This Day in Labor History: May 29, 1935

On May 29, 1935, a strike by mineworkers in Northern Rhodesia (today Zambia) to protest taxes levied on them by British colonial administrators was met with murderous violence, with about 28 workers killed or injured. This was an early labor protest that failed, but also helped build the nationalist and anti-colonial movements that sprung up in Africa and which successfully challenged European imperialism after World War II.

Colonialism allowed nations such as Britain, France, Belgium, and the United State to loot the global south, stealing resources to enrich themselves. When the British aggressively took over large swaths of Africa in the late nineteenth century, this was very much on their mind. One of those areas became known as Northern Rhodesia. Copper was discovered there and these mines, which also had American investment, were major sources of income for the colonial state.

Now, the British were notorious for forcing colonial subjects to suffer, even to the point of death, to get the product out. This directly contributed to the Irish potato famine and the great nineteenth century famines in India. In both cases, the British were utterly indifferent to starvation and instead prioritized their god, the free market.

The development of the mines in modern Zambia led people from around central Africa to migrate there for economic opportunity. It also led a lot of white settlers and colonialists moving there to rule over these Africans. With the good economic possibilities of mining, many whites wanted to take those jobs as well and they demanded higher wages than African miners. The government created a system of debt bondage to control these black laborers and discourage them from moving to the mines. In 1901, the British South African Company implemented a hut tax on African migrants to northeastern Northern Rhodesia that could cost them up to six months wages for the right to live there. By 1913, this tax had been expanded to much of the colony. The idea was to place the Africans in a state of debt bondage that allowed whites to control their labor.

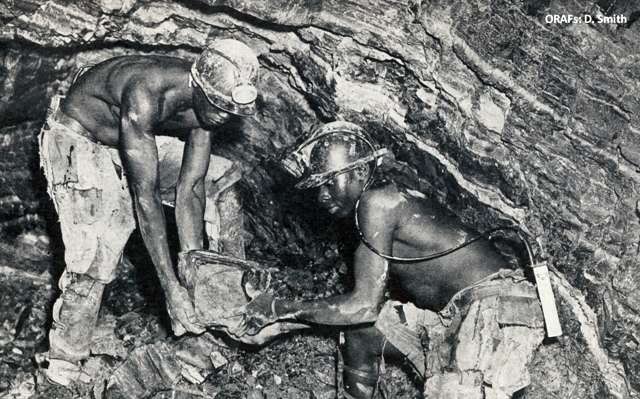

Africans were always very angry at these taxes and there were various revolts of one kind or another, but the colonial police force could be brutal in suppressing any organized dissent. It could then force indebted Africans into the mines whether they wanted to go there or not. In the booming economy of the 1920s, this kept the labor force supply plentiful. They were treated horribly, with harassment and violence common parts of life. They were banned from higher-paid jobs and they were paid massively less than white miners. The miners died of silicosis in a working atmosphere that was utterly indifferent to safety. Bosses engaged in physical abuse of black workers on a routine basis.

And then the Great Depression hit. Suddenly, the mine owners didn’t need all these African miners. Copper prices collapsed. But where were the miners to go? By this time, many of them knew little else and it’s not as if there were other reasonable economic opportunities for them. Mines started shutting down in 1931 and several large ones closed in the following year. In 1930, the mines employed nearly 32,000 people and by the end of 1932, fewer than 7,000. Europeans left the area and Africans remained. The colonial state still wanted that money. Remember the British earlier with the starvation of others. Well, things hadn’t changed that much by 1935. And so to increase revenues, it up to doubled the taxes on urban African residents, which included the miners, while lowering them a bit for rural people.

On May 21, a tax increase was announced for the workers at Mulifulira mine, from 12 to 15 shillings a year. The workers immediately walked off the job in outrage. This was the beginning of the Copperbelt Strike. It was unplanned and didn’t have any leaders. There weren’t unions involved to speak of, though in the weeks ahead of this, there had some been talk of strike in the mines. This was a furious response by angry workers facing multiple layers of discrimination in their lives. The three Africans who started it were named William Sankata, Ngostino Mwamba and James Mutali. They were Bemba, which made up the largest percentage of the miners. Dancers in the Mbeni tradition, which was a sort of jester dance form to make fun of the colonial administration, were used to communicate between the different mines. The Mbeni were similar to other mutual aid groups among the miners that formed to make life relatively decent. Over the next couple of days, the strike spread to other mines. Dozens of workers were arrested and the colonialists sent troops from Lusaka to guard the mines.

On May 29, at Roan Antelope, tribal leaders led a broader protest against the mines. Protestors began throwing rocks. The police opened fire. It was a massacre, with six dead and at least seventeen wounded. This shocking and unexpected violence led to the workers deciding it was not worth it. The strike ended the next day, after 44 workers were arrested. By May 31, most of the miners were back at work.

In the aftermath, the colonial officials learned nothing. To them, while they admitted that the tax raise was the immediate cause of the strike, the solution was detribalization so the workers could be controlled by Europeans. Moreover, they still believed the tax increase was completely justified, though they admitted that maybe the corporal punishment of workers was a problem. Rather than question themselves, they just blamed backwards African tribes. The new governor of Northern Rhodesia did create a sort of tribal council to talk things over with, but the closest American comparison here might be company unionism–basically a voice without power. Missionaries came to the region in full force after this, under the impression that Christianity and civilization would create a docile work force and break people from their tribal identity. The government did provide more health care to the miners as well. The mines also started reopening later in 1935 and slowly returned to normal after that.

In the aftermath, nationalism grew. This was a key moment for the people of what became Zambia to rediscover their tribal roots, form nascent labor unions, critique colonialism more holistically, and organize for their rights. A second wave of strikes took place in 1940 in a more organized fashion, though seventeen workers were killed. Zambia finally became independent of British colonialism in 1964.

If you want to read more about this strike, one article is Ian Henderson, “Early African Leadership: The Copperbelt Disturbances of 1935 and 1940,” published in the October 1975 edition of Journal of Southern African Studies.

This is the 357th post in this series. Previous posts are archived here.