Cholera and Our Cities

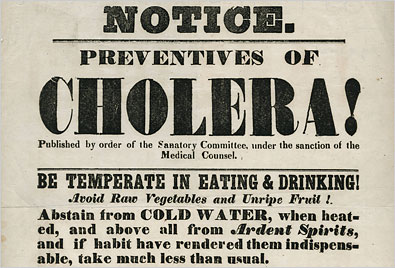

One thing about living through a pandemic is that it’s a good time to discuss other pandemics. One of the biggest public health issues in the 19th century was cholera, with three mass epidemics: 1832, 1849, and 1866, as well as plenty of smaller outbreaks. No one knew what caused this fatal illness. But they could guess. Nineteenth century went far to shape their landscapes, both urban and rural, about how they read the health of the land. Certain landscapes were seen as sickly, others as healthful. Conevery Bolton Valencius’ The Health of the Country is good on this in the rural context. One way these cholera epidemics changed both the U.S. and Europe was getting people behind the idea of parks so they could escape the miasma of the urban air.

“The fear of miasma probably made the most significant impact on the built environment in the wake of cholera and yellow fever epidemics,” says Sara Jensen Carr, an assistant professor of architecture, urbanism and landscape at Northeastern University. “Chiefly, it drove massive infrastructural initiatives in emerging cities, such as the installation of underground wastewater systems. That infrastructure in turn often meant the streets above them were made straighter and wider, as well as paved over so they could more easily be washed down at the end of the day so piles of waste would not emit miasmic gases. Marshy areas of cities were also filled in, which allowed for the expansion of industry and housing as well.”

Carr, author of the forthcoming book The Topography of Wellness: Health and the American Urban Landscape, says that while the familiar city street grid dates back to Ancient Rome, it grew in popularity because of the infrastructure improvements implemented in reaction to pandemics. Long, straight thoroughfares eliminated the pooling of fetid water in road curves and allowed for the installation of long drinking water and sewer pipes.

Another miasma theory devotee, landscape architect Frederick Law Olmsted, advocated for the healing powers of parks, which he believed could act like urban lungs as “outlets for foul air and inlets for pure air.”

“His writing often references the importance of large open spaces to allow people to access fresh air and sunlight, and discusses how air could be ‘disinfected’ by sun and foliage,” Carr says. Planning for Central Park, which would be designed by Olmsted and Calvert Vaux, began in the immediate aftermath of New York’s second cholera outbreak. Thanks to the success of that project, Olmsted, whose first child had died of cholera, went on to design more than 100 public parks and recreation grounds including those in Boston, Buffalo, Chicago and Detroit.

Of course, cholera is about contaminated water, not air. But it’s not as if Olmstead or others were wrong that parks and good air would improve people’s lives and health, even if they didn’t quite understand all the details.