This Day in Labor History: March 31, 1921

On March 31, 1921, Brookwood Labor College was formed at a labor conference in New York to provide adult education for workers. This is perhaps the most influential of the labor colleges, an important piece of our labor history and one that saw a revival in the 1970s and 1980s.

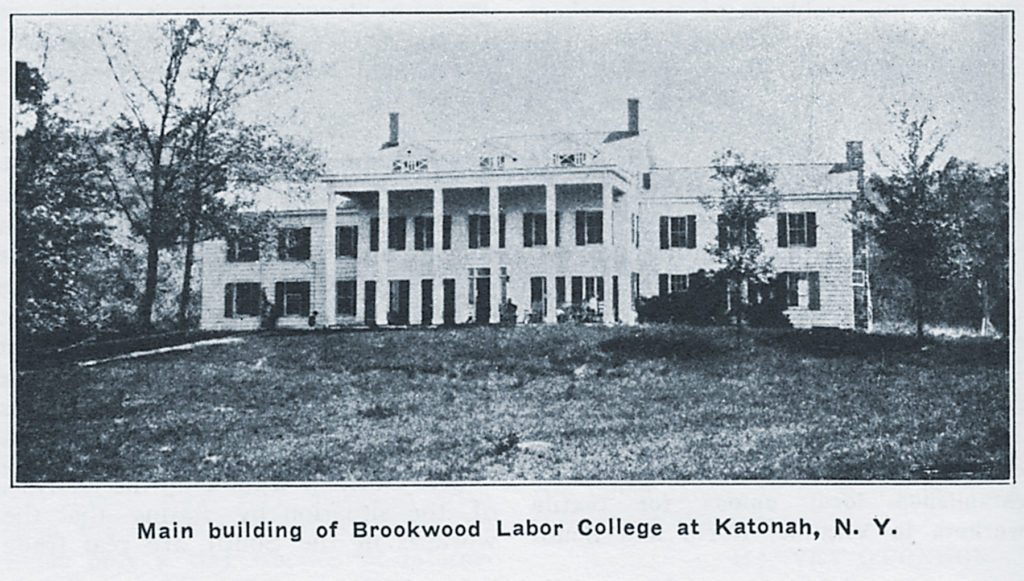

Around 1914, unions and reformers began deciding to create labor colleges in order to build class consciousness among workers, seeking to drive the violence of the streets into a channeled working class resistance through nonviolent means. That year, a rich clergyman named William Mann Fincke purchased a 53-acre resort in Katonah, New York. After the steel strike of 1919, brutally crushed by the mine owners, Fincke and his wife Helen decided to give over the land to provide a school for workers. But they didn’t provide much money for it and by 1921, it was falling apart.

On March 31, 1921, a meeting took place to transfer control of the estate to the labor movement. Leaders in this process were American Federation of Teachers president Abraham Lefkowitz, Women’s Trade Union League president Rose Schneiderman, William Z. Foster, the socialist who had led the 1919 steel strike, and the radical minister A.J. Muste, who would run Brookwood, under the heavy influence of his good friend, the education reformer John Dewey. This was the left wing of the labor movement, but other more moderate labor leaders would play a key role in the leadership, such as John Brophy from the United Mine Workers of America. The school was funded through the tuition of the workers who took classes there, generally paid for by scholarships from the workers’ union.

The classes were mostly in the labor humanities and social sciences. This was about training in the labor movement, but also about training workers to be well-rounded people ready to make a difference in society and these leftists realized that literature, history, and philosophy were critical issues in helping that happen. Alas, if only people took those subjects as seriously a century later. The full course was a two year program in labor history, contemporary politics, sociology, economics, English literature, foreign languages, and world civilizations. The idea was that graduates would become organizers for the next generation of labor. Thus, students were also trained in public speaking and labor journalism. Later in its existence, it also created the Brookwood Labor Players, a theater troupe that toured the nation in the 1930s putting on left-leaning plays. Most of the students came from the northeast, especially New York City, and most had not graduated from high school. Among the most prominent students of Brookwood included future United Auto Workers leaders Walter and Roy Reuther, the legendary civil rights organizer Ella Baker, and the amazing feminist and civil rights leader Pauli Murray.

Not surprisingly, the left leaning nature of Brookwood ran headlong into the political conservatism of the American Federation of Labor. That it was at a time that the American labor movement was getting creamed by the anti-union assault of the 1920s did not help. The AFL was interested in worker education but was highly suspicious of left-leaning education. That was led by William Green, who was about to take over the federation upon the 1924 death of Samuel Gompers. Green urged unions to spend more on worker education but frequently denied leftist organizations any support. But even while Gompers was alive, Brookwood came under AFL attack, when he claimed in 1923 that it was controlled by an interlocking group of pacifist and revolutionary organizations. Brookwood wasn’t too concerned about this as it was independent of the federation, but in 1926, the attacks began again under Green. That was because Brookwood was the most successful of the labor colleges. When Muste started a $2 million fundraising campaign to double the size of the enrollment, the AFL feared he would flood the federation with leftist organizers who would challenge the dominant political conservatism of the American labor movement. William Green and John L. Lewis started redbaiting and investigating Brookwood.

It didn’t help when Muste used modern psychology to describe the position of workers in American society, writing in Labor Age that workers needed to be “psychoanalyzed…to have their thoughts and feelings laid bare before their own eyes. They know too many things that are not so, they are living a dream world, not a real world, in a world of fears, illusions, fairies, and bogey men.” Green ordered Matthew Woll, one of this top lieutenants, to lead an official investigation into leftist activities at Brookwood. While the official report has never been found, evidently it claimed that all the faculty at Brookwood were leftists who were pro-Soviet and anti-religion and that the AFL should cut all ties. The 1928 AFL Convention denounced Brookwood with a sham trial that led to a lot of public criticism, including from John Dewey. This didn’t kill Brookwood, but it was heavily damaged as the AFL discouraged member unions from sending workers there. At the same time, Muste himself was moving significantly to the left and wanting to move more directly into training leftists to bore into unions and organization on an industrial basis, which he would engage in personally in the 1934 Toledo Auto-Lite strike. Muste and others formed the Conference for Progressive Labor Action in 1929 to push for this revolutionary activity that was not exactly communist but did call for the overthrow of capitalism. This resulted in declining support for Brookwood even from much of the left.

To make matters worse, the Great Depression decimated funding for Brookwood. Muste finally left in 1932 after moving college resources toward the CPLA, leading to a desperate fundraising drive to keep it open. It had pretty strong enrollments into the 1934-35 academic year, but bad numbers in the next two years led to its closure in 1937.

Brookwood may have failed as an institution, but it trained hundreds of workers over its history, many of whom became leaders for the future. It pioneered the idea of labor education and became known as “labor’s Harvard.” The novelist Sinclair Lewis, a big supporter of Brookwood, wrote that it was “the only self-respecting, keen, alive educational institution I have ever known.” Moreover, it served as an inspiration for decades. In the 1970s, a new generation of labor colleges developed out of the reformist impulses of the period that trained workers in a huge variety of programs. To some extent, these are still around today, connected with universities, although they are frequently under attack from budget-cutting administrators and are now often more about training people in human resources than in labor education.

This is the 349th post in this series. Previous posts are archived here.