The True Infinity War

Much of our discussion of foreign policy in this country is broken. That’s for many reasons. One of them is that Americans see themselves as a fundamentally good country, which is utterly laughable the more you know about the nation’s interactions with the rest of the world, really through its entire history but especially since 1890. Now, I am very sympathetic to outrage at how the nation’s leaders keep us in the “infinity war,” as Samuel Moyn and Stephen Wertheim bemoan here. For obvious reasons, there are many reasons to continue fearing what Donald Trump is doing to the world and there are many reasons to be disgusted at the entire last 20 years of foreign policy in the Middle East, which was almost guaranteed not to work. Let’s look at the start of the article:

Now we know, thanks to The Afghanistan Papers published in The Washington Post this past week, that U.S. policymakers doubted almost from the start that the two-decade-long Afghanistan war could ever succeed. Officials didn’t know who the enemy was and had little sense of what an achievable “victory” might look like. “We didn’t have the foggiest notion of what we were undertaking,” said Douglas Lute, the Army three-star general who oversaw the conflict from the White House during the administrations of George W. Bush and Barack Obama.

And yet the war ground on, as if on autopilot. Obama inherited a conflict of which Bush had grown weary, and victory drew no closer after Obama’s troop “surge” than when Bush pursued a small-footprint conflict. But while the Pentagon Papers, published in 1971 during the Vietnam War, led a generation to appreciate the perils of warmaking, a new generation may squander this opportunity to set things right. There is a reason the quagmire in Afghanistan, despite costing thousands of lives and $2 trillion, has failed to shock Americans into action: The United States for decades has made peace look unimaginable or unobtainable. We have normalized war.

President Trump sometimes disrupts the pattern by vowing to end America’s “endless wars.” But he has extended and escalated them at every turn, offering nakedly punitive and exploitative rationales. In September, on the cusp of a peace deal with the Taliban, he discarded an agreement negotiated by his administration and pummeled Afghanistan harder than ever (now he’s back to wanting to talk). In Syria, his promised military withdrawal has morphed into a grotesque redeployment to “secure” the country’s oil.

It is clearer than ever that the problem of American military intervention goes well beyond the proclivities of the current president, or the previous one, or the next. The United States has slowly slid away from any plausible claim of standing for peace in the world. The ideal of peace was one that America long promoted, enshrining it in law and institutions, and the end of the Cold War offered an unparalleled opportunity to advance the cause. But U.S. leaders from both parties chose another path. War — from drone strikes and Special Operations raids to protracted occupations in Iraq and Afghanistan — has come to seem inevitable and eternal, in practice and even in aspiration.

