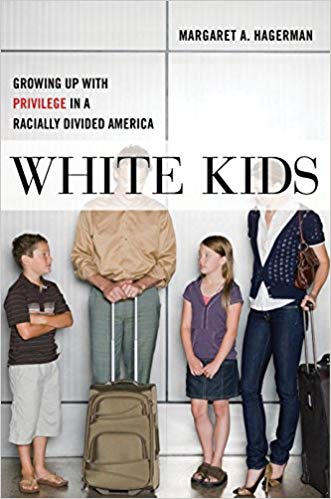

White Kids

Margaret Hagerman’s White Kids: Growing Up with Privilege in a Racially Divided America is simply put one of the best books I have read in years. Hagerman, a sociologist, spent time with elementary school children in the Midwest (obviously the Madison suburbs despite the weird sociological convention of changing the name of the place you are studying while providing all the correct demographic data for it) and talked to them about how they were already thinking about race. She talked to their parents too. And what is disturbing is that by the time young wealthy white kids are 10 years old, they already have quite sophisticated ideas about race that reflect serious white privilege. That is true whether they come from liberal or conservative families. This of course reflects the fact that white parents will tell children that their schools are “good” or “bad” depending on race. I reviewed the book for Boston Review.

Hagerman explains that children’s racial ideologies are shaped in part by conversations among their parents and friends about the quality of schools. When exposed to conversations that evaluate various districts in terms of crime and lost educational opportunities, they are astute enough to detect when “good” is equated with “white.” And likewise that “bad” schools are those with large numbers of black children, where students are said to be loud and unruly. Race thus gets conjoined with normative ideas of respectable behavior, safety, and educational opportunity.

Of course, the problem here does not rest with the children. By and large, white people simply do not have serious conversations about race. As Hagerman documents, many white parents become uncomfortable when discussing racism. Victoria, a wealthy conservative, told Hagerman: “Race isn’t really a part of my children’s experience, so we don’t really talk about it. While some people try to play the race card, things are pretty much equal nowadays.” She then added, “I guess there will always be those who want something for nothing.” Hagerman documents many cases where a superficially color-blind racial ideology papers over a deeper aversion to serious discussion of inequality and outright hostility toward policies such as affirmative action.

And it is hardly better in the schools. Often educators, uncomfortable with discussions of race and untrained in how to teach about it, instruct that any talk of race or racial disparity is itself racist—or at least this is the lesson many children internalize. This silencing of racial discussion allows differences to fester and harden. In such an environment, the term “racist” becomes little more than a joke insult for students to lob at one another, leading one school to go so far as to ban students from using the word. This is a disheartening symptom of the failure of the nation to respond to the resurgence of white nationalism with terminology that accurately describes it.

After all, how different is the definition of “racist” used by most white adults? Is it not mostly treated as an insult voided of any semantic or evaluative import? In politics as much as in private life, bad actors loudly proclaim that they are not racists, as if whether you are or are not is a matter of your own opinion about yourself. The only “racism” many will even deign to acknowledge is the racism supposedly directly against whites. Such claims of so-called “reverse” racism would be absurd if they didn’t deepen the impact of actual racism.

This is not only a problem on the right. On the left, white liberals are prone to discussing racism as though it never touches down into their daily lives and choices. It has nothing to do, for example, with the choice many make to send their children to nearly all-white schools: they are just doing what is “best for their children.” As if, in a society dominated by white supremacy, what is best for one’s children and racial logic are mutually exclusive. One of Hagerman’s key points is that racial ideology is something that falls on a continuum and manifests differently in different sorts of parents—ranging from outright racism, at one extreme, to removing your child from a bad school to give them more opportunities, on another. But all of these choices help stack the deck against students of color who are left behind.

