Good news: Author of Imperial College study massively revises predicted deaths downward after UK adopts intensive suppression efforts

Last week (which seems like a couple of years ago now), the Imperial College of London published a study that predicted 500,000 and 2,200,000 deaths from coronavirus in the UK and US respectively if no mitigation measures were taken, and roughly half that many with the most effective mitigation measures available (ETA: Note that what the authors defined as optimal mitigation were fairly modest measures). Lowering the death rate much below that, the study predicted, would require a year to eighteen months of very intensive suppression measures.

Now the lead author of that study seems to have revised those estimates sharply, apparently in part because of the UK’s subsequent adoption, and planned adoption, of intensive suppression efforts:

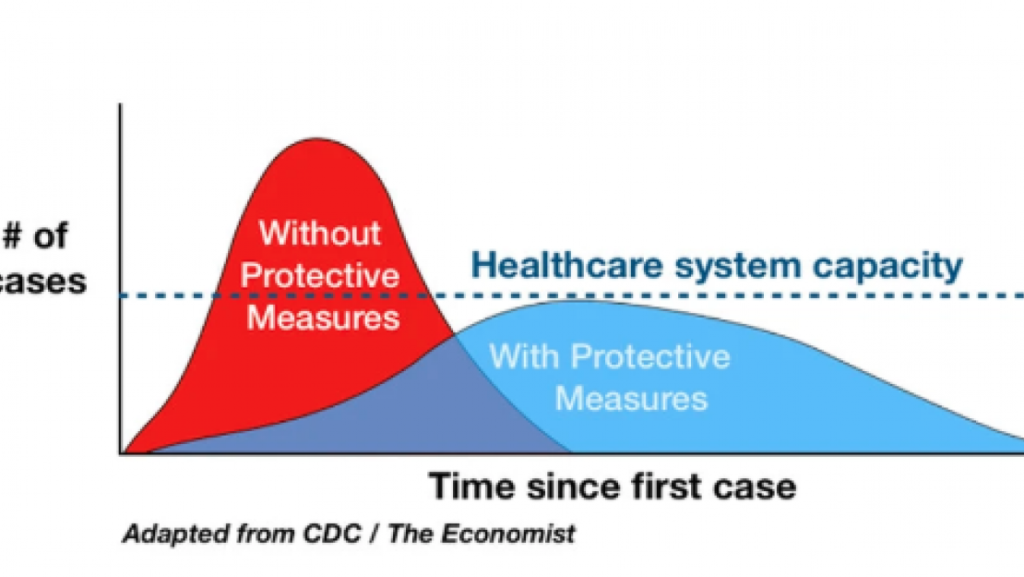

[Neil Ferguson] said that expected increases in National Health Service capacity and ongoing restrictions to people’s movements make him “reasonably confident” the health service can cope when the predicted peak of the epidemic arrives in two or three weeks. UK deaths from the disease are now unlikely to exceed 20,000, he said, and could be much lower.

The need for intensive care beds will get very close to capacity in some areas, but won’t be breached at a national level, said Ferguson. The projections are based on computer simulations of the virus spreading, which take into account the properties of the virus, the reduced transmission between people asked to stay at home and the capacity of hospitals, particularly intensive care units. . .

New data from the rest of Europe suggests that the outbreak is running faster than expected, said Ferguson. As a result, epidemiologists have revised their estimate of the reproduction number (R0) of the virus. This measure of how many other people a carrier usually infects is now believed to be just over three, he said, up from 2.5. “That adds more evidence to support the more intensive social distancing measures,” he said.

His comments come as a team at the University of Oxford released provisional findings of a different model that they say shows that up to half the UK population could already have been infected. The model is based on different assumptions to those of Ferguson and others involved in advising the UK government.

Most importantly, it assumes that most people who contract the virus don’t show symptoms and that very few need to go to hospital. “I don’t think that’s consistent with the observed data,” Ferguson told the committee.

There are some ambiguities here: Perhaps the measures already being undertaken in the UK themselves qualify as the sort of maximally effective intensive suppression the study’s authors had in mind? (If so, is the estimate of no more than — and perhaps far less than — 20,000 total UK deaths based on the assumption that intensive suppression efforts of this type stay in place for a year or more, as per the original paper?)

Nevertheless, it seems clear the authors are moving toward the hypothesis that the overall level of infection from COVID-19 is already far higher than their original model assumed. This would of course suggest that a much higher percentage of cases are actually mild or even asymptomatic, although [ETA: Bijan Parisa points out that this isn’t true.] Note that Ferguson still rejects the Oxford study’s hypothesis that the virus may have already infected something close to half the UK’s population.