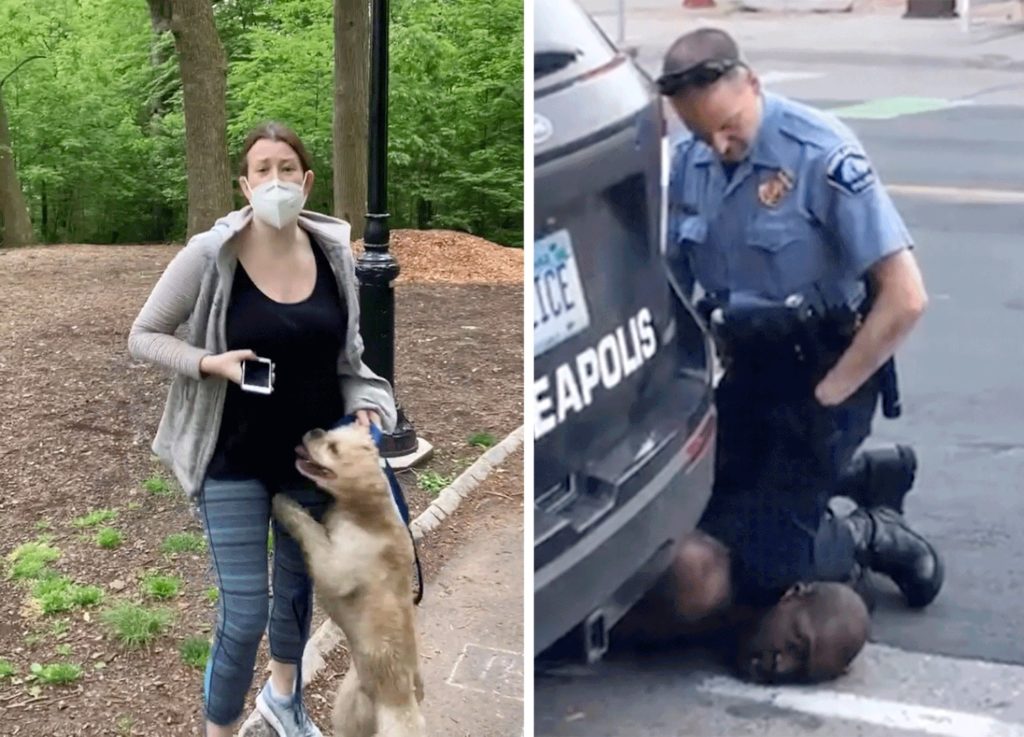

White Women and White Supremacy

The political scientist Jenn Jackson has an excellent piece in Teen Vogue on the centrality of white women to the maintenance of white supremacy, as true in 2020 as in 1860 or 1935.

But women and white supremacy were bosom buddies long before we had the technology to capture them on film.

During the period of legal enslavement of continental Africans and their African-American descendants in the United States, the slave household was the primary domain of white women who were married to white slave masters. They were called “slave mistresses.” Slave mistresses set out to “civilize” enslaved black women whom they forced to nurse their children, cook the family’s food, and act as handmaids for the white children who technically owned them. According to Duke University historian Thavolia Glymph’s book Out of the House of Bondage, “mistresses beat and humiliated slaves” in an effort to silence discontent and quell resistance. Meanwhile, these enslaved women’s proximity to slave masters made them even more susceptible to rape and other physical abuse. These aren’t the popular images and myths about slavery, though.

What is critical here is that white women were working in the plantation household to normalize white supremacy. Thus, even when the peculiar institution of slavery was eradicated, the culture and logic underlying it prevailed.

The Ku Klux Klan was founded in December 1865 — just days after the States ratified the 13th amendment abolishing slavery and during the period of Reconstruction, which lasted from 1865 to 1877 and during which some Southern political leaders made an attempt to “build an interracial democracy on the ashes of slavery,” as Columbia University history professor Eric Foner wrote in The New York Times. Black Americans during this period saw increased access to voting and political representation, property rights, and education. Southern whites, many of whom were destitute and economically unstable after the vast material and human losses of the Civil War, felt threatened by the newfound freedom and success of previously enslaved black Americans. In response to the potential loss of their “heritage,” new organizations emerged at the end of the 19th century.

One of the most prominent groups to participate in the preservation and purification of the failed white supremacist regime was the United Daughters of the Confederacy, founded in 1894. The Daughters worked alongside organizations like the Klan to grow white supremacist frameworks in the South. They were integral in erecting statues and monuments to commemorate the Confederate generals and soldiers who were their own family members. While they claim these efforts were about history, they instead sanitized our memory of those states that had seceded from the Union, and downplayed the Confederate states’ enduring commitments to those ideologies even after the war ended.

During that time, the perception that black Americans would dispossess white Southerners was met with swift racial violence in the form of lynchings.

There are many accounts of the horrors of the more than 4,000 recorded lynchings in the United States. These events between 1877 and 1950 are often described using the term “strange fruit” (popularized especially by the Billie Holiday song) because beaten and burned black Americans’ bodies would be swinging from trees. The earliest and arguably most thorough account of white women’s role in the lynchings of black American men came from anti-lynching activist and journalist Ida B. Wells in A Red Record.

Wells found that black men accused of raping white women were often lynched without ever going to trial which “had the effect of fastening the odium” upon them. The clearest example of this “odium” is the brutal 1955 kidnapping and killing of 14-year-old Emmett Till for supposedly whistling at Carolyn Bryant Donham — a fact that she now admits was a lie. Perhaps these events shed light on the strange invisibility of white women among the white nationalists rallying in Charlottesville and some of their political behavior today.

Not to mention the Scottsboro Boys.

In conclusion, Amy Cooper is just the latest in a long line of racist white women at the forefront of racial oppression. And we have to recognize the special role of women in this, especially at a time when white men are, rightfully, being seen as the the real problem in America due to their overwhelming support of Trump. The problem of racism is much deeper than Donald Trump and his supporters. It’s in the heart and soul of every white person unless they fight it actively and even then it is still there. White women have played a significant role in creating and supporting this racist society, past and present, and it must be recognized as such.