A reminder that we still don’t know what the hell is going on

The most important gap in the medical and scientific community’s knowledge regarding COVID-19 remains this: The prevalence of the virus in various national populations at any moment remains almost wholly speculative.

The media routinely report that there are, for example, 54,968 cases of the virus in the US (the figure as I type this). It’s certain that the real number is far higher, because only a very tiny percentage of the population has been tested. The number of tests administered so far is hard to pin down with any accuracy, but the government claimed yesterday that about 300,000 people had been tested, leading Donald Trump to boast, absurdly, that the US had tested more people than South Korea (The population of the USA is six and a half times larger than that of South Korea. We’ve tested less than one out of every 1000 people).

But how much higher? No country, as far as I can tell, has to this point done any sort of randomized population-wide test of prevalence. Obviously tests have been in critically short supply almost everywhere, and it’s a rapidly moving target, so this in itself isn’t surprising. Nor, even more crucially, has an antibody test been developed yet to detect who has had the virus and recovered from it. Not only do we have no idea who has the virus now: we have no idea how many people had it and fought it off.

Since law professors are required by the terms of the Langdell-Sunstein Compact to pretend to be experts on the public crisis of the moment, no matter what it might be, let me throw out a couple of amateurish impressionistic observations:

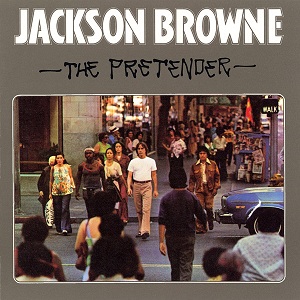

(1) A strikingly large number of celebrities and semi-celebrities have tested positive (Just in the last few hours this has included one of my favorite singer songwriters and one of my least favorite Princes of Wales). If you randomly named 6000 people (about one in 6000 Americans has tested positive as of right now) the chances I would know any of them would be quite slim, yet I know OF probably 50 people who have tested positive. Obviously this is because famous people get tested, unlike everybody else.

(2) A doctor friend told me that the ratio of people who presented at a Colorado hospital with COVID-19-like symptoms and the subset of those people who were being tested was dozens to one.

Now we have this, from what seems to be some leading theoretical epidemiologists in the UK:

The Oxford research suggests the pandemic is in a later stage than previously thought and estimates the virus has already infected at least millions of people worldwide. In the United Kingdom, which the study focuses on, half the population would have already been infected. If accurate, that would mean transmission began around mid-January and the vast majority of cases presented mild or no symptoms.

The head of the study, professor Sunetra Gupta, an Oxford theoretical epidemiologist, said she still supports the U.K.’s decision to shut down the country to suppress the virus even if her research winds up being proven correct. But she also doesn’t appear to be a big fan of the work done by the Imperial College team. “I am surprised that there has been such unqualified acceptance of the Imperial model,” she said.

If her work is accurate, that would likely mean a large swath of the population has built up resistance to the virus. Theoretically, then, social restrictions could ease sooner than anticipated. What needs to be done now, Gupta said, is a whole lot of antibody testing to figure out who may have contracted the virus. Her research team is working with groups from the University of Cambridge and the University of Kent to start those tests for the general population as quickly as possible.

To my lay eye, this theory seems elegant in its simplicity. The structure of the argument seems to be:

(1) Assume that a very large percentage of cases are asymptomatic or feature quite mild symptoms.

(2) As a consequence the virus therefore spreads exponentially for weeks before the first case is officially identified in a country.

(3) Since social distancing etc. kicks in only many weeks after the first case has been identified — which again was weeks after it actually appeared in the population — by the time it does the virus is already extremely widespread: so much so that mitigation and suppression measures may be having only limited effect.

(4) If all this is true, countries where the epidemic is currently raging may be fairly close to reaching some type of herd immunity. ETA: This assumes possessing antibodies confers immunity, at least for some time, which would be typical of this sort of virus, but would also need to be demonstrated empirically.

Of course this would be extraordinarily good news. It would mean that perhaps only one out of every thousand people who get the virus require hospitalization, because the vast majority of cases are either asymptomatic or very mild.

Testing the theory requires an antibody test, but my understanding is that this should be fairly straightforward to develop. Randomized population testing could then be carried out in short order.

One more tiny bit of potentially supporting evidence: the number of identified cases per day in Italy appears to be flattening, even though there’s a lot of evidence suggesting that Italy didn’t impose social distancing measures until the epidemic was very far along (some Italian doctors have suggested it could have been present in the population in December, which is probably true for the US as well), and a lot of the measures were adhered to only very loosely, at least initially.

Does this mean social distancing should be abandoned? Obviously not: this is at this point just a theory, and one that optimism bias impels us to believe. But it is — checks Section 3 subsection 27 of the Compact — a very plausible theory. We can all hope, or pray if you’re so inclined, that it turns out to be true.