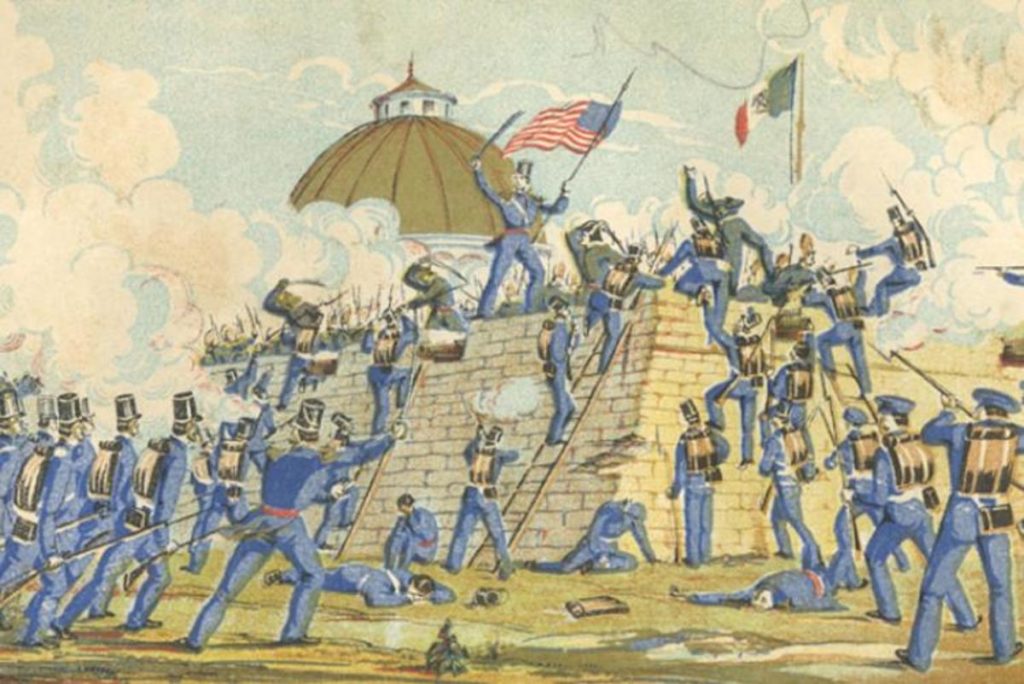

My problem with this isn’t that it’s wrong. It’s that it makes it sound like something new. The history of the United States is basically an infinity war against people of color around the world. That’s what too often gets erased. When I teach the history of U.S. Foreign Policy, as I am doing this semester, my class starts in the only sensible place: Native America. That’s because the dominant feature of our foreign policy in the 19th century was an infinity war against Native people, resulting in massive genocide. As John Marshall stated, the tribes were “domestic dependent nations” and thus had to be treated as quasi-foreign powers requiring treaties. That could also take on other forms when the nation chose to expand to extend slavery’s reach, most notably in the unjust and outrageous Mexican War.

When Frederick Jackson Turner bemoaned the closing of the frontier in 1893, he tapped into a general anxiety among the nation’s elites over the Anglo-Saxon future without this infinity war. Imperialism filled the gap and the unjust Spanish-American War and the genocidal Filipino-American War served the same function. Now, outright imperialism proved a bit too direct for hypocritical Americans who don’t like their crimes being so obvious. So the Dollar Diplomacy of William Howard Taft and Elihu Root, building on the Roosevelt Corollary to the Monroe Doctrine, took over and the U.S. engaged in a new form of infinity war, occupying Nicaragua from 1912-1933 and Haiti from 1915-1934, among many other invasions, including serving the direct interests of fruit companies. Much like the modern Middle East, the U.S. military engaged in a low-intensity but constant war against brown people who wanted control over their own nations and lives.

Most of the Cold War was fought in the same way. With tensions in Europe really quite stable after 1950, the infinity war moved to Asia, Africa, and Latin America, with horrible results for the people of Guatemala, Iran, the Congo, Vietnam, Cambodia, Nicaragua, Chile, and so many other nations. At times, this infinity war included U.S. troops, to truly disastrous results in Vietnam, but usually the U.S. outsourced its infinity war to locals through the CIA and military top brass. That could get extremely ugly–genocide in Guatemala, Iran-Contra, etc.–but few American troops died. Yet that hardly meant that the U.S. was not continuing to engage in an infinity war during these years.

After the Cold War, the infinity war moved to the Middle East and the War on Terror, in which we find ourselves enmeshed today. That killed 4,000 Americans in Iraq and scattered more elsewhere, but again, most of this today is outsourced and not many Americans die, even as huge numbers of Iraqis, Syrians, Yemenis, etc., do.

So for me, the infinity war isn’t just a problem with the nation since 9/11. It’s just another version of the war on people of color that has defined this nation’s existence since 1776 and which white Americans simply do not want to talk about. And that’s why statements like this from the Moyn and Wertheim piece really bother me:

Still, the pursuit of peace is an authentic American tradition that has shaped U.S. conduct and the international order. At its founding, the United States resolved to steer clear of the system of war in Europe and build a “new world” free of violent rivalry, as Alexander Hamilton put it.

Indeed, Americans shrank from playing a fully global role until 1941 in part because they saw themselves as emissaries of peace (even as the United States conquered Native American land, policed its hemisphere and took Pacific colonies). U.S. leaders sought either to remake international politics along peaceful lines — as Woodrow Wilson proposed after World War I — or to avoid getting entangled in the squabbles of a fallen world. And when America embraced global leadership after World War II, it felt compelled to establish the United Nations to halt the “scourge of war,” as the U.N. Charter says right at the start. At America’s urging, the organization outlawed the use of force, except where authorized by its Security Council or used in self-defense.

They completely handwave away the actual fundamental facets of American foreign policy history, all of which are relevant comparisons to the current situation, because they believe in the hypocritical rhetoric of Americans’ place in the world. Defeating that rhetoric and calling out American history as it is should be central of a left foreign policy.