This Day in Labor History: February 19, 1910

On February 19, 1910, the Philadelphia Rapid Transit Company fired 173 union members to bust a strike by its drivers, leading to a general strike and general uproar against this outrageous unionbusting, culminating in an all-too-rare victory for workers in the early twentieth century.

Streetcar workers often had it pretty tough in the Gilded Age, making the field one with strong union support from workers. In 1909, the Amalgamated Association of Street and Electric Railway Employees Local 477, the American Federation of Labor-affiliated union for streetcar drivers, wanted to win a contract for the Philadelphia drivers. This was not some radical union. In fact, the union went to the Philadelphia Rapid Transit Company, who owned the streetcar lines, and asked to work together on this issue, bringing the workers into the union movement in a respectable way without strikes.

But the response of most employers was as mouthbreathing anti-union against AFL unions as against the IWW or other radical unionism. The demands of the union were pretty limited. They wanted workers to labor only 9-10 hours a day, they wanted a 25 cents an hour minimum wage, the right to buy their uniforms from anyone they wanted instead of from the employer who inflated the prices to take back as much of the meager wages as they could, and union recognition.

So the workers went on strike in May 1909, angry at the complete dismissal of the PRTC to even meet with the union. As soon as that happened, the employer brought in scabs from New York. There were many transportation strikes and experts arose that specialized specifically in busting this sort of strike. So it wasn’t particularly hard for Philadelphia to find scabs. The people of Philadelphia hated these companies, as did many people around the nation toward their local streetcar lines. These companies were notorious for terrible service and domination over local politics, so public sympathy was with the workers. In June, the Philadelphia Central Labor Union, which is the antecedent to central labor councils today, threatened a general strike. This worked. The mayor intervened and the union and company came to a short-term agreement that raised wages to 22 cents an hour, a 10 hour day, the uniform demand, and even union recognition. But this was not to be a long-term peace. The PRTC immediately began to form their own company union and promoted those workers who joined it. It then refused to meet with Amalgamated-affiliated workers.

In December 1909, the Amalgamated decided to make new demands. Workers again wanted the 25 cent minimum wage. The company refused to meet with the workers and then, on January 1, 1910, unilaterally announced it would continue to pay the 22 cent rate while claiming to invest in worker welfare plans that were basically scams. A few days later, the company fired seven workers for refusing to join the new company union and pledging their loyalty to the Amalgamated. The union asked for arbitration but the company refused outright. So the union called for a strike vote. Around 95 percent of the workers voted to walk off the job, whenever union leaders thought that was their only option, but not immediately. The city’s mayor came out in favor of the company, saying that the workers were “semi-public functionaries” who needed to sacrifice for the city and its people. This is the same attitude that drives attitudes toward transportation strikes to the present, when even people who claim to be liberal will be outraged if subway workers strike and it inconveniences them for a few days.

