This Day in Labor History: September 1, 1849

On September 1, 1849, the Brotherhood of the Union, an early pro-worker organization, formed. The vision of a radical named George Lippard, this organization established principles in American working class activism that would be incredibly influential throughout the 19th century, especially within the Knights of Labor, of which it is a direct predecessor.

Lippard grew up in Philadelphia, the son of once prosperous German farming parents somewhat lessened because his father was hurt in a farming accident. He grew up pretty rebellious and wild, especially after his father died. He thought about going into the ministry and studied for the law, but neither took. He decided to live like a hobo for awhile, sleeping in the streets, working odd jobs, and hanging out with the poorest white Americans in Philadelphia, mostly. He got to know Edgar Allan Poe in these years. Living this way, he experienced the true impact of the Panic of 1837 firsthand. For the burgeoning American working classes, at a time when the nation had not yet fully committed to industrial capitalism but was clearly heading in that direction, the Panic was the first sign of how this system would treat workers and how workers might resist this.

Ending his time slumming, Lippard began to write for local newspapers to tell the workers’ point of view. He also wrote a bunch of fiction. Much of it was historical romances, but in 1845, he published a novel called The Quaker City, or The Monks of Monk Hall. This was an explicitly anti-capitalist novel intended to call out the Philadelphia elites for their hypocrisy and indifference to the suffering of the poor. The novel consists of a variety of characters that prey on the working poor and thus threaten the very future of the republic. This became the nation’s best-selling novel until Harriet Beecher Stowe published Uncle Tom’s Cabin in 1852. It spoke to the growing frustration in the working classes over the poverty, corruption, and political indifference that hampered their lives. Now quite financially comfortable, Lippard then started his own newspaper, The Quaker City, to push his vision of working class emancipation.

Like many American reformers of this period, Lippard was not comfortable with European-style class conflict. Marx and Engels were starting to lay out their vision of communism and many other writers were articulating ideas around socialism. This scared many Americans. For someone like Lippard, the goal was to alleviate poverty and solve the problems that disempowered working people before that became necessary. Lippard then, again like many reformers, thought that employers and employees had mutual interests that should naturally coexist and that this mutuality should be encouraged. In this, he was not unlike later generations of reformers still struggling with the impact of capitalism, such as Edward Bellamy. To promote this vision, Lippard founded The Brotherhood of the Union on September 1, 1849.

The Brotherhood soon had 20 chapters around the nation. It took its inspiration as “the principle of Brotherly Love in the Gospel of Nazareth, and the affirmation of the Right of Man to life, liberty, land, and home in the Declaration of Independence.” The idea was to keep it pretty apolitical and then appeal to the broad artisan classes in the country’s cities. At first, he tried to ally with other social movements, including one early 1850s effort to guarantee everyone a homestead if they wanted one, but by 1852 or so, he believed that his organization was the only path to saving the nation from destruction. The organization itself was full of the symbolism so common in 19th century organizations, from the Masons to the Ku Klux Klan to the Knights of Labor, including insignia, rituals, and complicated levels of engagement that could lead someone to rise into leadership.

The various chapters did all sorts of things, vaguely related to republicanism, but not always about the working-class exactly. Some of them sent volunteers to help free Cuba from Spanish colonialism in the early 1850s, for example. It attracted a lot of land reform advocates as well. Some chapters welcomed black members. Lippard attacked the anti-Catholicism that divided the working classes, though this sentiment was certainly not shared by all the leaders of this organization. He also criticized acting in the political realm, especially the Democratic Party that already dominated many cities, but does not seem to have criticized chapters that did engage closely with one or the other of the major political parties.

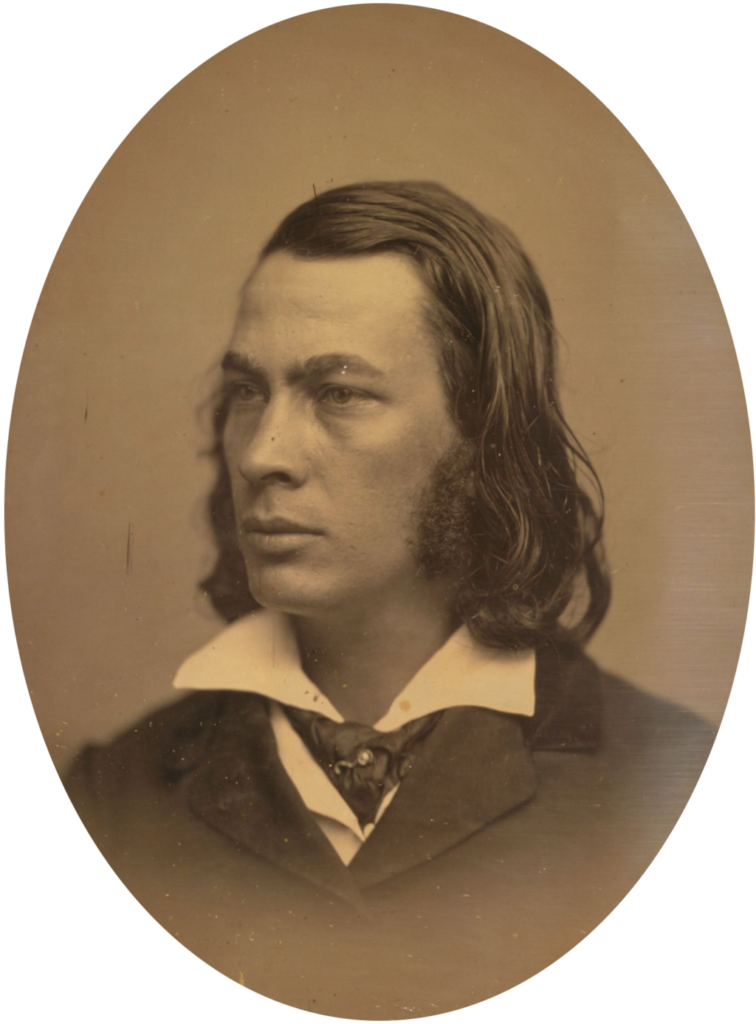

Lippard, who looks like a movie star, died in 1854, only 32 years old, possibly of pneumonia. What is significant about The Brotherhood of the Union is that it survived his death and became a sort of catch-all organization for concerned artisans that remained semi-relevant until the rise of the Knights of Labor, which, as referenced above, took a lot of the rituals and organizational principles and vision of mutuality from the Brotherhood. By the Civil War, the remnants of the group was identified mostly with the needle trades and created forms of working together that included people later involved with the founding of the Knights.

This post borrowed from Mark A. Lause, A Secret Society History of the Civil War, from 2011. For those of you would who like to read more about Lippard’s vision, more in his writings than the Brotherhood itself, check out Michael Denning’s book from 1987, Mechanic Accents: Dime Novels and Working-Class Culture in America.

This is the 327th post in this series. Previous posts are archived here.