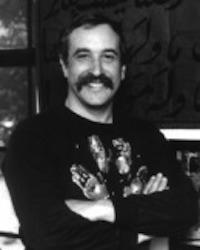

Ellis Goldberg, Remembered

The following is a guest post by Talal Hattar on the passing of Dr. Ellis Goldberg, University of Washington Professor of Political Science. While I did not work personally with Ellis, a great many friends of LGM did.

On the evening of Friday, September 20, my teacher, Ellis Goldberg, died. I cannot fully express the depth my sorrow. He is survived by three children and many, many friends, and I was not one of his better students. That said, he meant the world to me and his son, Shaul, has encouraged me to write. Therefore, I will say what is in my heart and pray that I not presume.

Steve Hanson, one of my other teachers here at the UW once said, “Oh, Ellis knows everything!” Steve is not given to hyperbole or effusive compliments and I can assure you that when it came to Ellis Goldberg’s vast erudtion, Steve was right. No man can know everything, obviously, but Ellis knew so much from any comparative vantage point he might as well have! He certainly knew more than anyone that I ever met or am likely to in this lifetime.

Ellis was a voracious reader. His knowledge of modern history was cross-continental and encyclopedic. There are many scholars of the Middle East who dislike theory and Ellis was one of them. I have always felt many of these scholars disliked theory because of the labor entailed in learning it. Ellis, in contrast, knew it all cold, every shred. While he thought little of theory, I got more clever insights into theory from him than I did from many who have actual passion for it.

Ellis’s passion was for empirical reality. He often argued that we don’t really know enough to about the empirical world to begin to theorize, especially in the Middle East. It took me years to understand this. Because of his teaching, I came to discover that many comparativist political scientists know their subject at a distance, using a medium-depth knowledge of their research countries to back some half-baked theory of limited generalizability. Ellis was quite good at stripping away my illusions.

I came to realize that many comparativists only have a partial grip on their research languages, especially when that language is Arabic. In contrast, Ellis read Arabic at a startling speed, far faster than any non-native Arabic speaker that I’ve ever met. He tracked the news in Arabic on a daily basis. His observations were always grounded in a deep comprehension of the local reality in which people lived. I certainly doubt any American scholar knew Egypt better.

His knowledge was the least of his gifts. Ellis was remarkable among all the scholars I have met in being utterly free from the taint of vanity. His curiosity was wholesome and completely genuine. He learned only from of a deep desire to know, not a need to impress or control. Truly he was a miracle. I remember that Ellis once told me that, in his years of studying politics, he had a great deal of trouble understanding why so many people relished power and privilege. For a man who was so good at exposing my own naïveté, he certainly startled me. The older I get, the more I wish I shared that blind spot. I truly believe that the reason Ellis did not understand that desire was because it was not in his nature to take pleasure in power and prestige. I would that my own heart were so pure.

The hardest lesson that Ellis taught me was in my role as teacher. When the time came for me to teach Arab-Israeli Conflict, he was brutally frank with me. He said, “You’re intelligent and angry. You can be intelligent OR angry and debate can continue, but intelligent AND angry will shut down all possible dialogue every time. People don’t stop asking the wrong questions when you leave the room just because they don’t dare ask them to your face. As this class is going to be your bread and butter, you have to figure this out.” It was very hard to hear, but I went on to teach Arab-Israeli six times as an instructor drawing on that advice and I have to count it as the finest teaching of my life. I don’t know if I shall every do something so beautiful in my work life again. I am grateful for his wisdom.

Ellis was compassionate and just. Academics live in an insular world that is rigidly defined by their career progress. Ellis alone taught me that it was a bubble. He believed in me during my years trying to make things work in the bubble, when I think very few people would have. When my bubble finally popped, his kindness and groundedness in real life were instrumental in weathering the rather hard psychological experience. I had taken it too seriously. Ellis had a genuine gift for living. His passing has reminded me very clearly that this skill is one that I have yet to learn to emulate well. Even in his death, he teaches me. I think as I enter last third of my life, I should make it my business to truly live this last lesson he has bequeathed me.

I love you, Ellis! I know you didn’t believe in an afterlife. That said, I hope that there is one, because if I learn to live as well as you taught me, I shall have the privilege of going there and seeing you again. I wish you peace.