Mitigation and chaos

Matt Yglesias lays out nicely in Vox how a mitigation strategy that keeps the pandemic from overwhelming the health care system will save some lives, but still result in probably upwards of one million excess deaths in the US from the direct and indirect results of the disease. Lowering that number requires aggressive, well-organized action to suppress the total number of infections, not merely mitigate their effects as the population moves toward herd immunity:

With the disease seemingly beaten back domestically, Hong Kong is now in a position to start switching emphasis to a strategy focused on border controls. With the pandemic still raging globally, the city can’t let its guard down entirely. And because Hong Kong is so small and dependent on international commerce, just opening up the domestic service economy can’t really save the city from serious economic problems.

But the city has a clearly articulated strategy that it calls “suppress and lift”: ease restrictions now when cases are at zero, but then clamp back down as necessary to push cases back down if they pop up.

Taiwan has also had no new cases for several days, and since April 6, all of Taiwan’s reported cases have stemmed from a single naval vessel’s goodwill mission to the island of Palau rather than community spread. New Zealand has not done quite this well, but the government believes it has successfully identified and isolated all of the country’s coronavirus cases and is lifting restrictions, on the claim that the virus has been “eliminated” in the country.

South Korea’s outbreak is now down to single-digit numbers of new cases per week, and a key test for the country is whether an anticipated surge of holiday travel this week to the island of Jeju (a major Korean tourist destination) will lead to a new wave, or if the peninsula can suppress spread of the disease. South Korean professional baseball also resumed this week, though without fans in the stands.

The United States, meanwhile, is moving to open up on the basis of a vaguely articulated assumption that settling for mitigation is good enough.

One reason for the pressure to open up is that while widespread orders to shelter in place have clearly succeeded in slowing the spread of infection, they’re not bringing case volumes down quickly. Authorities fear the economic pain of prolonged shutdowns, and it seems like the mass public is growing impatient and starting to bend the rules.

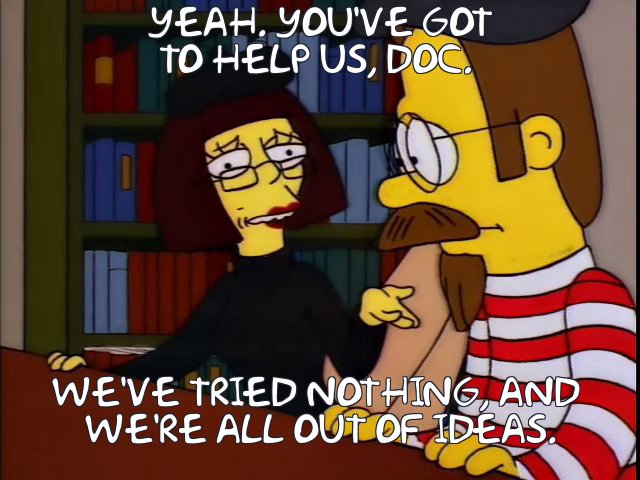

But the reality is that the United States has not really triedthe strategies that have made suppression successful. To accomplish that, America would need to invest in expanding the volume of tests, invest in more contact tracers, and create centralized quarantine facilities so that infected people aren’t simply sent home to infect the rest of their household.

Since the US didn’t spend April doing that, trying to achieve suppression — along the lines of Taiwan, Hong Kong, Korea, and New Zealand — would necessarily involve more delay and more economic pain. But doing so would save potentially tens or hundreds of thousands of lives and almost certainly lead to a better economic outcome by allowing activity to truly restart.

What seems likely to happen now is that, as states relax restrictions and people get tired of staying home, cases will start to rise from their current plateau. Then restrictions will be tightened again, while a national suppression strategy — and such a strategy pretty much needs to be national, since the virus rejects federalism as a concept — remains non-existent, because the federal government is run by malevolent nitwits.

After we go through this cycle a couple of times over the course of the next few months, patience will run out completely and we’ll descend into genuine political and epidemiological chaos sometime this fall, probably before November 3rd.

This public service message has been brought to you be a fourth responder.*

*Fourth responders are everyone in the opining classes. First responders are front line emergency workers, second responders treat the victims of the crisis after they are removed from the front lines, and third responders take substantive political action to try to ameliorate the crisis. Fourth responders critique everyone who is doing actual work.

. . . Commenter epidemiologist provides a treatment if not a vaccine for bloggy snark:

Disease response can be conceptualized as primary, secondary, or tertiary prevention. Primary prevention is actually preventing you from getting sick via any means such as vaccination, education, or policy. Secondary prevention is intended to reduce the impact of disease that has already occurred, preventing additional morbidity and mortality. Both screening and acute treatment of illness are secondary prevention. Tertiary prevention attempts to alleviate and reduce the impact of ongoing health problems, e.g. through rehabilitation.

I prefer this framework because, rather than emphasizing individual heroism and proximity to danger, it emphasizes what is actually done for our “patients” in public health: the entire population at risk of disease. Many primary prevention activities are quite low risk to the worker, including making policy. Yet preventing a person from ever developing a particular disease is a priceless humanitarian activity that protects first responders and the general population alike.

Obviously, we should be grateful to people who are risking their health and lives to provide direct service to others. But I think our emphasis on heroic individual service in the US is not helping us here. If you’re not sick right now, aren’t you grateful? Do you scorn the contribution of someone staying home, struggling to homeschool their kid, just because they are relatively safe? Of course not! People staying home, people making deliveries, people doing any sort of essential job at all, are engaged in a very important, solidaristic project of primary prevention even while under threat from our government, our employers, our fellow citizens, and nature itself. No one here has anything to apologize for.