COVID-19 and the American Working Class

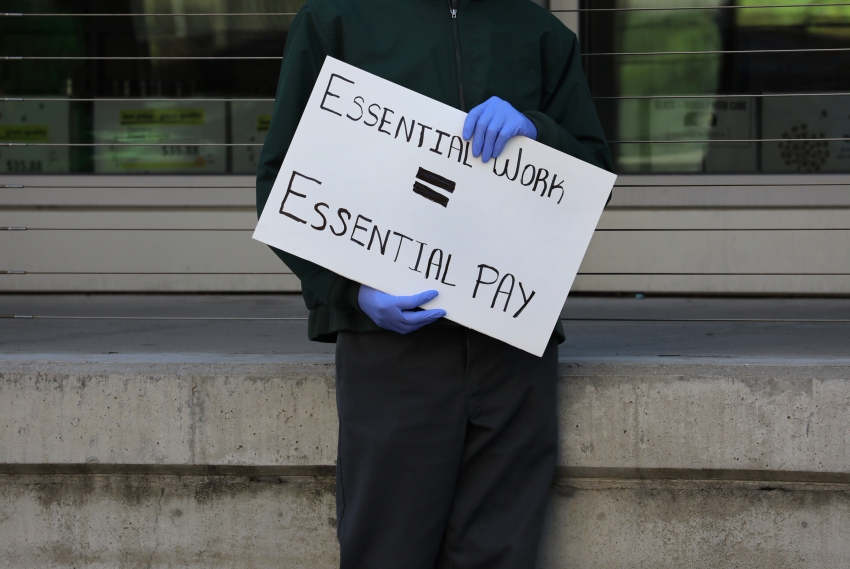

Natural disasters are in fact events that show to all the inequalities in society. COVID-19 is an extreme case of this because it is a global event. Here in the United States, a nation that has spent decades making the lives of workers markedly worse, busting unions to their weakest point in a century, and recreating the Gilded Age has not surprisingly seen its response to the pandemic be one that endangers some workers while impoverishing many more. And yet, people also respond to these issues with resistance as well, fighting for their lives and their futures. There’s been several stories about this recently. Here are just a few of them.

First, employers, not surprisingly, are using COVID-19 as an opportunity to continue their mania for unionbusting.

Truck drivers and warehouse workers at Cort Furniture Rental in New Jersey had spent months trying to unionize in the hopes of securing higher wages and better benefits. By early this year, they thought they were on the cusp of success.

But when the coronavirus arrived, Cort, which is owned by Warren Buffett’s Berkshire Hathaway, laid off its truck drivers and replaced them with contractors, workers said. The union-organizing plans were dashed.

“They fired us because we tried to start a union,” said Julio Perez, who worked in Cort’s warehouse in North Bergen, N.J.

As American companies lay off millions of workers, some appear to be taking advantage of the coronavirus crisis to target workers who are in or hope to join unions, according to interviews with more than two dozen workers, labor activists and employment lawyers.

…

It’s hard — sometimes impossible — to prove that a company is dumping workers in order to undermine a union as opposed to simple cost-cutting.

David Martinez and Peter Mackay have no doubt. They had worked for years at Uovo Fine Art in Queens, N.Y., storing, packaging and transporting artwork among the company’s warehouses. When the coronavirus started spreading, the men knew business would slow down, but they figured they would be fine, in part because of their seniority at Uovo.

But Mr. Martinez and Mr. Mackay had been leading a push to unionize the company’s workers. When Uovo furloughed most of its staff last month, informing them that they would keep receiving paychecks, Mr. Martinez and Mr. Mackay were among the few to permanently lose their jobs.

“This is obviously retaliation,” said Mr. Mackay, who had worked at Uovo as a driver and art handler for more than five years.

Like these employers who don’t want to take bailout money if they have to use it to help their workers, employers facing union campaigns will be as short-sighted as possible in order to protect their power at the workplace.

