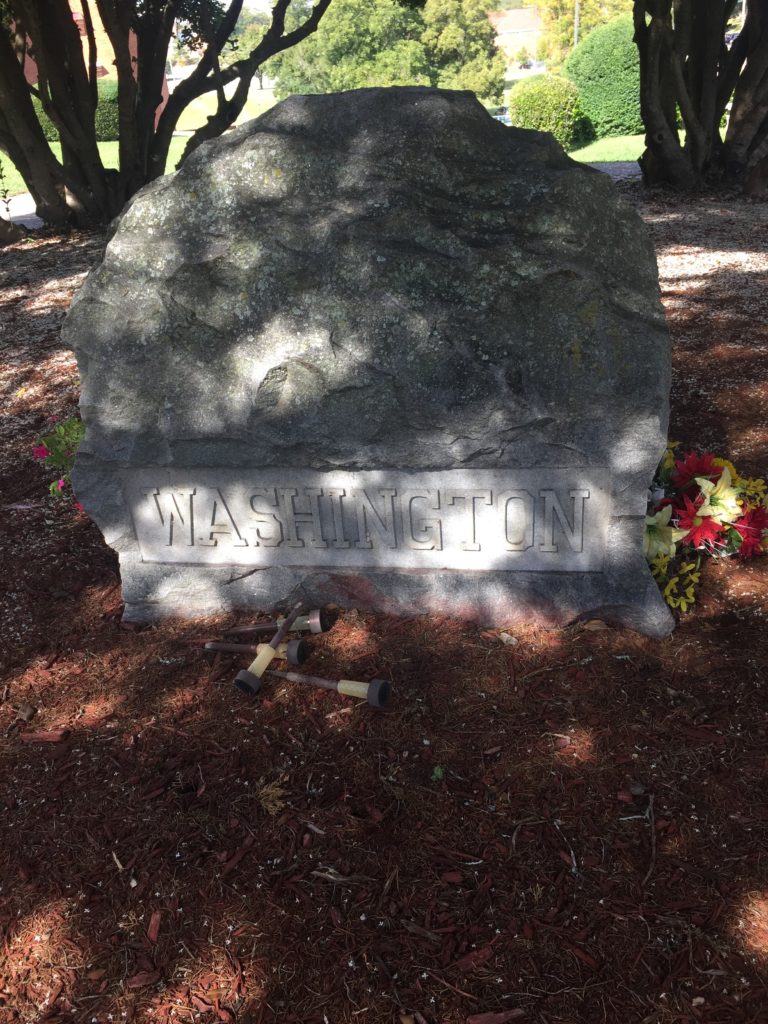

Erik Visits an American Grave, Part 596

This is the grave of Booker T. Washington.

Born into slavery on a Virginia farm in 1856, Washington spent the first nine years of his life as a slave on that farm. After emancipation, his mother moved he and his siblings to West Virginia, where her husband had settled after he had escaped from his master previously. That man was not his father. His mother was probably raped by a white man from a neighboring plantation, which was an incredibly common circumstance, something that is if anything underplayed in our public discussion of slavery. Like most former slaves, Washington had to work hard on a daily basis from a young age just to eat and contribute to the family income. He worked in salt furnaces and coal mines. Determined to get an education, he managed to get to the Hampton Institute in Virginia, one of the first black colleges in the nation, and also attended classes for awhile at what is now Virginia Union University. With more black colleges opening at the end of the Reconstruction period, young, talented, and ambitious people had an opportunity to rise in the world. Few were as talented and ambitious as Washington. And in 1881, only 25 years of age, Washington was recommended by the president of Hampton to be the first president of a new school, in Alabama, the Tuskegee Institute.

mWashington took this with aplomb, building this college up from fields into the most important black educational institution in the country. As he did so, he became a powerful force in the South. And a complicated one. Washington rose to that power by asking, nay demanding, that southern blacks give up all political ambitions, that they acquiesce to Jim Crow, that they focus on economic self-reliance over equal rights or justice. This was the core of his appeal. His famous, or perhaps infamous, Atlanta Exposition speech in 1895 laid out the fundamentals. Speaking to an audience of leading southern whites, he urged a compromise between the races. Whites would play a paternalistic role, funding Tuskegee and other similar institutions, and contribute to making Washington the leading “respectable” voice in the black community. In exchange, African-Americans would do nothing to challenge white supremacy and would play no role in politics. In fact, colleges such as Tuskegee, Washington argued, should not much bother with things such as civics or history or anything that would build up a political consciousness among the black population. No Plato or Socrates or Shakespeare for this population. Rather, agricultural experiments and basic skills the children of slaves could use in the southern economy, that was Washington’s belief. The so-called Atlanta Compromise infuriated northern black leaders such as W.E.B. DuBois and Ida B. Wells. In fact, it was DuBois who coined the Atlanta Compromise term, lambasting Washington for selling out the black community.

