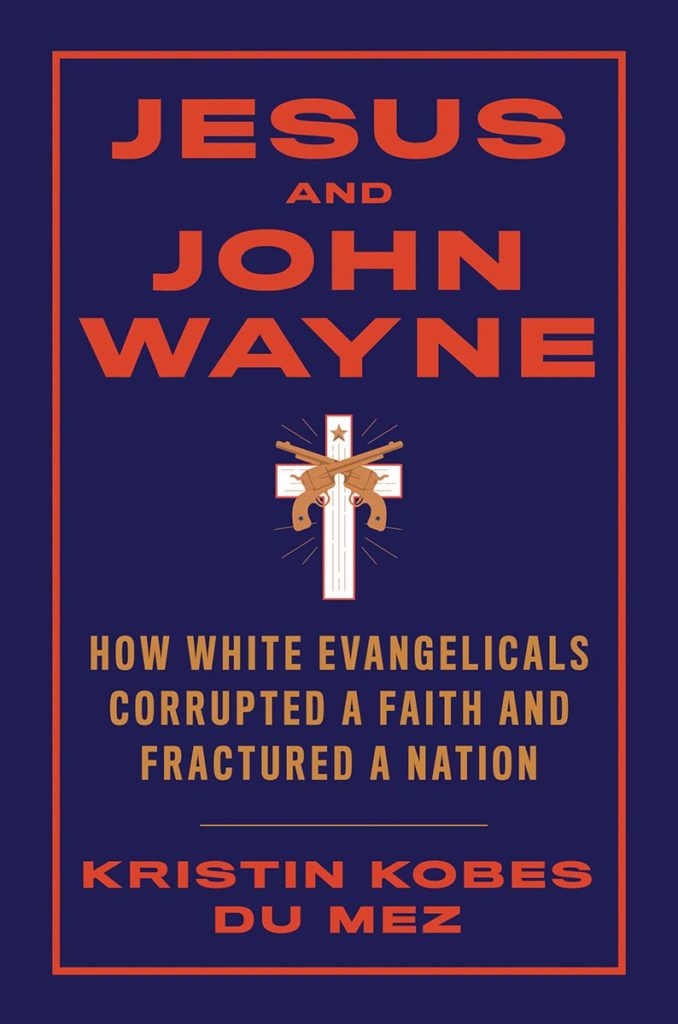

Kristen Kobes Du Mez has written what looks like a really interesting book on how the fact that Trump’s base is dominated by white evangelicals is neither surprising nor wracked with internal contradiction:

What I look to as a historian is this critical period in the post-World War II era when these gender ideals fuse with anti-communist ideology and this overarching desire to defend Christian America. The idea that takes root during this period is that Christian masculinity, Christian men, are the only thing that can protect America from godless communism.

At the same time, you have the civil rights movement destabilizing white evangelicalism and conceptions of white masculinity. Then you have feminism destabilizing traditional masculinity. And all of this comes together for evangelicals, who see their place in the culture slipping away, and they see their political power starting to erode because of this cultural displacement. That’s the moment when you see Christian nationalism linking together with a very militant conception of Christian manhood, because it’s up to the Christian man to defend his family against all sorts of domestic dangers in the culture wars, and also to defend Christian America against communists and against military threats. . .

If you understand what family values evangelicalism has always entailed — and at the very heart of it is white patriarchy, and often a militant white patriarchy — then suddenly, all sorts of evangelical political positions and cultural positions fall into place.

So evangelicals are not acting against their deeply held values when they elect Trump; they’re affirming them. Their actual views on immigration policy, on torture, on gun control, on Black Lives Matter and police brutality — they all line up pretty closely with Trump’s. These are their values, and Trump represents them. . .

In the ’40s and ’50s, it’s all about anti-communism. But once the civil rights revolution takes hold, it becomes about defending the stability of the traditional social order against all the cultural revolutions of the ’60s. But the really interesting moment for me is in the early ’90s when the Cold War comes to an end. You would think there would be a kind of resetting after the great enemy had been vanquished, but that’s not what happened.

Instead, we get the modern culture wars over sex and gender identity and all the rest. And then 9/11 happens and Islam becomes the new major threat. So it’s always shifting, and at a certain point I started asking the question, particularly post-9/11, what comes first here? Is it the fear of modern change, of whatever’s happening in the moment? Or were evangelical leaders actively seeking out those threats and stoking fear in order to maintain their militancy, to maintain their power?

Kobes Du Mez emphasizes that understanding white evangelical politics requires understanding white evangelical popular culture, which is quite self-consciously a kind of counter-culture (I’m thinking specifically here of how Mel Gibson’s The Passion of the Christ was considered a sort of grassroots [sic] response to Scorsese’s The Last Temptation of Christ, which itself was one of the earliest cause celebres of the culture wars, just at the moment when the concept of “political correctness” was congealing):

The success of John Eldredge’s book Wild at Heart [a huge bestseller that urged young Christian men to reclaim their masculinity]was a big deal in the evangelical world, and it sold millions of copies just in the US. Every college Christian men’s group was reading this. It was everywhere in the early 2000s.

There were lots of conferences celebrating this version of a rugged Christianity. It was big business, and there were lots of weekend retreats where men could go out into the wilderness and practice their masculinity. Local churches invented their own versions of this. One church I know in Washington had their own local Braveheart games that involves wrestling with pigs or something. It was all weird and different, but the point was to prove and express your masculinity. . .

[Trump] is their great protector. He’s their strongman that God has given them to protect them. So, again, the ends justify the means here. But I think it’s important to understand that the appeal of Trump to evangelicals isn’t surprising at all, because their own faith tradition has long embraced this idea of a ruthless masculine protector.

This is just the way that God works and the way that God has designed men. He filled them with testosterone so that they can fight. So there’s just much less of a conflict there. The most common thing that I hear from white evangelicals defending Trump is that they just wish he would tweet less. I don’t find a lot of concern about his actual policies or what’s in his heart.

There’s a lot to think about here, but the most basic underlying point is that what Trump is perceived to be protecting is, above all, white Christian patriarchy. The key to understanding the culture wars, and the battles over political correctness (now being referred to derisively as “wokeness” and “cancel culture”) is that they are battles over patriarchy as an ideology.

A lot of progressives — and in particular progressive men — fail to grasp the ideological commitment that drives Trump’s core support. It isn’t just random hatred and stupidity (although there’s plenty of that): it’s a commitment to a world view that could not be more fundamentally opposed to the liberal-left version of modernity. These people believe in hierarchy above all, and the single most important piece of that hierarchy is that men should exercise “headship” — in the family and society at large.

This was a critical factor in Hillary Clinton’s defeat. While it’s true that 25 years of right wing noise machine demonization of the Clintons played an important role, an even more important factor was that Clinton is a woman — and voting for Trump was, for white evangelicals in particular, the first blast of the trumpet against a monstrous regiment that is a perversion of the natural — meaning the Godly — order of things.