This Day in Labor History: September 27, 1875

On September 27, 1875, striking textile workers in Fall River, Massachusetts engaged in a bread riot as the workers were forced to return to their job or face shipment to the state’s poor farm. This strike and incident was a sign of transitioning gender roles among the British immigrant workers who had come to Fall River and of the cultural divides between workers and management that marked the era.

After the U.S. Civil War, British trade unionists sponsored a massive emigration from Lancashire to Fall River. The idea was to find new opportunities for skilled unionists by sending them somewhere else, taking both British skill and British militancy with them, while maintaining high wages at home by reducing the oversupply of workers and avoiding industrial strife.

But life in Fall River was no paradise. The textile factory owners did not see skilled workers. They saw insubordinate unionists. Fall River was an especially awful place to work. The owners there used the cheapest possible cotton and paid the lowest wages in New England. They also sought to break down their workers by forcing them into ever more strenuous work, producing huge amounts of highly inferior cloth with lots of flaws that the printing process would conceal. For the English men who had moved there, textile work came with manly pride in a job well done. In their vision, workers and masters had well-established duties that included employers being willing to negotiate with reasonable unions. That was, uh, not shared by the Fall River employers. Moreover, the duties of employees, in this worker system, was a daily deference to the bosses that reflected the British class system. So they would doff their caps and the like. But the Fall River employers, having no idea what this meant, assumed these were extra docile workers.

Labor tension built as the two sides routinely misunderstood each other. The first major strike that included the British workers was in 1870, in response to a wage cut. The spinners, an all-male workforce, walked out and offered to compromise. The employers refused to even acknowledge the existence of a labor organization. Instead, they recruited thousands of replacement workers from the other impoverished towns in the area and busted the strike. The strikers though wanted to maintain the respectability of the union and so there was only one attack on a scab and that was probably not by a spinner. But after two months, the spinners had to return to the mills with whatever they could get. The workers continued to organize, but in secret, while the mill owners tried to find all the strike leaders and blacklist them. At the same time, the employers went to Lancashire to recruit more workers. British employers warned them of the workers’ militancy, but with so much poverty in New England and Fall River controlled the nation’s print cloth market, they figured they could easily bust any worker activism.

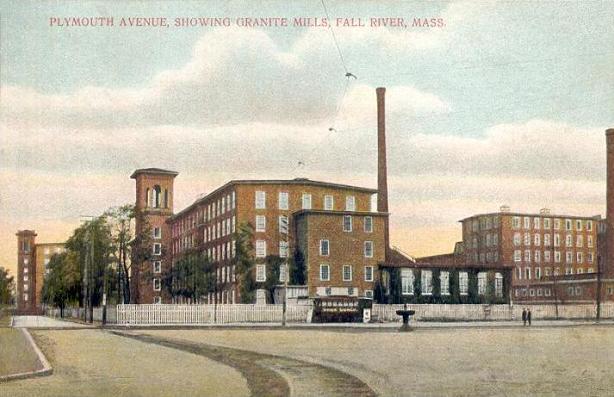

The Panic of 1873 made conditions worse for the workers. Wages were cut and workers were forced to labor even harder. Becoming beasts of burden not only cut against their union pride but on the connections they made between work and proper manly bearing, which included the right to spin according to their craft and making enough money to support their families. The low wages meant they were forced to cut back on their legendary appetites for beef and beer, foods they associated with their manly culture. These men did work tremendously hard and the calories and carbohydrates were critical to them. The owners tried to force salmon on them instead of beef, a common cheap replacement at the time, but the workers completely rejected this. Then, in 1874, the Granite Mill caught on fire. Workers blamed management. Part of the spinners’ culture was to oil and clean their machines. But employers denied them this by setting the piece rate so low that they would have no time to do so. Over twenty workers died. It started when a spinner’s unoiled machine produced a spark that set some cotton waste on fire. Once again, workers blamed management. And once again, management was utterly indifferent to dead workers, though irritated about the cost of rebuilding the factory.

By early 1875, Fall River mills were back up and spinning at full capacity, but the conditions for the workers were still awful. The desperate clinging to respectability made the male spinners reticent to strike. So it was the women workers who started to organize after men were going to accept another wage cut. The women suspended work at the three affected mills while allowing the other mills to keep running and having the workers all contribute to the collective strike fund. It worked and the lost wages were restored. By January 16, the women were openly challenging the manhood of the male workers. The men responded by presenting their demands to their employer the next day. When he blew them off, they joined the women on the picket line. Women were the absolute leaders by this time, taking authority from men who were discouraged by their many losses over the previous years. Women started appearing on speaking platforms, urging the workers to action. They were mostly weavers and their initial successes led a movement to create a broader region-wide set of demanded rates for weaving that would undermine strikebreaking.

In the summer of 1875, the Fall River owners decided to destroy their smaller competitors in Massachusetts and Rhode Island by lowering wages again. The women weavers once again took the lead. On July 31, they decided not to strike but collectively take a one-month “vacation.” This was very effective and disastrous for the Fall River owners. But they had a bigger threat than some lost profits: the militancy of the women. So even though they raised the wages back and gave up the campaign to destroy the competition, they decided to lockout both the male and female workers to starve them into submission.

Hunger was an effective tactic. It was real. Fall River was close to a company town and the workers were literally starving. But none could work until the signed away their union membership. Enough did so by September 27 that the mills reopened. But the workers had one more act of resistance: a bread riot. Hundreds of workers, both men and women, marched through the streets of Fall River, carrying signs that read “15,000 white slaves for auction” and carried poles with loaves of bread impaled upon them. One woman beat the mayor over the head with a loaf of bread.

For these workers from Lancashire, the bread riot had a well-established past. It was a known act of resistance. For the American political establishment, employers, and the media, they had no idea what this meant, except for some conservative newspaper editors who realized this was meant as a revolutionary statement. The food riot also disturbed the native-born and French-Canadian workers, for whom this seemed too radical an scary.

In the aftermath, the spinners’ union went underground, the weavers’ union disappeared, and more moderate male voices retook control over the local labor movement. Many leaders of the strike were blacklisted, forced to either work in some other field for a pittance or move away from their families and friends to work in a mill.

I borrowed from Mary H. Blewett, “Manhood and the Market: The Politics of Gender and Class among the Textile Workers of Fall River, Massachusetts, 1870-1880,” in Ava Baron, ed., Work Engendered: Toward a New History of American Labor, published in 1991, for most of this post. For the material on British unions encouraging migration, I consulted Charlotte Erickson’s 1949 article “The Encouragement of Emigration by British Trade Unions, 1850-1900,” published in Population Studies.

This is the 331st post in this series. Previous posts are archived here.