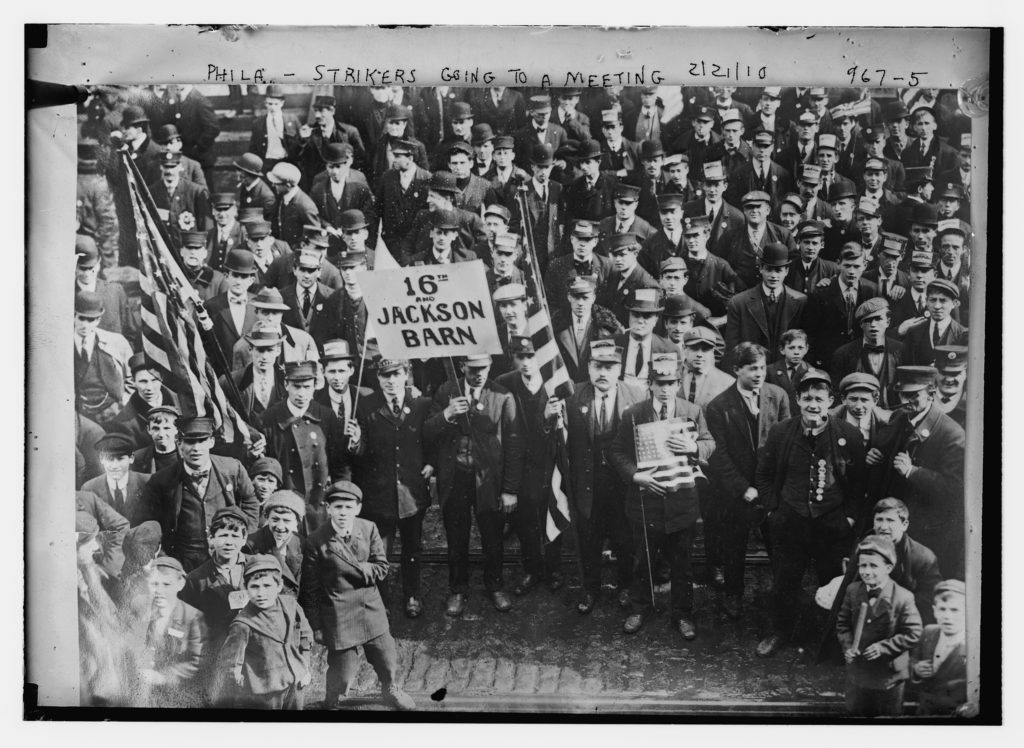

Over the next month, the two sides parried. AFL head Samuel Gompers got involved to urge arbitration. But the PRTC went all-in with the rhetoric about workers getting to “choose their own union,” which really meant being dragooned by the company into the company union. And then, on February 19, they fired 173 union activists. The Amalgamated leadership was left to their own discretion after the strike vote when the workers approved of it. Everyone was hoping for some kind of settlement, except for the company. This was the now or never moment. The strike began.

The mayor weaponized the city against the strike, sending out troops to protect the trolley cars on the first day of the class. Of the approximately 7,000 workers, 6,200 walked off the job. There was violence almost immediately. People threw rocks at the scab trolleys. One scab ran his trolley straight into a crowd blocking the track and was killed after the cab wrecked, though this may be an apocryphal story. An 8-year old boy died during an action where workers and supporters, which included many non-workers who hated the streetcar companies, destroyed a car. One trolley was set on fire after people kicked out the scab crew. At one point, people even wheeled dynamite out onto the tracks to note that they were serious. Probably half of the solidarity strikers, which numbered in the thousands and represented, as so many strikes during this era did, great anger at the domination of companies over all aspects of the life of the poor, were under 18 and therefore rowdy. When the mayor demanded volunteers to keep order, the Amalgamated offered the workers themselves, who would conduct the strike peacefully and prevent violence. But the mayor of course rejected this, not wanting to legitimize workers and preferring to kill some poor people and bust the union. Of course, the media wrote in purple prose about the attacks by evil workers on our brave police.

When the National Guard was mobilized to protect the scabs, the city’s unions responded by returning to the threat of a general strike. The idea of a general strike was not something to take lightly. The leaders of the labor movement in Philadelphia and the U.S. were not wild-eyed radicals. But the use of state violence against the strike changed the equation and they rightfully recognized the city’s response as a threat to all unionized workers. By early March, 140,000 people were striking in Philadelphia. This brought much of the city to a halt, though it was pretty inconsistent in implementation. Moreover, a women’s auxiliary formed as a solidarity organization with the strikers, many of whom were the husbands and fathers of these women. They attempted to hold big rallies, but were routinely denied permits, even though the organizer stated that the only thing men would be doing in this action was holding the babies so the women could march.

All of this finally forced the company to the bargaining table. Its strategy of starving the workers into submission largely failed in the wake of this amazing solidarity effort. The general strike ended on March 27 as negotiations began. The streetcar workers remained off the job until April 19.

Finally, the company agreed to most of the union’s demands. They agreed to pay the 25 cent wage. They rehired the strikers though without seniority, and they agreed for mediation on the 173 fired workers that precipitated the strike. No, they did not agree to recognize the Amalgamated as the sole bargaining agent for the workers, but this was still a big win for workers in the Gilded Age. The strike cost the company about $2.3 million. It also demonstrated to the forces of order than only mass violence could keep workers in check and they determined to respond in kind next time.

This is the 346th post in this series. Previous posts are archived here.