The Big Squeeze

This is really good on the fundamental problems putting even families with decent middle class incomes in an increasingly tenuous position:

The neoliberal era has scored American households cheaper groceries and electronics. But it’s also enabled extractive interests in the health-care, housing, and higher-education sectors to bleed middle-income families dry.

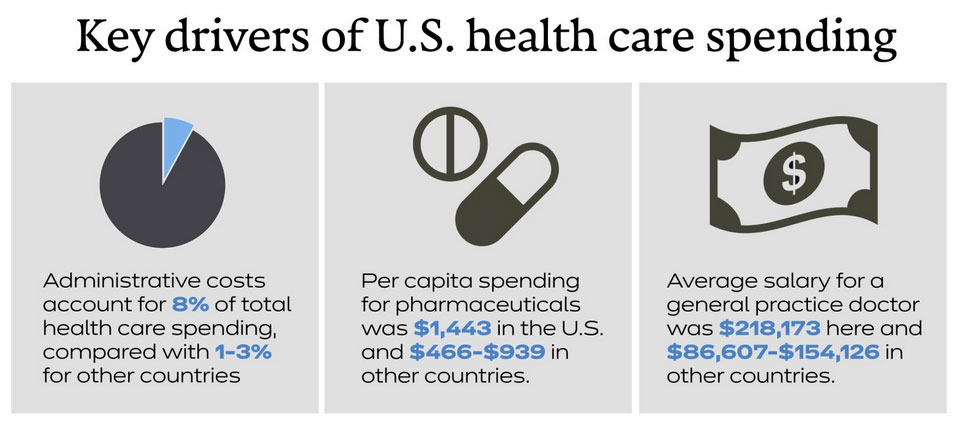

The health-care industry may be our economy’s most ravenous parasite. Due to our central government’s exceptional refusal to combat rent-seeking in the medical sector through price controls, the United States spends several times more than similar nations on health-care administration, pharmaceuticals, and physicians’ salaries. In return, Americans enjoy the 29th best health-care system in the world (just behind the Czech Republic’s), according to The Lancet.

To appreciate just how thoroughly we’re being ripped off, consider our neighbors to the north. In 2018, Canada spent roughly 11 percent of its GDP on health care, which was enough to provide all of its citizens with premium-free access to the world’s 14th-highest-performing health-care system. That same year, the United States spent roughly 18 percent of its GDP on health care — which, in our system, was not sufficient to provide any form of insurance to nearly 30 million Americans, nor to prevent more than 50 percent of our people from delaying or forgoing medical care due to affordability concerns.

A common misconception about the American political economy is that U.S. workers are lightly taxed. The Europeans may have a plusher safety net, the story goes, but at least we get to keep more of our take-home pay. But this is only true if one regards health insurance as a discretionary expense, which is not how the vast majority of adults in developed countries see it.

[…]

In other words, the American middle class is already taxed like Europe’s. But instead of buying us universal health care and other forms of social protection, our paycheck deductions go toward sustaining redundant private-insurance bureaucracies, Big Pharma’s high profit margins, and American doctors’ extraordinary salaries. We aren’t choosing to put “small government” above social welfare. We are choosing to be ripped off.

And the sick irony is that the massive amount of rent-seeking in the healthcare system makes comprehensive reform more difficult. Powerful lobbies — not just insurance interests but Big Pharma and practitioners — have a huge vested interest in the status quo, and it also makes the classic strategy of getting quiescence by offering a better short-term deal to some vested interests both effectively impossible and highly undesirable (whatever the relative percentage of taxes and premiums, health care costs are already far too high; we shouldn’t be looking to increase the pool.) It’s a very, very difficult problem.