What the Confederacy Was

Always worth a reminder:

Nascent Confederates were candid about their motives; indeed, they trumpeted them to the world. Most states wrote justifications of their decision to rebel, as Jefferson had in the Declaration of Independence. Mississippi’s, called the “Declaration of Immediate Causes,” said bluntly that the state’s “position is thoroughly identified with the institution of slavery.” The North, it said, was advocating “negro equality, socially and politically,” leaving Mississippi no choice but to “submit to degradation, and to the loss of property worth four billions of money or … secede from the Union.”

In late February 1861, in Montgomery, Alabama, the seven breakaway states formed the C.S.A.; swore in a president, Jefferson Davis; and wrote a constitution. That constitution aimed to perfect the original by dispensing with all the issues about slavery and representation that had plagued political life in the former U.S. The document recognized the constituent states as sovereign entities (though it did not confer on them the right to secede, confirming Lincoln’s point that no government ever provides for its own dissolution). It put the country under God and mandated a one-term presidency, of six years. It purged the original of euphemisms, using the term slaves instead of other persons in its three-fifths and fugitive-slave clauses. It bound the Congress and territorial governments to recognize and protect “the institution of negro slavery.” But the centerpiece of the Confederate constitution—the words that upend any attempt to cast it simply as a copy of the original—was a wholly new clause that prohibited the government from ever changing the law of slavery: “No … law denying or impairing the right of property in negro slaves shall be passed.” It also moved to limit democracy by explicitly confining the right to vote to white men. Confederates wrote themselves a pro-slavery constitution for a pro-slavery state.

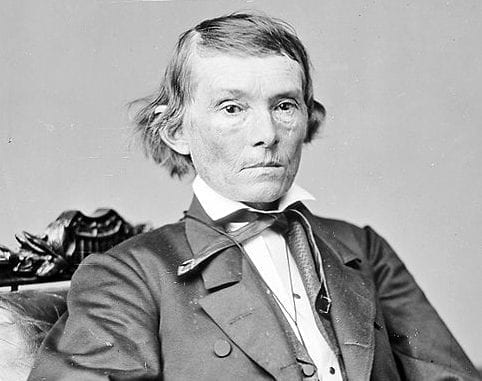

Shortly after this constitution was written, Alexander Stephens, the vice president of the C.S.A., offered a political manifesto for the slaveholders’ new republic. Training his sights on the eight upper-South states that were still refusing to secede, he offered a blunt assessment of the difference between the old Union and the new. The original American Union “rested upon the assumption of the equality of the races,” he explained. But “our new government is founded upon exactly the opposite ideas: its foundations are laid, its cornerstone rests, upon the great truth that the negro is not equal to the white man; that slavery is his natural … condition. This, our new government, is the first, in the history of the world, based on this great … truth.” A statue of Alexander Stephens now stands in the U.S. Capitol; it is one of a group that includes Jefferson Davis and Robert E. Lee, targeted for removal.

There’s no more reason to have statues commemorating confederate leaders than statutes commemorating Nazi ones. It’s really not a remotely difficult question. It wasn’t a liberal state that failed to live up to its stated ideals in myriad ways, it was a state whose core values and indeed sole raison d’etre were chattel slavery and white supremacy. Tear them down.