Nowhere has this been more obvious than at the meatpacking plants. Even though several of these are unionized, the low-wage work and often immigrant or undocumented workforce makes these very dangerous places to work. In fact, the only reason we are really caring about these workers is now is that they could infect us. We paid very little attention to the conditions of meatpacking four months ago where workers were still getting hurt and sick at some of the highest rates in the nation. That’s because we didn’t have to. Now we do. And what we are finding out is that employers’ utter indifference to workers’ fates has fatal consequences. Carmen Dominguez, a union steward in a Pennsylvania plant, had an op-ed in the Times a few days ago about this:

On a normal day, work at a meatpacking plant is not easy. The slaughterhouse is boiling hot. People who aren’t used to the temperature can feel as if they are experiencing high blood pressure. The freezer is super cold and will amplify any flulike symptoms. Workers wear as many layers as they can to stay warm, but it is difficult.

In the past month, two of my co-workers died from Covid-19. The company instituted protective measures, but it was too late. The virus spread quickly through our communities. I work in a plant with 1,400 employees. A majority of us are immigrants. Companywide communications are translated into Spanish, Arabic and Haitian Creole.

Our work is essential to feeding the nation, yet plants like mine have become hot spots for the virus. On Tuesday, President Trump said that he would declare meat processing plants “critical infrastructure” to avoid a shortage in the supply chain. Already, thousands of meatpacking workers across the country have become sick at work.

Our union, the United Food & Commercial Workers, demanded at the national level that meatpacking plants restructure themselves to accommodate safety measures and provide personal protective equipment to all employees. Our plant temporarily closed on April 2, before the deaths. At that time, 19 people had tested positive. JBS remodeled the floor in line with coronavirus safety measures secretary of health for Pennsylvania, Dr. Rachel Levine, ordered. The doors reopened on April 20.

The thing here is that a decent society would be ordering meatpacking plants to improve conditions to ensure worker safety long before this. This plant shows that despite the overcrowded and uncomfortable conditions, even current plants can be re-engineered to some extent at least to ensure greater worker safety. This is the kind of thing that has to be at the top of our agenda going forward. And yet, like the pesticide scares of the 1980s that the chemical companies and agribusiness solved by creating new pesticides that did not linger on fruit but instead exposed workers to more intense doses and then the activists stopped caring about the issue once they were safe, I fear that the eventual return to normal will once again lead to us to not care about these workers who are out of sight.

And in fact, our entire New Gilded Age society is responsible for this and needs a serious reshaping. If Silicon Valley is the new Ford and GE, then maybe their workers will be like the workers of the Great Depression and organize to change their conditions and gain power over the techbro overlords who are today’s Henry Ford. Now, talk of a “general strike” at Amazon and other companies on May Day was as ridiculous as these calls always are–we are nowhere close to this and if we are, it’s not activists at these companies but everyday workers just not showing up to labor in unsafe conditions, which puts us closer to the DuBois definition of the slave general strike than it does to the leftist fantasy of the syndicalist revolution. There was no “mass strike action” on Friday, despite the left media’s constant hopes for one. This isn’t to denigrate the workers who are trying to stand up to the behemoths of the New Gilded Age. Instead, my critique is about how we talk about these sorts of events.

Rather, as Jamelle Bouie reminds us, these early actions are potentially laying the groundwork for bigger actions to come:

Workers at Whole Foods, owned by Amazon, went on strike to demand paid leave and free coronavirus testing, as did workers for the grocery-delivery service Instacart, who demanded protective supplies and hazard pay. Sanitation workers in Pittsburgh staged a similar strike over a lack of protective gear, and workers at America’s meatpacking plants are staying home rather than deal with unsafe conditions.

It’s true these actions have been limited in scope and scale. But if they continue, and if they increase, they may come to represent the first stirrings of something much larger. The consequential strike wave of 1934 — which paved the way for the National Labor Relations Act and created new political space for serious government action on behalf of labor — was presaged by a year of unrest in workplaces across the country, from factories and farms to newspaper offices and Hollywood sets.

These workers weren’t just discontented. They were also coming into their own as workers, beginning to see themselves as a class that when organized properly can work its will on the nation’s economy and political system.

American labor is at its lowest point since the New Deal era. Private-sector unionization is at a historic low, and entire segments of the economy are unorganized. Depression-era labor leaders could look to President Franklin Roosevelt as an ally — or at least someone open to negotiation and bargaining — but labor today must face off against the relentlessly anti-union Donald Trump. Organized capital, working through the Republican Party, has a powerful grip on the nation’s legal institutions, including the Supreme Court, whose conservative majority appears ready to make the entire United States an open shop.

