Don’t Overthink It

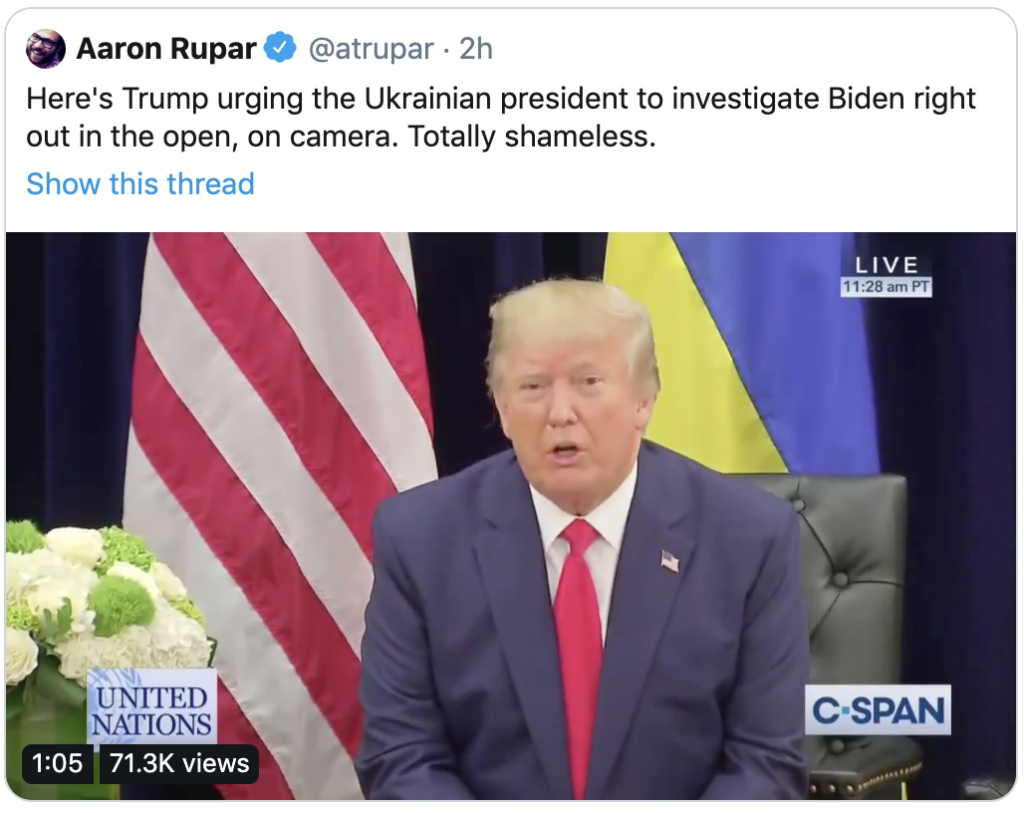

The summary of the Trump’s phone call with Zelensky, as Paul argues, provides very strong evidence of corruption. Although likely only a partial account of what transpired in that single conversation, it implies that the President of the United States used economic and military assistance as leverage in his efforts to convince the Ukrainian government to produce damaging information against his political rivals.

There is, of course, the point where Zelensky mentions that Ukraine would like to purchase additional Javelin anti-tank missiles, and Trump (apparently) pivots to asking Zelensky to assist Barr in getting dirt on the DNC. He later asks Zelenksy to have his people coordinate with Giuliani in going after Biden.

This is bad enough in the absence of the obvious context. In context, it’s much worse. Trump had recently ordered a halt to a $400 million aid package to Ukraine.

“Administration officials were instructed to tell lawmakers that the delays were part of an “interagency process” but to give them no additional information — a pattern that continued for nearly two months, until the White House released the funds on the night of Sept. 11.

During the intervening period, the Trump administration made repeated noises about drawing down U.S. assistance to Ukraine, often in the context of the patently absurd argument that the Europeans aren’t pulling their weight. Indeed, in May I conducted interviews in Brussels on the history of the 2014-2015 Ukraine crisis, where I got to hear a lot about the extensive EU support for Ukraine.

It was already pretty clear that noises about the EU and generalized concern over corruption were pretexts. Even McConnell was stymied in his efforts to find out why the Trump administration was holding up assistance.

All of this reflects only a limited slice of the context provided by the public record, let alone what we don’t know about. What, for example, did Giuliani say in his meetings with Ukrainian officials? We know that he pressured them to produce compromising material, because he’s admitted as much. Were there other contacts that reaffirmed Trump’s message? Presumably, the whistleblower had access to intercepts or other intelligence material that provides further evidence of malfeasance. What, for that matter, will the Trump administration redact in its supposedly impending public disclosure of the whistleblower report?

Paul invokes Arendt to describe how Republicans are attempting to spin the damning evidence already before the public. There’s very little difference here than in their approach to the Mueller Report, which provided ample grounds for impeachment and removal. Those efforts, with an assist from the Attorney General, seem to have worked. So it’s an entirely rational, if dispiriting, strategy.

When it comes to the assertion of a lack of a quid pro quo, Henry Farrell makes the obvious—but still worthwhile, especially coming from Henry—comparison to how mobsters generate legal plausible deniability around their criminal conduct.

Trump’s former lawyer, Michael Cohen has said President Trump “doesn’t give orders. He speaks in code. And I understand that code.” That’s the way that mafiosi speak to each other, in order to avoid trouble. In my book on the political economy of trust, I discuss the oblique ways in which Sicilian Mafiosi communicate with one another and how this affects trust and distrust among them, building on the work of sociologists such as Diego Gambetta.

Popular culture shows how mobsters communicate in code when they are worried about being overheard by law enforcement, using indirect language to describe their intentions, so as to make it harder to pin responsibility on them. Similarly, as Trump has said, he knew that his phone call with Ukraine was being listened to by intelligence officials, who would write up a permanent record of the call. We don’t know what Trump said – except that an intelligence official thought it worrying enough to take the risk of becoming a whistleblower. But we can reasonably guess that if Trump wanted to get Ukraine to hurt his presidential opponent, he did so using careful language that left no doubt what he wanted, but did so in a way that would preserve a minimal of deniability.

Sicilian mafiosi excel in using this kind of language. Loose-lipped Mafiosi risk giving valuable information away to the cops, or to fellow criminals who may not have their best interests at heart. The result, as the famous Mafia turncoat Tommaso Buscetta describes it, is that Mafiosi communicate with one another about their crimes in code: “Within the mafia, no-one will give you a blow-by-blow account of a crime; it is enough, and one should never ask more, that a person makes it clear, even through his silence [that he was] the author of a certain crime. … With us, a gesture, a look, a wink of the eye is enough to understand exactly what happened.”

I think that’s right, but all this analysis obscures two things.

First, only political expediency or strong cognitive bias could lead a reasonable individual to conclude that the known facts don’t substantiate corrupt purpose.

Second, the GOP repeatedly invokes the “court of law” frame to defend Trump. Mobsters sometimes get away with speaking in code because they confront a legal system that requires guilt beyond a reasonable doubt. But we’re not talking about criminal law. We’re talking about the fitness of the chief executive officer in a constitutional republic.

All the Republican obfuscation in the world can’t paper over the fact that, even in the illumination of the gaslight, Trump’s behavior has repeatedly marked him as a clear-and-present danger to the constitutional order and the rule of law.