To be fair, Washington was operating in rural eastern Alabama as Jim Crow was being established. Out there, with lynchings ruling the day, it was extremely dangerous for any African-American to even live. In fact, as Washington’s stature and fame grew, even though it was on the foundation of racial acquiescence, there were many threats to lynch him as he traveled through the South. Any black person challenging power by simply being a known person was someone to be crushed for many whites. He was an incredibly brave and committed man, one responding to the reality of black life in the South.

And yet….Washington legitimately believed that he was the only reasonable voice of the black community. That doesn’t mean that he necessary personally believed in every aspect of the Atlanta Compromise. We know that behind the scenes he was working against segregation and giving money to legal challenges. As he was largely reliant on white donors to fund his school for much of its history, he had to play with a different face than he might behind closed doors (the first part of Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man is great on this with the donor taken to the black-owned bar and the response of “The Founder,” clearly based on Washington; Ellison was a Tuskegee grad and knew of what he spoke). But Washington was also incredibly jealous of any challenges to his leadership, by DuBois or anyone else and actively sought to destroy them. That led him to greater defenses, in private too, of the Atlanta Compromise and all the other compromises he made. About 15 years ago now, there were a couple of new biographies that sought to salvage the reputation of an increasingly disgraced Washington for modern Americans. As the reputations of DuBois and Wells and Douglass and Tubman and others have risen among post-1960s Americans, that’s come at Washington’s expense. But those biographies failed to revive him because what they showed was a very jealous, petty, and power-hungry man who increasingly did believe exactly what his critics accused him of.

Yet, Washington still had some power to negotiate white America in ways that other African-Americans did. It was a legitimate huge deal when he dined with Theodore Roosevelt in the White House. This has unfortunately given Roosevelt himself an anti-racist reputation, which is extremely undeserved. Roosevelt himself later regretted this meeting. But it was a groundbreaking thing at the time, even if it didn’t lead to anything concrete for African-Americans or move Roosevelt to do anything. Moreover, let us not forget Pitchfork Ben Tillman’s response: “The action of President Roosevelt in entertaining that n—– will necessitate our killing a thousand n—— in the South before they will learn their place again.” The subtlety of white supremacy on full display. This is what Washington dealt with in the South every single day.

Let’s also not understate Tuskegee’s role as a positive force for black America. Washington’s model was not designed to fight for black rights, it is true. But Tuskegee absolutely played a critical role in building black rural southern education. It trained people to go into their home communities where there was literally nothing for the ex-slaves and their children but poverty and violence and they brought back skills people could use in what limited education they could get. Through his wealthy white northern benefactors, Washington could raise massive amounts of money to build both primary schools and colleges. This may not have challenged the white power structure but it certainly gave a lot of people tools to help them survive and later to challenge the system if they chose, regardless of what Washington might have thought about it.

Yet, don’t underestimate what Washington’s compromising words can do today. In 1901, he wrote his famed autobiography Up From Slavery, which was at least as popular in northern white communities as with African-Americans, because it was basically the Atlanta Compromise in book form. Now, like most of you, and this is especially likely if you are married or have a long-term partner, I have extreme right-wing family members. So I’m at the table once a couple of years ago with some of them, and one, who is a genuine extremist, and talks to me about how he has been reading Up From Slavery. My first thought was that of a historian happy that someone is reading anything old. But then I immediately realized what this was. Someone in his wingnut media network was talking the book and Washington up as what black people should be doing today instead of running for office or protesting their murder by cops or wearing the baggy pants or whatnot. And I was incredibly depressed by this. It’s hardly Washington’s fault that his book gives succor to racists today. But his book does give succor to racists today.

Washington worked up until the end, even as his health declined at a pretty young age. He collapsed in New York in 1915 and was diagnosed with Bright’s disease. He had only one request: that he die at Tuskegee. He was able to travel by train back home and he died there, at the age of 59.

Booker T. Washington is buried at the Tuskegee Institute Cemetery, Tuskegee, Alabama.

This grave visit was sponsored by LGM reader donations. I thank you very much. I had meant to get this up before I left last weekend on a long grave jag through upstate New York to remind everyone of what they got for their donations, but I did not have time to finish it. So if you would like to help reimburse me for the expenses associated with that 16-grave visit, you can donate to cover them here. Other African-American leaders I could visit are Ida B. Wells, in Chicago, or W.E.B. DuBois, if you want to send me to Accra, Ghana. Previous posts in this series are archived here.