Erik Visits an American Grave, Part 655

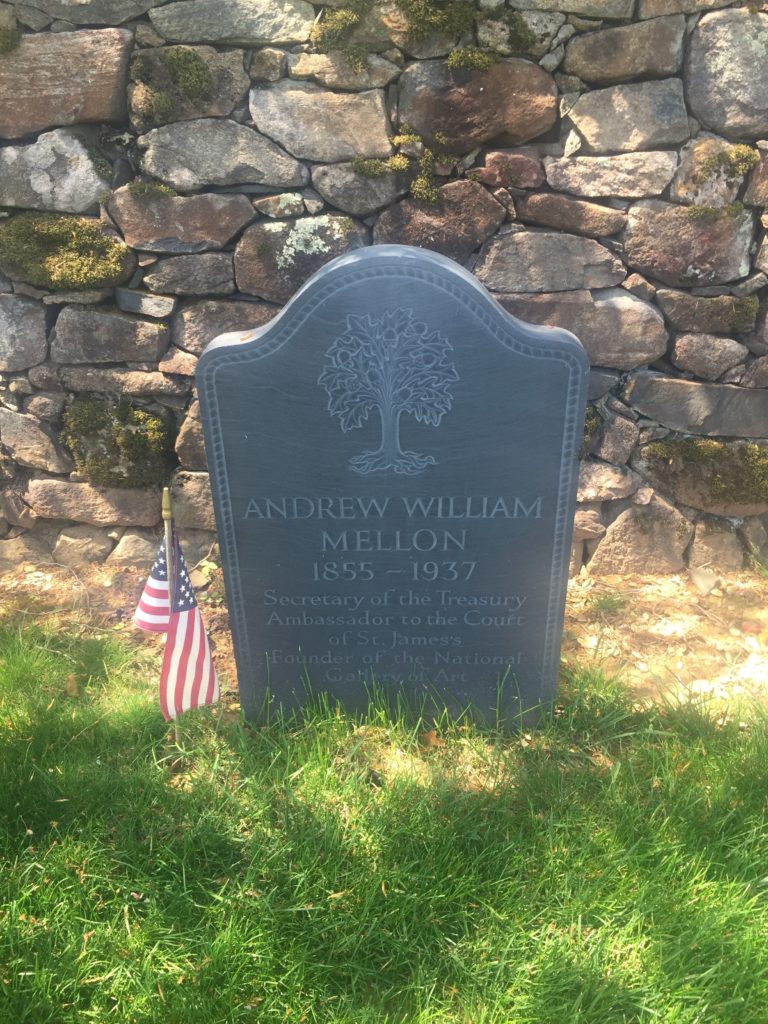

This is the grave of Andrew Mellon.

Born in 1855 in Pittsburgh, this foundational capitalist of the Gilded Age grew up among the city’s elite. His father was a banker and Andrew followed him into the business. He briefly attended what became the University of Pittsburgh but dropped out. By 1873, he was a full-time employee of his father’s company and played an increasingly leading role in it as recovered from the Panic of 1873. Even though he was still a teenager, Mellon was rapidly becoming one of the nation’s most important bankers. By 1876, he was running day-to-day operations and had power of attorney. He also became close to another leading Pittsburgh capitalist, the notorious steel baron Henry Clay Frick. The two would work together for years to make sure money flowed upwards and people remained poor. Mellon became a member of Frick’s elite hunting club in central Pennsylvania that caused the Johnstown Flood in 1889 through not maintaining an earthen dam that gave out in a storm, killing over 2,200 people. Mellon gave $1,000 to a relief fund and said nothing about it publicly.

Mellon was rich by this time but not rich enough for his ambitions. He wanted to be John D. Rockefeller. He began to expand his banking interests into industries such as coal, steel, and glass. He worked with Andrew Carnegie and Frick on much of this. Frick and he for instance got involved in shipbuilding to capitalize on the Spanish-American War and the new American involvement overseas. By 1900, he was still a good step below the equal of J.P. Morgan in terms of wealth and power, but nonetheless was one of the most well-connected and wealthiest bankers in America. He was director of everything from American Locomotive to the Pennsylvania Railroad, became a major investor in Westinghouse, and has his paws almost everywhere in the American economy. He and Frick also ran Old Overholt Distillery, though they took their names off the title when more states engaged in prohibition, in 1907. More on that in a minute.

Mellon hated Progressives. For him, people such as Theodore Roosevelt, Florence Kelley, Jane Addams, and even William Howard Taft were interfering in the glorious free market economy of the Gilded Age. All reforms were unacceptable. He was always interested in politics, primarily tariffs to support his own personal interests. That Roosevelt and Taft would bust trusts was outrageous to Mellon. By 1920, he was ready to get personally involved in turning the Republican Party away from its Progressive apostasy and back toward pre-1901 revanchist financial and social conservatism. Like, well, nearly everyone, Mellon was not a particular supporter of Warren Harding at first, but Mellon, like, well, nearly everyone, also knew they could control the nonentity they had nominated. With conservative financial forces back in charge of the party, Mellon enthusiastically fought for Harding. And when he won, Mellon got the position of Secretary of the Treasury.

Now Mellon could really implement the America he wanted. He was a bit reluctant at first. After all, he would now be moving from behind the scenes to the spotlight and he’d never been there before. There was also the Old Overholt issue. Prohibition threatened his investment, which had increased when Frick deeded Mellon his part of the company on his death. But he legally separated himself even further from the distillery while also having the Treasury Department grant him one of the medicinal exceptions to the Volstead Act. This is how Mellon operated–a hypocrite who would shape the law to benefit his personal interests. This whole incident was used as a good plot point in a few episodes of Boardwalk Empire, which did a great job using the Harding administration as a springboard for its own discussion of corrupt urban politics in the Prohibition years. Like Donald Trump nearly a century later, Mellon refused to separate his personal interests from his government service and personally lobbied members of Congress on behalf of his financial interests, even if he technically transferred control over his empire to his brother.

