This Day in Labor History: October 15, 1970

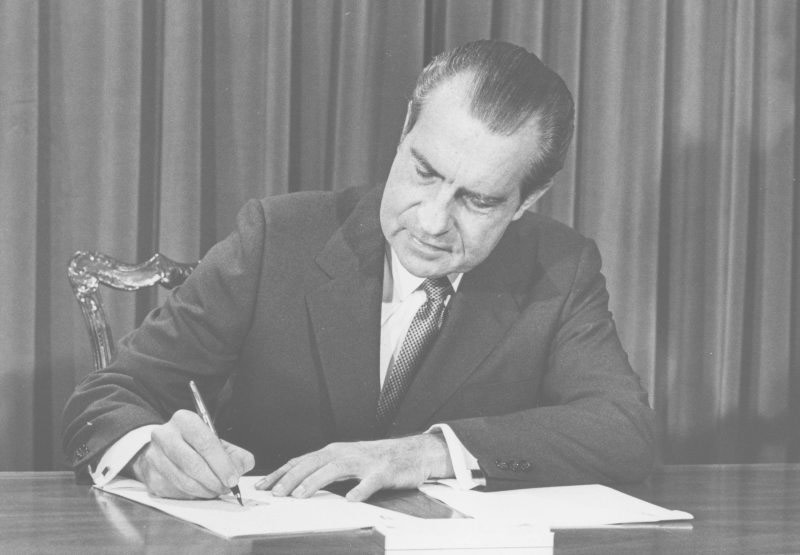

On October 15, 1970, President Richard Nixon signed the Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations Act. This act, like many anti-labor laws, had a veneer of a solution to a real problem, as there was indeed corruption in some unions, but also like these other laws loaded it up with a number of tools useful for employers to harass clean unions too.

Like any large organization with significant financial reserves, unions can sometimes end up with corrupt leaders. Sometimes unions, particularly some trades and longshoremen locals, were fully mob-influenced. Sometimes people who seemed like good people get corrupted by access to funds. It’s a problem, though significantly less so today than through most of the twentieth century. The UAW leadership has been accused of misappropriation of funds for lavish meals and travel. That’s really bad. It’s also child’s play compared to the actions of the old mobbed up unions.

It’s hardly news that organized crime was a big part of twentieth century urban life, to an extent significantly more than today. That influenced all sorts of parts of life. So laws to fight this don’t seem unreasonable. The RICO Act gave the government new rights to charge someone with racketeering if they were accused of a wide variety of crimes. It allowed the government to seize assets and is intended to force defendants to plead guilty of lesser charges to avoid the asset seizures. Over the years, it’s been used against all sorts of organizations–the actual mob, motorcycle gangs, corrupt government officials, Michael Milken. And unions.

Labor racketeering largely revolved around the sweetheart deals corrupt leaders would force on membership, on which they would personally benefit. Another common issue had to do with strike insurance funds that could be raided and other misuse of funds. These things were pretty hard to prove before RICO created the standard of repeated violations of racketeering laws that made individuals vulnerable to the new law.

From the very moment it was passed, a lot of people noticed how RICO statues were used as a labor-busting tool. Part of the law allows for civil RICO suits if someone thinks the organization is engaged in an enterprise that creates racketeering activity. But what does that even mean? With the help of anti-union judges, employers began filing spurious RICO suits.

Other union laws did not have nearly the expansive reach into what unions do–not Taft-Hartley, not Landrum-Griffin, not Norris-LaGuardia. Violations of Taft-Hartley could contribute to RICO prosecution, such as what happened to the International Longshoremen’s Association Local 1814, where the corrupt officials had their bribery payments covered under RICO, but not Taft-Hartley. This was one of the first uses of RICO against a union, focusing on the leadership of a particular corrupt local. In this case, it was a clear case of a couple of union leaders in a notoriously mobbed up union figuring out ways to steal money and enlist other officials in the scheme. This is the kind of thing RICO is actually useful for. When this happened, the courts would place a union under trusteeship. This was a practice with some roots in the 1930s and useful in eliminating corrupt leadership and giving union members the chance to create an honest local democratically.

It was the Teamsters which received the real brunt of RICO law. That union was riven with corruption in the middle decades of the twentieth century. And it held such enormous resources that placing it under trusteeship was the equivalent of the government doing the same thing to a large county. In 1986, IBT Local 560 was placed under trusteeship. This was an incredibly corrupt and mobbed up local involved in several murder of union members. The original trustee named by the judge only got rid of top leadership. When the judge decided that the shop stewards were basically machine men, he got rid of the trustee and named a much harsher one.

But after 1985, RICO prosecutions rose, probably because the fines rose and incentivized more prosecutions. That RICO is an incredibly complex act does not help. Instead, as judges have a hard time getting their head around all the facets of it, it opens the door for corporate lawyers to weaponize it. In 1988, the government went after the entire Teamsters. This was a vast expansion of RICO’s reach, one that far beyond the law’s original intentions. But this also opened the door for Teamsters for a Democratic Union to win the union democracy they wanted, which saw the election of Ron Carey, who, unfortunately, himself ended up getting busted for financial irregularities and which then paved the way for Hoffa Jr to take over, where he remains today.

All of this, well, OK, maybe it is justified. Sometimes it certainly was. The problem is the private civil suits under RICO. In 1991, Randy Mastro, Deputy Chief of the Civil Division of the Office of the U.S. Attorney for the Southern District of New York, wrote a remarkable article laying out how companies could use RICO to finish the job that the government had started. With nearly official sanction by a pretty high ranking legal office, employers didn’t need much convincing to do so. Because of treble damages and the possibility of the unions having to pay legal fees, companies were especially excited. Since then, and really since a bit before then, there’s been an explosion of civil RICO legislation, at least through the 1990s. One suit involved a construction company that a union was picketing. Even though there was no corruption involved, the company still filed a RICO case, claiming damages to its business it hoped to recoup. Blasting open the RICO Act’s boundaries, because there had supposedly been threats of violence, a court found for the company, even though there wasn’t even the slightest attempt to connect this kind of case to Congress’ intentions.

That continues today. For example, I know a long-time union organizer who had to appear before a RICO suit simply because the union this person works for had engaged in a corporate campaign to harass the company. There was no violence, there was no corruption. But it wastes time and money of the union. Here’s a RICO case in Boston that went to trial earlier this year that left the judge pretty skeptical–the issue at play was displaying Scabby the Rat! Ultimately, RICO is too vague and interpreted too broadly by the courts to favor employers to be a fair law. It should be overturned and a very specific law about corruption enacted. I’m sure that will happen once I get my flying pony.

I borrowed from Steven T. Ieronimo, “RICO: Is It a Panacea or a Bitter Pill for Labor Unions, Union Democracy, and Collective Bargaining,” published in the Hofstra Labor and Employment Law Journal in 1994, to write this post. This sort of deep dive on legal matters is a bit out of my wheelhouse, so forgive any errors of understanding.

This is the 333rd post in this series. Previous posts are archived here.