This Day in Labor History: April 6, 1905

On April 6, 1905, the International Brotherhood of Teamsters began a sympathy strike in support of striking clothing cutters at Montgomery Ward in Chicago. This moment significantly raised tensions in the strike, leading to the second most fatalities of any twentieth century American strike. The failure of this strike would also lead to a severe weakening of the Chicago labor movement for the next three decades.

On December 15, 1904, clothing cutters at Montgomery Ward went on strike because the company was hiring non-union cutters, undermining their ability to make a living. The company moved quickly to destroy the union by locking all the workers out, hoping to starve them into submission. Chicago employers had been strongly anti-union for a long time. Moreover, they were highly organized. Chicago had already been the scene of Haymarket and Pullman and its employer class was determined to the keep the city as union-free as possible, with the open shop as its highest principle. In 1902, when telephone factory workers struck, the city’s capitalists formed the Employers’ Association of Chicago to organize anti-union efforts. The EA crushed that strike and then several more in the next two years.

The EA and Teamsters were soon at war. Some of this had to do with general anti-union animus and the Teamsters’ overall strength, but a lot of it was that the Teamsters had an uncommon culture of solidarity with other unions that remains strong today. It frequently engaged in sympathy strikes, including in a 1903 strike of brass molders. Because the Teamsters controlled the city’s transportation network, its support was critical for other unions to succeed. In order to maximize its power, in 1904, the Teamsters agreed that all of its contracts would expire on May 1, 1905. So the EA decided that it would not negotiate any new contracts with the union after that date. The growing hostilities between the two sides were very real and trending toward violence.

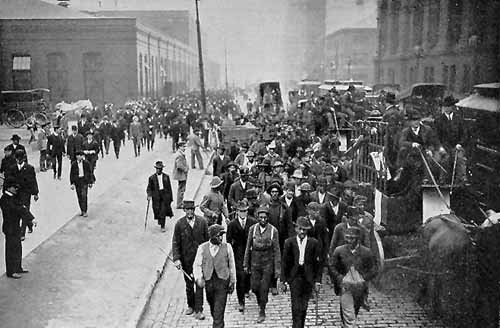

So when the Montgomery Ward workers went on strike and then were locked out, the issues were much larger than a single employer. It was about who controlled the workplace in Chicago. By the beginning of April, there were about 5,000 workers on the picket line, mostly tailors and other skilled textile workers. When the Teamsters decided to call a sympathy strike and send its 10,000 members to the picket lines, this significantly increased the stakes in the strike. The next day, the owners decided to ram through heavily guarded wagons full of materials through the lines. About 1,000 strikers attacked those wagons. Incidents like this became increasingly common. By April 23, the original garment workers strike was basically forgotten about. Somewhat upset by this, the tailors asked the unions to end their sympathy strikes. The Teamsters agreed if the employers would hire back all strikers. But the EA wanted to destroy the Teamsters and they refused after Montgomery Ward said it would be bound by whatever the EA wanted. The strike continued and, infuriated, the Teamsters called another 25,000 workers off the job on April 25. On April 29, another crowd of about 1,000 strikers and sympathizers (commonly a large part of strikes at this time) battled with police, leading to three people getting shot and two stabbed. The mayor banned firearms being carried by civilians after this. That day, a court indicted all of Chicago’s labor leaders on charges of conspiracy to restrain trade and incitement to violence. Courts issued the odious injunctions that stopped them from doing anything and threatened their existence.

On May 4, a full-fledged riot took place. About 5,000 workers and sympathizers attacked anyone they thought was moving goods. Given that most of the unions were all-white, that meant many of the strikebreakers were African-American. It was hardly surprising that some would agree to be strikebreakers. The unions were openly hostile and they needed the work. The EA was directly recruiting black teamsters from St. Louis with the promise of high wages. It added an additional racial tension to the strike, one that again showed how racism gets in the way of class solidarity, over and over again. As rocks were being thrown, some strikebreakers opened fire on strikers and one died. Other workers died in various other incidents, a total of 21 throughout the entire strike.

On May 7, the unions appealed to Theodore Roosevelt to mediate the strike. After all, he had done so three years earlier with the Pennsylvania anthracite workers. But, see, Roosevelt managed to create his own publicity around his reformist efforts while in fact being a close friend of unrestrained capital. He did meet with some union leaders, but he publicly denounced the strike and the violence committed by workers and their sympathizers, while not denouncing the actions of the EA or of the violence the employers and scabs caused. He also threatened to call in the military to bust the strike if the workers didn’t go back to work.

The strike began to fall apart soon after. Teamsters leader Cornelius Shea didn’t really have a strategy to end the strike. There weren’t any bargaining sessions scheduled and the EA was uninterested in compromise anyway. The building trades went back to work in late May, weakening the action. The Teamsters took control of the strike from Shea. It looked like the strike would soon end. Bargaining took place in late May and early June and a lot of issues were settled. But the EA weren’t even the hardliners among employers. Textile firms unaffiliated with the EA refused to the terms. The strike continued.

What finally ended it was a weird series of charges and countercharges about bribery. John Driscoll was a leading agent of the employers. He claimed that he had been bribed by the leading employers of the city to take a hard line and force the workers out a strike. A grand jury heard this testimony on June 2. Driscoll also claimed that Teamsters leaders had also offered him bribes to end the strike. Shea and other labor leaders then made claims that various employers in the city had offered them bribes to strike their competitors and the employers accused the unions of demanding bribes as well. In this mess, control of the press mattered. Basically, the stories of the unions demanding bribes were played up and the stories of the employers’ bribes were erased from the story. The leader of the EA had Shea arrested for libel for the bribery accusation. This caused him and the Teamsters to pull out of the talks to end the strike completely.

The aftermath of all this was that public opinion turned against the union. Probably both sides were in fact corrupt. But only one really suffered. Neither Shea nor any other labor leader was convicted of bribery or anything else, but the damage was done. The workers slowly started returning to the job and by the end of the July, the strike was over. The EA basically won. The Chicago trade union movement was significantly weakened and the employers continued to roll back previously won union gains over the next decade. Half the Teamsters on strike were never rehired and many had to move out of Chicago to escape the blacklist. The Chicago labor movement wouldn’t recover from this loss until the 1930s. Meanwhile, Montgomery Ward would remain a hard-core bastion of anti-unionism long after most companies had acquiesced to the New Deal order.

This is the 352nd post in this series. Previous posts are archived here.