Mellon actually hated Prohibition. He liked a drink and he thought the Volstead Act was unenforceable. When Treasury was forced to deal with it, Mellon groaned and only half-heartedly supported any of it, which probably materially contributed to its failure. What Mellon did care about was lowering taxes on rich people and balancing the budget after the nation going into debt to fight World War I. He didn’t attempt to destroy the still recent federal income tax because he wanted to pay off those debts but the idea that the tax was redistributive was anathema to Mellon. He fought to get rid of the high-earning surtax that applied to the very rich and instead create a slightly progressive tax that lowered the obligations of people like himself and spread it down the socio-economic scale somewhat. This became core to the Revenue Act of 1918 that lowered the top marginal tax rate from 73% to 58%. This was too much of a half-measure for Mellon, who was angry about it. He was also angry about the Bonus Bill because a pension for soldiers threatened his debt fanaticism. Mellon convinced Harding to veto it, but Congress overrode that.

Mellon stayed on when Calvin Coolidge became president after Harding’s death. They were dour, tightwad peas in a pod. Mellon was easily Coolidge’s top advisor and many said he was the most influential Secretary of the Treasury since Alexander Hamilton. Mellon continued to fight for lowering top marginal tax rates and in 1924 was able to get it down to 48%, which still made him angry because he wanted 33%. But Democrats and the Progressive wing of the Republicans could combine and control Congress on these issues. So Mellon only got part of what he wanted. He had planned to resign after the 1924 election. But by then he was so obsessed with his top marginal tax rates that he stayed on for Coolidge’s full term. And in the Revenue Act of 1926, he got those top rates reduced all the way to 25%. Working closely with his deputy Ogden Mills, Mellon now went after corporate taxes and the estate tax, winning some victories on the former in the Revenue Act of 1928, but not the latter. He both took and claimed credit for the Roaring Twenties.

And so he stayed on under Herbert Hoover. Now, Mellon and Hoover initially did not have a good relationship. For as terrible a president as Hoover was, he also had his roots as a Progressive and the rich class did not trust him. Mellon tried to sabotage Hoover’s nomination in 1928, but there wasn’t anyone else. Mellon tried to convince Coolidge to go for another term, but he refused. So did 1916 candidate Charles Evans Hughes. So Mellon was stuck with Hoover. But like Hoover, Mellon believed what became the Great Depression was a short-term problem that the country would recover from by the end of 1930. He didn’t want to bail out those who had lost their money in the stock market. But the economy spiraled out of control. Mellon was absolutely horrible in the Depression. He opposed anything that would really help the American people. Hoover was mostly on board with this as well. As banks failed, their only answer was voluntary measures, featuring their antipathy to government action and regulation that simply had no functioning place any longer in a globalized twentieth century economy. The utter repudiation of the Republicans in the 1930 midterms did not lead to any policy changes. Mellon just dug deeper. He openly urged Hoover to let everyone fail, the only thing that would work in resetting the economy and that any government intervention would violate the inviolable rules of free market capitalism. However, Mellon’s fear of debt outweighed his hatred of taxes and he urged the return to the tax rates of 1924, which mostly happened in 1932.

But by 1932, Mellon was Public Enemy #2 for Democrats, just behind Hoover. Congressional Democrats led by Texas Democrat Wright Patman started impeachment proceedings against Mellon based on his massive violations of the law through his conflicts of interest through his eleven years at Treasury. Hoover couldn’t defend him anymore. Mellon resigned, Mills took over, and Hoover sent Mellon to London as ambassador to the U.K. That was a short-lived assignment, as FDR decimated Hoover that fall. Up until the end, Mellon truly believed that Hoover would win reelection. He was that deluded.

Upon his return to the U.S., Mellon mostly engaged in blasting the New Deal for violating all of his principles about the economy. He was especially furious about the 1933 Banking Act that required separation between commercial and investment banking, which had made Mellon much of his fortune while also destabilizing the economy. Things such as Social Security or unemployment insurance were fainting couch inducing for the old crab. A 1933 biography of Mellon was a best-seller because it eviscerated his corruption and responsibility for the Depression. The political machine he had built in Pittsburgh collapsed and New Dealers began winning local and congressional elections from there. Democrats also began investigating tax violations of several wealthy Americans, including Mellon. He cooperated, more or less and wasn’t charged. But right about the time this ended, in late 1936, he was diagnosed with cancer. He died in 1937.

Yeah, sure Mellon engaged in a bunch of philanthropy and the Mellon Foundation is a big grant-giver today. And yeah, he’s responsible for the establishment of the National Gallery of Art, opened in 1941 with many of the paintings Mellon spent his fortune on. Sure, this is all fine. Also, it doesn’t make up for the great evil Mellon caused. After all, the measure of a rich person is how they made their money, not what they did after they were rich and secure.

Andrew Mellon is buried in Trinity Episcopal Church Cemetery, Upperville, Virginia, which is near where he retired after he was such a pariah in Pittsburgh that he couldn’t go home in 1933.

If you would like this series to visit other capitalist pigs, you can donate to cover the required expenses here. Steve Jobs is in Palo Alto, California and Sam Walton is in Bentonville, Arkansas. Previous posts in this series are archived here.