Repeatedly, Hagerman demonstrates how wealthy white liberal parents either fail to see their role in de facto segregation or excuse it away. Even in the most left-leaning towns Hagerman studies, white parents say they value diversity and know that raising their children surrounded by other rich kids—even if some of them are people of color—reinforces racial and class divides. But in the same breath, they regretfully note that there is nothing they can do because they have an obligation to give their children the best education possible. As one parent tells Hagerman, she doesn’t want to make her child a “guinea pig.” The mother knows white flight undermines the idea of an equal education, but what can she do? In one telling anecdote, a father who tells Hagerman how much he loves Michelle Alexander’s The New Jim Crow (2010) still sends his children to private schools because public schools can’t give his kids everything he thinks they need. These parents claim to want diversity for their children, but in practice opt out of the public goods that resemble the diverse spaces they crave.

Hagerman includes a chapter on the compensatory strategies parents use to expose their children to the diversity they do not get at school—mainly volunteer work and international travel. She concludes that most of these only reinforce white privilege—encouraging white students to develop an ideology of their own special power to change the world. In Hagerman’s words, the result is “kids who can speak fluently and critically about race and racial inequality in the United States but who simultaneously believe they are better and more deserving than anyone else.”

Reading this book also allowed me to do something I’ve wanted to do for a long time: discuss and publicize the racism of the sector of white liberal LGM commenters who hate my education and race posts in a larger forum.

In addition to my day job as a history professor, I write for the liberal blog “Lawyers, Guns, and Money.”I grew up in a white working-class family and went to public schools in a struggling Oregon logging town in the 1980s and early 1990s. As such, I am a passionate defender of the potential of public schools to improve the lives of working-class children. I often blog about the intersection of race and schooling, as well as my outrage over the systematic gutting of the public education system alongside the rise of charter schools. In some of my posts, I argue, as Hagerman does, that the choices whites make for their children reinforce racial inequality. The fury these posts generate among commenters, who as a whole are upper middle-class white liberals, far surpasses the ire provoked by anything else on the blog. Many respond with outrage to the idea that anything they do for their children is racist, or that white supremacy shapes the options available to them, even as they and their children benefit from it every day.

The rhetorical backflips readers undertake to avoid the substance of this critique is often remarkable. Because I do not have children (Hagerman does not either), I have been repeatedly told that I have no right to discuss these issues. This sort of argument is hard to imagine in other contexts. Should I not argue for prison reform because I don’t know anyone in prison, or not argue against the Iraq War because I do not know Iraqis?

Commenters also often fall back on the argument that they have a responsibility to protect their children and offer them the best opportunities. But in arriving at those judgments, parents rarely consider that, as Danielle Allen has argued, public education is, above all, about educating good citizens. Generally this is something that public schools, as microcosms of the public sphere, do better than private schools. Specific job-related skills are easier to acquire later in life than are empathy, tolerance of different cultural traditions, and the capacity to function smoothly in a multicultural society.

Finally, there is a tendency for commenters to frame schooling as a collective action problem. Yes, a single individual refusing to drive will not make an appreciable difference in carbon emissions; climate change is a problem that must be solved at scale. But education could not be more different: individual parents do have a huge impact on individual schools and districts. Little can do more to reform schools than the active participation of parents. It is a horrible irony that large-scale divestment from public schools is being carried out by a generation of parents ardent about volunteering in schools. Fundraisers, after-school activities, and sports teams take tremendous amounts of time, energy, and financial resources from many parents I know. Imagine if all these hours benefitted not only individual children but were invested in rebuilding a public good.

White people have to take responsibility for their own privilege. Hagerman recommends self-reflective questions, and she is right to do so. But we also need more direct engagement of whites with other whites. It cannot be up to people of color to demand equity for themselves. Whites have to challenge each other about the ways their lives reinforce white supremacy. A key component of that must be for white parents to refuse to add to our nation’s racial disparity in how they raise their children.

My language was significantly toned down in the editorial process. But the point remains clear. And White Kids is as astounding book that should challenge each and every one of you if you actually want to do something about racism instead of just talking about Republicans and wishing things were like they were under the Obama administration, when things were still horrific for tens of millions of Americans.