The inequities and inequalities of capitalist society remain. American workers continue to face deprivation and exploitation, realities the coronavirus crisis has made abundantly clear.

The strikes and protests of the past month have been small, but they aren’t inconsequential. The militancy born of immediate self-protection and self-interest can grow into calls for deeper, broader transformation. And if the United States continues to stumble its way into yet another generation-defining economic catastrophe, we may find that even more of its working class comes to understand itself as an agent of change — and action.

We can certainly hope so, as this is what needs to happen. That’s not only true in the grocery stores and Amazon warehouses, but with higher education, as colleges and universities use the virus as an excuse to slash employees and there are legitimate fears that the horrors of online education will be pushed upon us as a permanent scenario, even though students despise it. Higher education is just one of many industries where the effects of this hell are just beginning to be felt. Fighting for our rights as workers is something that is required no matter our field. If you feel secure today, you may well not be tomorrow. And it is the collapse of huge parts of the economy over the long haul that leads to a second Great Depression.

But there is reason to hope. Victories are important to celebrate. And that can come from the international scene too, such as in France with Amazon.

As early as March 17, the day France’s national lockdown took effect, Amazon warehouse workers held protests and strikes. The unions that represent them railed against a lack of hand sanitizer and risks of overcrowding, and more than 200 of the company’s roughly 10,000 warehouse employees gave formal notice that they were refusing to work in unsafe conditions. Amid the outcry, national labor inspectors ordered Amazon to address safety hazards found at several of the company’s warehouses.

Then two weeks ago, in response to a separate union complaint, a judge in a Parisian suburb found Amazon still hadn’t done enough to protect workplace safety and ordered the company to limit warehouse activity to certain essential items — food, and hygiene and medical products — until it developed improved health and safety measures with labor unions. Noncompliance would come with a stiff penalty: a 1 million euro (about $1.08 million) fine per day and per violation.

At first, Amazon screamed bloody murder. The ruling was too complex to obey, the company said, before filing an appeal and announcing it would suspend activity at all of its French warehouses until further notice. The head of Amazon in France embarked on a media blitz to defend company safety practices, saying that only a small number of salaried workers were actually participating in the strikes and suggesting that overzealous unions were harming consumers.

But behind the scenes, the company took a different tack, entering detailed discussions with employee representatives about how to improve safety — and in an appeal ruling last week, a judge acknowledged that the company had made changes at several of its warehouses. But she also ruled that Amazon still hadn’t created a companywide evaluation method that could be applied to all of its sites. While she rejected the appeal, the judge also lowered the fine for noncompliance to 100,000 euros (around $108,000) per violation and expanded the range of items the company can distribute until it completes more in-depth safety talks — adding tech, home-office and pet products to the list.

Amazon maintains that the risks of breaking the order’s limits on what it can sell are too high and has not yet said when it plans to reopen warehouses, but workers continue to receive full pay and the company says that it plans to follow the judge’s decision. (Julie Valette, an Amazon spokeswoman, told me that the company is “going to comply” with the court order to consult employee representatives, with talks set to begin in the “coming days.”)

In Amazon’s version of events, nit-picking labor activists conjured up a couple of misguided court rulings — a narrative that fits nicely with Anglo-American stereotypes about doing business in France. But more than anything, the episode shines a light on the benefits of aggressively confronting Amazon: It was only through worker-led protest and a tough-handed response from courts that the tech behemoth began adjusting its behavior to better meet worker needs. As warehouse employees saw firsthand, Amazon often made improvements after it was pressured to do so.

And this is what we all have to hold on to–the need to continue pressuring politicians and employers in all parts of this hell we are living through. It’s the only answer. We may often lose. It may take a long time. After all, the Great Depression started in 1929 and it took the huge strikes of 1935 that paved the way for the National Labor Relations Act in 1935 and then continued worker activism that eventually led to the Fair Labor Standards Act in 1938. That’s a very long time. The history of organizing in the early 30s is an interesting one, but the bigger point is that it took lots of little events over a very long period of time in terms of the lifespan of a person to get the working class where it needed to go. That may be the case today too.